Reasoning against Faith: When Clerics Intervene in Popular Religion

In their recent book The Enigma of Reason (2017), Mercier and Sperber debunk the popular view of reason as a source of disinterested, accurate knowledge about the world. The function of reason, they argue, is polemical rather than hermeneutic, as we mostly produce reasons to justify our actions to others and to evaluate the arguments other people use to convince us. This provocative argument opens up interesting avenues for further ethnographic investigations that would flesh out how argumentative reasoning functions across different cultural and socio-historical settings. As an anthropologist of religion, I find the question of how reasoning interacts with belief in the religious context particularly intriguing.

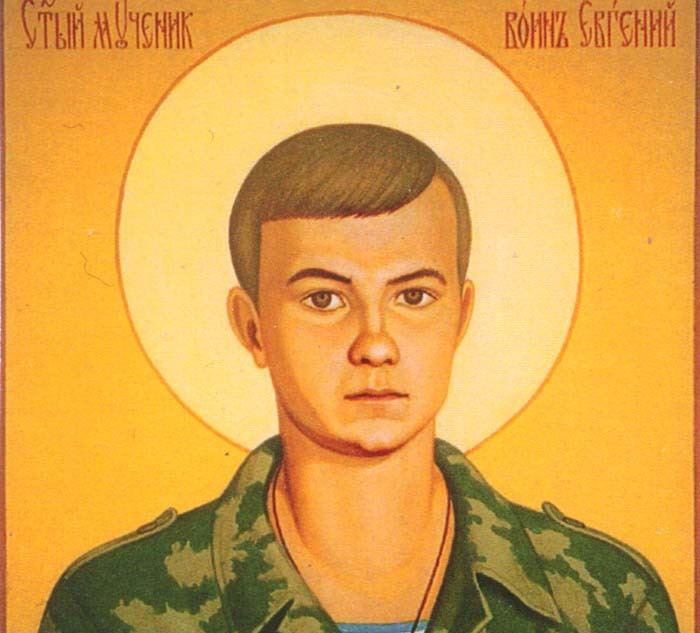

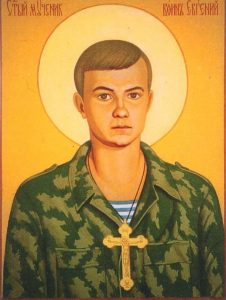

What role does reasoning play in communities that have an epistemic regime different from the secular post-enlightenment culture that formally privileges reason over other forms of cognition? And how and when do arguments succeed or fail at challenging religious beliefs and practices? These questions first crossed my mind as I was researching the popular but contested cult of a new martyr – soldier Evgenii Rodionov – in Russia.

Rodionov, a nineteen-year-old army private, was taken prisoner and beheaded in Chechnya in 1996, allegedly for his refusal to take off his cross and convert to Islam. He is embraced by many Russians as a national hero and popularly venerated as a martyr by some Orthodox believers. However, despite public pressure and Rodionov’s fast growing popularity, the Russian Orthodox Church’s Synodal Commission for the Canonization of Saints refused to canonize him upon reviewing his case in 2004. The major reasons for their decision were the lack of evidence that Rodionov was an observant believer and the impossibility of verifying the circumstances of his death (Maksimov 2004). As I was exploring the positions of Evgenii’s venerators and those of the Church representatives, I noticed that the two groups employed very different discursive strategies for the legitimization of their respective beliefs.

The skeptical clergymen often proceeded to list the reasons as to why the fact of Rodionov’s sainthood could not be firmly established. They also focused a great deal on condemning the practice of producing icons of the soldier and venerating him without the Church’s authorization. As the representative of the Commission for Canonization, Maksim Maksimov (2004) put it,

Canonization is not giving away awards to everyone who has suffered. Canonization – is a call of the Church to turn one’s heart to someone who believed in Christ and preserved this faith until the end. When studying the life and death of Evgenii Rodionov, we have a right to request certain evidence that it indeed happened this way. However, it turned out that the main sources in this case … are the mass media. … There is no evidence that Evgenii … led a conscious churchly life and no evidence proving martyrical – in the churchly sense of this word – death was found by the Synodal Commission for Canonization. Therefore, any talk about the glorification of Evgenii as a saint is inappropriate and unjustifiable.

By contrast, almost all of Rodionov’s venerators that I interviewed – most of whom were lay believers – struggled to coherently explain why they believed in the soldier’s sainthood. They did not have much interest in debating whether Rodionov fit the Churchly criteria of sainthood [1] and instead claimed to just “know” or “feel” that the young men was a saint. Unlike the Churchly authorities, who asked for evidence of the truthfulness of the soldier’s story, many believers approached it as a matter of faith instead. As one young pilgrim whom I met by Evgenii’s grave put it, “For me it is obvious that Evgenii is a saint. There will always be people who ask for proof, but my response to them is why don’t they ask for proof of Jesus’s holiness? None of them have met Jesus during their lifetime – it is a matter of faith, and it is the same with Evgenii.”

Such a dynamic, I argue, is representative of the way reasoning functions in the Orthodox Christian tradition that habitually privileges spirituality and affective experiences over other forms of cognition. The apophatic Orthodox theology postulates the impossibility of cognizing God or divine mysteries rationally. Instead, believers are encouraged to consolidate their faith through participation in rituals and the pursuit of mystical experiences that bring them closer to God (Naumescu 2018). Anthropological research on religious transmission in Orthodox Christianity highlights the central role sensory experiences and bodily practices play in the process of both bringing about the experience construed as “spiritual” by its practitioners and reinforcing people’s commitment to faith (Boylston 2013; Luehrmann 2018). While Orthodox Christianity has a rich theological tradition in which reasoning and argumentation play a central role, the theological knowledge most lay believers possess is rather fragmented and they often defer to the authority of tradition and expert opinions of the priests when it comes to doctrinal matters (Bandak and Boylston 2014).

Such an epistemic regime that explicitly positions the sacred mysteries beyond the reach of reasoning proves instrumental in securing the transmission of faith in the context of encroaching secularism and the attacks of skeptics. However, it also poses a challenge to the institutional authority of the Church whose monopoly over the interpretation of the religious tradition can be challenged by schismatics and charismatic visionaries. Taught to rely on their intuitions and feelings and often lacking a deep knowledge of Church tradition, believers are easily drawn to beliefs and ritualistic practices not sanctioned by the Church – a phenomenon known as “popular” or “folk” religion. It is precisely in this context of tensions between the doctrinal and popular practices that reason-based arguments, otherwise downplayed in Orthodox religious pedagogy, come to the fore. Drawing on their authoritative knowledge of theology, priests come up with elaborate arguments to denounce and discredit the persisting non-canonical practices, like for instance the veneration of an uncanonized soldier.

The case of Orthodox Christianity seems to nicely dovetail with the argument advanced by Mercier and Sperber, as it demonstrates that even a tradition that generally does not rely on reason for the formation and transmission of its core beliefs still makes active use of argumentative reasoning to maintain the hegemony of the Church as an institution over the sanctioning of beliefs and practices. The strategy of appealing to reason, however, is only successful in some cases. For instance, the arguments brought by the Church against the canonization of Rodionov failed to convince his venerators, who dismissed the Commission’s decision as politically-motivated, suggesting it was guided by fear of further exacerbating Christian-Muslim tensions in Russia. The calls upon the Church to revise the soldier’s case persist and many among Rodionov’s venerators are convinced that his eventual recognition is imminent. Such a scenario is indeed plausible, given that the large-scale popular veneration of a person (especially when combined with the testimonies about his/ her miracles) can itself serve as a ground for canonization in Orthodox tradition. When reason fails to successfully curtail the uncanonical beliefs and practices, the latter can eventually come to be incorporated into the tradition thus expanding its repertoire of authorized practices.

References

Bandak, Andreas and Boylston, Tom. 2014. “The ‘Orthodoxy’ of Orthodoxy: On Moral Imperfection, Correctness, and Deferral in Religious Worlds.” Religion and Society 5 (1): 5-46.

Boylston, Tom. 2013. “Food, Life, and Material Religion in Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity”. Pp. 257-274 in A Companion to the Anthropology of Religion edited by J. Boddy and M. Lambek. London: Wiley Blackwell.

Luehrmann, Sonja, eds. Praying with the Senses. Contemporary Orthodox Christian Spirituality in Practice. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Maksimov, Maksim. 2004. “Mozhmo li Speshit’ s Kanonizatsiiei?” Tserkovnyi Vestnik 1-2: 278-279.

Naumescu, Vlad. 2018. “Becoming Orthodox. The Mystery and Mastery of a Christian Tradition.” Pp. 29-53 in Praying with the Senses. Contemporary Orthodox Christian Spirituality in Practice edited by S. Luehrmann. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

***

[1] A number of clergymen supporting the soldier’s case did, however, engage in polemic with their colleagues, arguing that few of the saints venerated by the Russian Orthodox Church would meet the canonization criteria put forth by the Church today.

No comments yet