The R-word: “Racism” across the political spectrum

As a professional cognitive scientist, I usually conduct experiments on other people. However I recently carried out a somewhat unique experiment on myself. In this, I switched the political orientation of my on-line identity, in essence becoming a social media Republican for two weeks. In practice this meant two things. First, I altered my information feeds in Twitter and Google News to provide news and opinions primarily from an American right-leaning political perspective. Secondly, I posted links on Facebook to what I considered to be the most interesting content I found from the right, though I did notify my friends of this beforehand so as not to totally confuse them. The goal was to make a good faith effort to seek out the best opinions that go against my own and really try to see things through the lens of my political opponents. In addition to posting links, I also defended the views taken from or inspired by the articles I posted (as I usually do for the normal things that I post). The hope in doing this was that in actively changing my perspective on ideas with which I vehemently disagree, I might gain some special insight into how probable Republican voters think and maybe even change my own mind about a few things.

Despite some initial skepticism from conservative friends, I found the experiment to be worthwhile, and it resulted in a number of insights that could be of interest to people across the political spectrum. I just want to concentrate on one of these here: how people use the term “racism.”

From a liberal perspective, it seems fairly obvious that Trump and many of his supporters from within and without the Republican party are racist. Certainly before I began my experiment, I believed this. Liberals are aware, for example, that in January of 2016, 20% of Trump supporters (at least those from the primaries) “disagreed with freeing the slaves”. We liberals generally agree that Trump’s proposal to put up a wall with Mexico and to ban all Muslims from entering the United States is racist. Liberal sites often talk about the “Southern Strategy” in which the Republicans, during and just after de-segregation, gained huge amounts of political support in the southeast by appealing to racism against African Americans.

Another example of “obvious” Republican racism came during my social media experiment when Donald Trump claimed that U.S. District Judge Gonzalo Curiel should be disqualified from overseeing the Trump University case because of his “Mexican Heritage”. To liberals and many conservatives, this is about a clear of an example of racism as you are ever going to find.

However, in one particularly heated debate on my Facebook wall between a liberal friend and a non-Trump supporting but conservative friend, it became apparent to me that many well-meaning and intelligent people on the right deny that racism is rampant within the Republican party. They will even go so far as to deny that Trump’s comments on Gonzalo Curiel were actually racist. During this lively exchange between my two friends, my experimental responsibility seemed to be to defend the position that Trump’s comments weren’t racist or as bad as the liberals would have us believe. But try as I might, I honestly couldn’t figure out how to do it, even after getting a lead from others. How could any reasonable and well-intentioned person deny what is blatantly obvious?

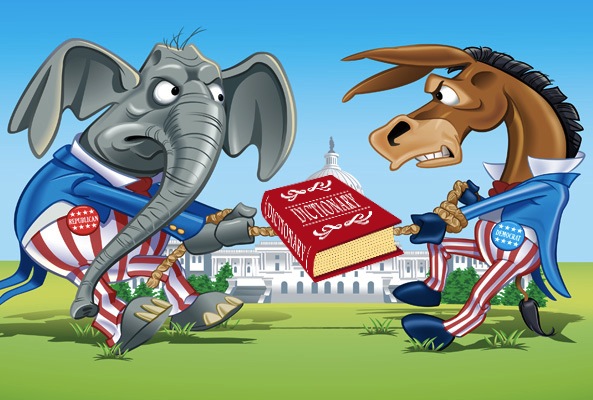

After observing a few conversations and talking with conservative acquaintances and friends, it became apparent to me that people from opposite sides of the political spectrum tend to use different definitions for the same word. While liberals are often willing to apply the term “racism” to forms of discrimination that do not obviously involve race such as discrimination on the basis of nationality or religion, people on the right tend to use a strict dictionary definition for the term.

When I Google “racism,” the first two definitions that come up are (1) “the belief that all members of each race possess characteristics, abilities, or qualities specific to that race, especially so as to distinguish it as inferior or superior to another race or races” and (2) “prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism directed against someone of a different race based on the belief that one’s own race is superior.” Both of these definitions would fail to count as racist many acts or attitudes that are regularly labeled as such by those on the left. For example, neither Trump’s proposal to build a wall between the US and Mexico nor his proposal to ban Muslims from entering the country would count as racist on these definitions. Neither proposal is based on the belief that all members of a relevant race possess qualities specific to that race which thereby make them inferior. Nor is either proposal obviously discrimination directed towards someone of a different race because of a belief that their race is inferior. Being Mexican is not a race, it is a nationality. Similarly being Muslim is not a race, it is a religion. Members of many different “races” (assuming you believe in such a thing at all) can be Mexican or Muslim. So, the Republican can argue, Trump’s proposals and attitudes don’t fit the dictionary definition of racism.

Here’s another example that came up with a conservative friend (for whom I generally have great intellectual respect despite not belonging to the same political “tribes”) during my experiment. In a recent survey it was found that “racial resentment” more strongly correlated with Trump support than a number of other factors such as age, education, income level, economic pessimism, or support for free trade. This is evidence that Trump supporters are, on average, more racist than the rest of the population, right? “No!” says the conservative. Racial resentment is not the same thing as thinking that a race is inferior, so this study doesn’t measure racism.

And even with regards to Trump’s statements about judge Curiel, some columnists have argued that these were not necessarily racist. These arguments are similar to those defending the idea of building a wall with Mexico from charges of racism. Curiel was being attacked for bias which might have been brought about from his Mexican cultural heritage, which is entirely separate from his race (read “skin color”). If Curiel had been black, white, or brown, Trump’s argument would not have changed. So, the argument goes, it is not appropriate to accuse him or his supporters of racism in this case.

Understanding the origins of definitional differences

These differences in definition and usage between the political left and the right are likely to be explainable by a mixture political pressures and well-known processes of language use. The rational nature of these could be related to other contexts in which, for example a (sometimes implicit) desire to ask a question while retaining plausible deniability may motivate indirect speech, as when a guy asks a girl “do you want to come up stairs to see my etchings” instead of just asking her to have sex [1]. Just as desires and constraints here may be leading people to adopt certain linguistic strategies, they may do the same in the case of the term “racism.”

What seems to be happening is the following: Across the political spectrum there is broad agreement that being called a racist is bad. This is a word that has a strong negative emotional charge that is universally recognized in our linguistic community. No one wants themselves or their group to be labeled as racist because of the huge reputational costs this incurs. There is also broad agreement that racism includes discrimination on the grounds of race. However, despite existing dictionary definitions, the precise working definition remains hazy and imprecise. For example, the naive concept of “race” employed by the general public is a shifty notion that has does not have a clear biological basis [2,3], and this lack of clarity in the term “race” likely carries over to “racism.”

For reasons like this, there is some built-in flexibility allowing us to extend meaning during language use. It is important to note that this process of meaning extension is entirely natural. It has been primarily studied by linguists interested in “polysemy” [4], who have pointed out that people extend meanings on a regular basis, as when we use the word “newspaper” to refer not only to a physical object with pages (e.g. “pass me that newspaper”), but also to refer to the content of a newspaper (e.g. “I read the newspaper on my ipad”) or even to refer to an entire organization (e.g. “The newspaper fired its editor).

However, political and social pressures create differences between sides in exactly how these natural processes of meaning extension play out. In American politics, Republicans and conservatives since the Nixon administration have consistently held positions that make them more vulnerable to accusations of racism (such as demanding voter ID’s, which disproportionately affects minorities’ abilities to vote). Modern day liberals on the other hand place a high value on social equality and see racism as one of the world’s great evils. Because of this dynamic, liberals seem to be inclined to extend the use of the term “racism” (and “racist”) to cover near semantic neighbors like discrimination based on ethnicity and religion, especially when these are perceived to correlate with skin color. Moreover, liberals note that the psychological mechanisms underlying discrimination (e.g. discrimination based on religion, sexual preference, and race) are very similar even if the objects of discrimination can differ. This makes it all the more natural for a liberal to extend the use of the term.

Where liberals’ interests are in extending the term, Republicans are incentivized to adopt strategies meant to defend against accusations of racism. A typical debate might start with a liberal saying “Trump’s remarks about Curiel were racist.” The conservative replies by saying “They weren’t racist at all.” The conservative can then force the liberal to consult the dictionary and win the argument on a technicality (though this may be putting the bar too high). It might be objected that this all suggests that liberals could simply win their arguments by using a more technically accurate term such as “bigot”, though this would be the prosecutorial equivalent of lessening the charges against the defendant as “racist” is likely perceived to be a more serious charge than “bigot” (as suggested in the NY Times article above and here.

The point here is not which side is wrong. It is instead to point out that this natural process of linguistic extension and restriction of meaning seems to be partly predictable on the basis of political pressures. A moment’s reflection suggests that there may be a more general rule at play. Whenever one (or one’s group) is vulnerable to accusations of possessing some quality broadly recognized as negative, then that person or group is likely to define/use the relevant term more in a more restricted way. However, when one’s opponents are vulnerable to accusations of possessing some quality broadly recognized as negative, then a person or group is likely to use the relevant term in a less restricted way.

The hypothesis that the meaning games being played out between Democrats and Republicans reflect more general processes would need to be empirically tested, but intuitively this strikes me as likely to be true. Democrats seem to use the terms “communist” and “socialist” more precisely than Republicans as Democrats are more vulnerable to charges of communism or socialism, both of which traditionally have a negative connotation in America. Similarly I bet that in Great Britain, the Tories and UKIP are defining the terms “xenophobic” and “nationalist” in a more restricted way than those on the left in UK politics.

[1] Pinker, S., Nowak, M. A., & Lee, J. J. (2008). The logic of indirect speech. Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences, 105(3), 833-838. [2] Lewontin, R. C. (1972). The apportionment of human diversity. In Evolutionary biology (pp. 381-398). Springer, New York, NY. [3] Pigliucci, M., & Kaplan, J. (2003). On the concept of biological race and its applicability to humans. Philosophy of Science, 70(5), 1161-1172. [4] Pustejovsky, J. (1998). The generative lexicon. MIT press.

9 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

cathalcom 27 August 2016 (12:30)

Very interesting, in addition it might be worth considering that not only is a general linguistic phenomenon explaining the political phenomenon, but that the particular political dynamic you’re talking about might explain some of the linguistic phenomenon. It doesn’t seem to appear at least in Blank’s (1999) account of the forces for semantic change. If I’m understanding the hypothesis, it predicts that within an in-group, negative terms that could be used to characterize an out-group will be broadened, and positive terms that characterize the out-group narrowed; conversely, positives that characterize the in-group broadened and the out-group narrowed. So, in Ancient Greece ‘alcoholic’ might be very narrow (“alcoholic?! He only drinks 4 nights a week!”), while in Sparta (or wherever) it might be applied more broadly (“total alcoholic – he has wine every Sunday”). And similarly for contemporary groups. So, this could explain patterns of semantic change behind ‘thick’ or morally loaded concepts (Blackburn 1998).

Blackburn, S. (1998) Ruling Passions, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Blank, Andreas (1999), “Why do new meanings occur? A cognitive typology of the motivations for lexical Semantic change”, in Blank, Andreas; Koch, Peter, Historical Semantics and Cognition, Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 61–90

Francois 28 August 2016 (22:02)

My first impression is that D. Trump is less racist and less agressive than H. Clinton. And this is not a matter of how to define the R-word.

Brent Strickland 28 August 2016 (22:42)

Certainly first impressions can vary from one person to the next. More generally though, I think people (including both politicians and non-politicians) on the right in the US are more often accused of racism and supporting racist policies than those on the left. This observation is of course independent of whether those accusations are well founded or accurate.

Brent Strickland 28 August 2016 (22:38)

@Cathal Thanks for these helpful comments. I’ll definitely check out those references which sound like they are arguing for exactly the type of sociolinguistic process which I suspect is at play here.

Thom Scott-Phillips 29 August 2016 (13:38)

Thank you Brent for the interesting post.

Funny timing. Just a few days ago I was listening to a BBC podcast about alt-right, the US political movement that has a great deal of overlap with support for Trump. One of the contributors made exactly the point about definitions that you make here. He talks about how “real” racists are geeks searching for biological differences, and that’s not what alt-right are about.

Have a listen from minute 17:30, here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07pjb9y (the relevant passage is around 90 seconds long, but the rest of the show is interesting too)

Brent Strickland 29 August 2016 (15:54)

Thanks Thom. This is indeed very relevant. The contributor from the segment, who I assume is more right than left leaning, made another remark in passing that I found interesting. After accepting that there is some racism (under a strict definition) in the alt-right movement, this was dismissed as being only true of an exceedingly small minority within the movement. It seems fairly likely to me that if you were to provide even a very specific definition of the word “racist” and then run an experiment asking people from the left and the right to judge the % of racists in their own political group and in their opposing political group, you would get higher estimates for the opposing groups (and I suspect the effect would be larger when lefties make the judgments than when righties do). Any such biases in numerical judgments and the motivated semantic expansion/contraction effects discussed in the main article would seem like two sides of the same coin. Both seem to come from an underlying motivation to smear one’s opponents and/or protect ones allies.

Thom Scott-Phillips 29 August 2016 (21:35)

Yes, that makes sense as a prediction. You could ask people to define the word racist too. I’d be interested to see the results.

Brent Strickland 29 August 2016 (22:31)

We’re just starting to run some studies along these lines at the Institut Jean Nicod. We’ll definitely keep you in the loop once we’ve got some clear results!

Brain molecule Marketing 18 November 2016 (16:20)

My understanding is that ethnic hatred is a primary biological driver of social behavior – fear of the outsider. Fear mongering about the outsider is the most universal and historically reliable strategy for political power and generating media consumption behaviors.

Since ethnic hatred is so fundamental and powerful, there was likely some evolutionary advantage – a long time ago for proto-human ancestors. the “Pathogen Stress Theory” looks at some correlational evidence for this. However, in modern humans, ethnic hatred correlates with lots of violence and destruction – not so adaptive anymore. Unless, you want votes and media consumption.

Biologically and medically, genetically, the models of “race” are complex and pretty undecided. For example, does ethnic background effect medical conditions? Well, yes and no…