Do chimpanzees really care about equity?

One of the most popular Youtube videos in comparative psychology features capuchins exchanging tokens for food with a human experimenter. It is fascinating to see how outraged the capuchin becomes when realizing that the experimenter is giving her cucumber while she is giving out grapes (much more tasty food) to another capuchin! After watching this video [1], it is hard not to jump to the conclusion that capuchins, just like humans, are inequity averse. And yet many studies have casted doubts on this conclusion (here is a short review I wrote about this topic for ICCI back in 2009). For a start, why would capuchins (and chimpanzees and dogs) have a sense of fairness given how small (or null) the place of cooperation plays in their ecology?

In a new study just published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Jan Engelmann and his colleagues from Michael Tomasello’s lab at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig put forward a novel hypothesis—the social disappointment hypothesis—according to which food refusals express chimpanzees’ disappointment in the human experimenter for not rewarding them as well as they could have.

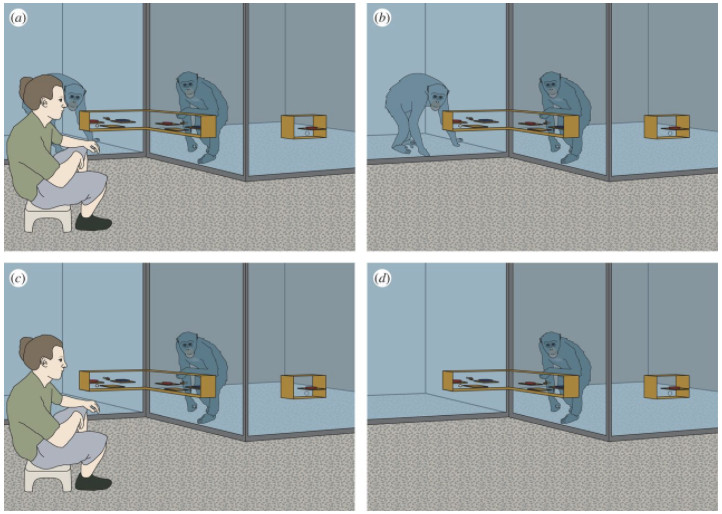

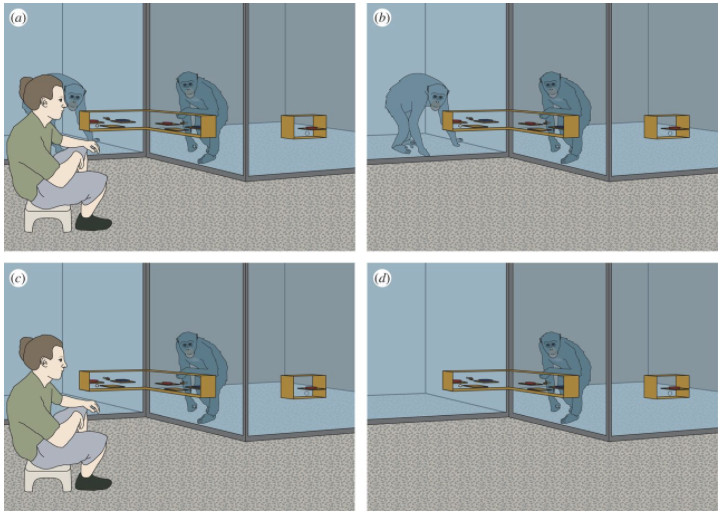

They tested this hypothesis in a new design in which food was either distributed by an experimenter or by a machine and with a partner that was either present or absent (see picture).

They found that chimpanzees are more likely to reject food when it is distributed by an experimenter than by a machine and that they are not more likely to do so when a partner is present. In other words, what looks like moral outrage is actually social disappointment.

A great methodological lesson, and an important study for the understanding of the evolution of human cooperation.

[1] “Capuchin monkey fairness experiment” (video). Source: Youtube @vladimerk1. April 13, 2012.

6 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Dan Sperber 2 September 2017 (19:28)

Expression of emotion?

With its “two-by-two design in which food was either distributed by an experimenter or a machine and with a partner present or absent,” Jan Engelmann et al.’s article provides, as stressed by Nicolas, strong evidence against the claim that Chimpanzees’ and other animals’ refusal of a lesser quality come from equity aversion. It provides equally strong evidence against the view that this behaviour comes from a frustrated expectation that they would get higher quality food than what they are actually getting. Subjects’ expectation was not just that they would get the higher quality food, but that the agent with whom they were interacting would provide it. Their disappointment is not so much about food as it is about social interaction.

I find the argument quite convincing – and I am not too surprised that no comment has yet been offered in defence of the equity aversion thesis – but it raises an interesting question (among others) on chimpanzee communication.

The idea seems to be that chimpanzees not only experience this social emotion, but also that they express it, i.e. communicate about it. To do so, chimpanzees should have the ability not only to give behavioural evidence of their emotion but also to interpret this evidence in the behaviour of others. Shouldn’t they also tend to respond in a way that makes this expression of emotion advantageous? Is this what is being claimed, and if not, what is? Is there any evidence beyond this very study in support of the three part of the claim (as I understand it): a specific form of expression; the ability to recognize it in others; the producing and the recognizing of this communicative behaviour being adaptive?

Guillaume Dezecache 2 September 2017 (21:09)

Fairness in the ecology of non-human primates

Thanks Nicolas and Dan for pointing out this very interesting study!

Upon reading it, I was not clear why the machine vs. human comparison was relevant at all. Captive chimpanzees commonly interact with people and they probably have learnt that they can change the behaviour of animate vs. inanimate objects, or that of humans vs. other kinds. In that sense, it is strange to expect chimpanzees to react similarly to a machine than to a human. Jan and colleagues discussed this issue at the end of the paper, and they seem to suggest that, since they did not observe any clear begging behaviour nor protest from the chimpanzees, the subjects clearly did not look for altering the behaviour of the experimenter. This is not so convincing: captive chimps in Leipzig probably (note: I am not sure that it is the case, I am happy to receive clarifications from Jan or others) face situations where they respond wrongly to an experimental solicitation, and they probably just wait for another opportunity. This predicts that they would start protesting only on the last experimental trials (when they understand they are being tricked all the time).

Additionally, I would have expected a similar experiment with human children. Human children would probably have treated the machine vs. the human differently. They would have been ok with a machine treating them unfairly, but would probably have received an unfair treatement from humans. If my prediction is correct, I doubt the social disappointment hypothesis would have been proposed at all!

The critical test seems to be the absence vs. presence of partner. Clearly, this goes against the results of de Waal and others.

More largely, I think Nicolas raises an important theoretical issue: why should apes and monkeys show fairness in their ecology? This is an open question. As a wild chimpanzee researcher, I may foresee potential situations where fairness (or the ability to compute social comparison between one’s situations and others’ and to use those comparisons) could be present in chimpanzees I guess that this is the next avenue: put on your gum boots, go to see the animals in the wild, and try to delineate situations where this is needed.

The same goes for the feeling and expression of disappointment: are there situations in the ecology of chimpanzees that may trigger it? Otherwise, it might just be an artifact from a laboratory study (which is interesting enough).

Jan Engelmann 3 September 2017 (14:50)

The emotion of social disappointment (reply to Dan)

Dear Dan, thanks a lot for forcing me to be clearer and more specific about the emotion of social disappointment.

In fact, when we had first brainstormed about this paper, we had given the emotion the name ‘social anger’ instead of ‘social disappointment’. We had opted for this term given that the famous response of the capuchin monkey in the Brosnan and de Waal study (see Nicolas’ post) seemed indicative of anger towards the experimenter. However, in our study we found active forms of protest (e.g. throwing the tool at the experimenter) to be very rare, and more passive forms (e.g. dropping the tool on the ground and moving to a corner of the room) to be very frequent. Given our data, we changed the name of the hypothesis from ‘social anger’ to ‘social disappointment’.

Now, if we had observed more active forms of protest, i.e. social anger, their communicative function would have been very straightforward, I would think. For example, Leda Cosmides, John Tooby, and colleagues have recently developed a convincing theory of the evolutionary function of anger (see, for example, Sell et al: “The grammar of anger” in Cognition). According to their theory, my anger towards you is triggered by an indication that you place too little weight on my welfare. I communicate this to you – potentially by displaying the prototypical anger facial expression – to let you know that you should ‘do more of what I want or I will do less of what you want’ (p. 111 in Sell et al). We certainly are very good at recognizing anger in others. Depending on whether we value our relationship to the person we have wronged or not, we might then engage in behaviors to repair our relationship. So I would think that displaying anger and recognizing it in others is obviously adaptive.

Can the same be said about the emotion of social disappointment? Is social disappointment communicative in this way too? I think so. It is important to note that the social disappointment of chimpanzees observed in our study is certainly costly: they give up food that they otherwise happily eat (see our food preference test). In fact, the experience of this emotion leads chimpanzees to terminate a cooperative exchange with the human experimenter (the experimenter in this study gives food to the chimpanzee in order to get the tool, just like in the Brosnan and de Waal study). Anecdotally, this sort of behavior has been observed in the wild as well (among chimpanzee dyads). If chimpanzees feel that they are not treated well by their friends, they might do such things as fail to respond to their friend’s request to groom them or fail to respond to their friend’s plea to support them in a fight. Now, to the interpretation of this behavior: I would think that – similar to the emotion of anger – social disappointment signals to the partner that I am not happy with how she is treating me. It might even signal a willingness to switch partner. As Mike Tomasello puts it in the context of partner choice: “if you do not shape up I will ship out” (A Natural History of Human Morality, page 52). This also would explain why the ability to recognize this emotion in others would be adaptive: it can motivate action to minimize the risk of losing valued partners. Of course, this is all very speculative. But I hope that we and others can test these predictions in future studies.

What I am unsure about: when do chimpanzees (and we) display disappointment rather than anger? We all know situations, maybe particularly from close social relationships, where we retreat to our room in disappointment rather than directly confront a valued partner with anger.

Jan Engelmann 3 September 2017 (15:37)

Reply to Guillaume

Dear Guillaume, thanks a lot for your comment and for highlighting some crucial issues concerning our study.

The machine-human comparison is crucial. Thanks to this comparison we can show that chimpanzees’ protest is grounded in a SOCIAL expectation and not simply in a (for example) statistical expectation to receive the high-quality food. If a non-social expectation to receive the high-quality food motivates chimpanzees’ protest in the inequity aversion task (as some have argued), we should find equal refusal rates in both the human and the machine condition. However, we do not. Chimpanzees hardly ever refused the low-quality food from the machine – they only did so in about 2% of all trials with the machine, compared to 26% in human trials. However, you raise an alternative interpretation (which we also address in the paper). Maybe chimpanzees did not have any expectations towards the experimenter. Rather, upon receiving the low-quality food, they protested against the experimenter because they thought that they could change his behavior, but not against the machine because they didn’t think they could change the machine’s behavior. I doubt that this reductionist account can explain chimpanzees’ behavior. Chimpanzees in Leipzig behave in a very predictable way when they want a certain piece of food: they beg for it. However, we did not observe a single case of begging in the current study.

Regarding children’s behavior in a similar setup. I think you leave out a crucial point. Children, from around the age of 3 onwards, would probably also have protested more in the partner present compared to the partner absent condition (see paper by McAuliffe et al “Social influences on inequity aversion in children”). That is, children from this age onwards show evidence for fairness based on social comparison. However, and this is a hypothesis I would like to test in the future, maybe children’s reactions to unfair divisions before this age would be more similar to chimpanzees’ reactions in the current study.

I fully agree with your final point. It is not clear how and whether chimpanzees’ social ecology selects for fairness. On the other hand, it is quite clear to me why chimpanzees’ would develop special expectations towards social partners and concurrent reactions of social disappointment. After all, experimental and observational evidence suggests that chimpanzee cooperation is mostly regulated through so-called emotional bookkeeping in dyadic social bonds.

Dan Sperber 5 September 2017 (09:13)

Do chimpanzee sulk?

In response to my earlier comment, Jan writes:

Very interesting. So the emotion of “social disappointment” as Jan describes it has a function similar to that of anger, but an emotional tenor quite different from it. Its behavioural expression is quite different too: withdrawal – in fact what in humans we describe as “sulking” – rather than aggression. A hypothesis that come to mind is that it has to do with hierarchical relationships: a dominating agent (or one trying to dominate or, at least, to refuse to be dominate) might resort to anger. A dominated agent, on the other hand, might pay to big a price for anger but may convey a low-key threat to terminate a relationship or at least be much less involved in it by such withdrawal behaviour.

Jan, what observational or experimental evidence is there that chimpanzees (and other non-human primates) sulk?

Jan Engelmann 6 September 2017 (19:01)

No studies on sulking in chimpanzees

I just checked and we have some evidence for your proposal, Dan. The few instances of active protest that we observed in our study (what looked more like anger) all came from higher-ranking chimpanzees. Low-ranking chimpanzees, on the other hand, only showed disappointment.

Unfortunately so far there is not a single study – experimental or observational – that looks at sulking in chimpanzees.

In a current study relevant to this topic, we investigate whether chimpanzees do not not only preferentially help and trust their friends (as we have shown in previous studies), but also form special expectations towards their friends. Do they have a stronger expectation that their friend will help them compared to a neutral peer?

Another interesting study would be to re-run the current experiment, but this time with an interaction between two chimpanzees. Do chimpanzees react stronger emotionally if a friend compared to a neutral individual consistently gives them the non-preferred food? And does their emotional reaction (anger versus disappointment) vary as a function of their relative dominance toward the partner?