- 'The Origins of Monsters' Book Club

The Speculative Origins of Monsters

A researcher in the field of cultural evolution - whom I never met in person and who would be probably very surprised of this wildly out-of-context mention - twitted, few weeks ago, that “Implementation is the hard part, not the idea. […] I have five ideas in the shower every morning. That's the easy part.” My showers are, alas, far from being that exciting, but, for some reason, the musing resonated with me when I first saw it, and it continued to resonate through the reading of The Origins of Monsters.

There is much to like in David Wengrow’s book. The Origins of Monsters inspects the diffusion of a very specific cultural item (first plus) making use of Dan Sperber’s epidemiology of representation (second plus), and exploring how both universal cognitive factors and local, socio-economical, ones contribute to the item's success (third plus).

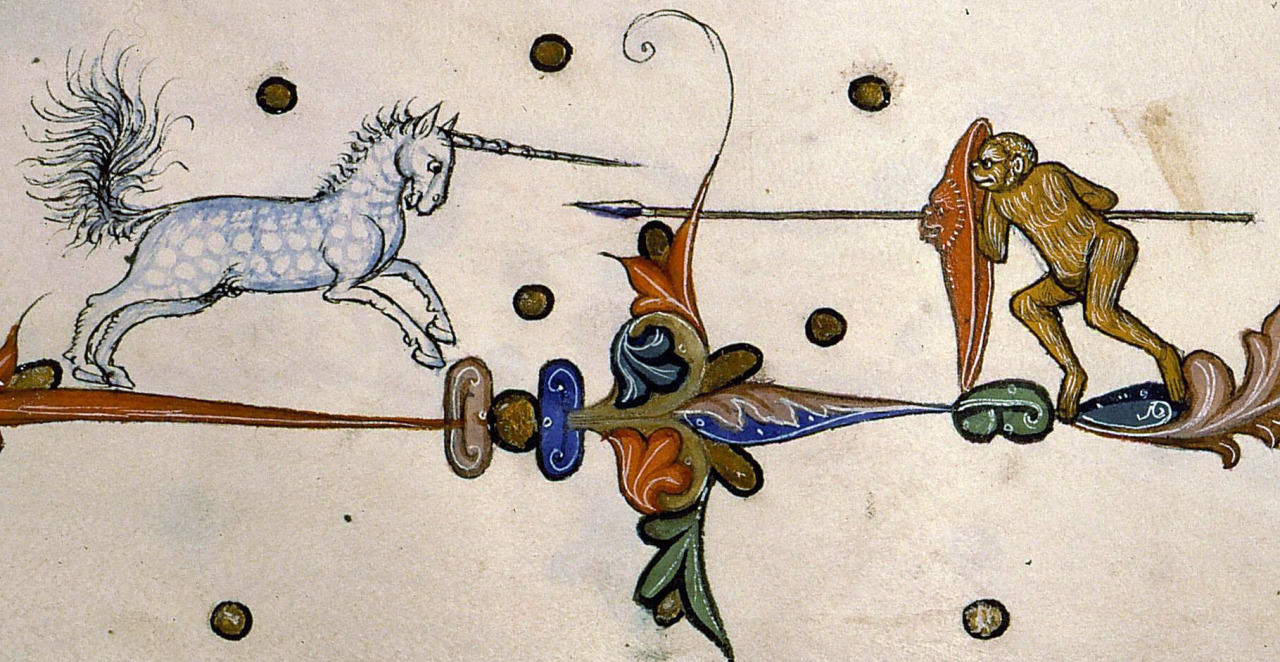

Let me unpack this sentence. Wengrow examines the reasons of the success of images of monsters, or, better, “composites”, i.e. images of fictional beings, composed using combinations of anatomical parts of real beings: the chimaera in the Greek mythology is a well-known example of such images. According to Sperber and other cognitive anthropologists, these composite figures explicitly violate our intuitive, domain-specific, expectations (lions do not usually have a snake as a tail) and, in the same time, conform to them (heads are where heads are supposed to be, etc., and composites are readily recognised as “living kinds”). It is this combination, in jargon the fact that they are minimally counter-intuitive (MCI), that makes supernatural beings in general, and composites in this particular case, cognitively appealing.

Wengrow endorses this hypothesis, but also notes that the distribution of such composites may follow a peculiar pattern in space and time, difficult to explain if "MCI" were the only reason of their success. Such images appear to become more common “in the first age of mechanical reproduction”, that is, with the emergence of the earliest urban societies, together with their commercial network and social elites, whereas they are relatively rare in the figurative art of Palaeolithic and Neolithic.

Why is it so? “The Origins of Monsters” advances an interesting hypothesis: composites, Wengrow writes, “imply within their own structures certain principles of integration that were weakly developed in prehistoric societies, becoming prominent only with the emergence of urban life (p. 59)”. It is only in the first cities that the physical and social world became divided “into standard and interchangeable subunits” (p. 7) and the success of composite images, themselves representing beings built with “interchangeable subunits”, is interpreted as a reflection of these new circumstances.

While surely fascinating, how convincing is this hypothesis? Obviously, its plausibility chiefly depends on the main assumption of the relative absence of images of composites in prehistory, and of their later success. I am far (very far) from being an expert, but I would have liked to see a more systematic – quantitative - analysis of the empirical support. Wengrow dismisses well-known prehistoric “monsters” such as the Löwenmensch (lion-man) figurine or the Breuil’s “sorcerer” as isolated and rare exceptions, and takes later examples of composites (say the Mesopotamian lion-faced Humbaba) as representative for the period. I would be curious to know what art experts and historians have to say about that. A different line of reasoning would involve considering contemporary hunter-gatherer cultures. If the “interchangeable subunits” hypothesis is true, composites should not be particularly successful there, as individuals in these cultures do not experience the social and physical subdivision typical of urban societies. Wengrow quickly mentions that, in fact, composites are present in hunter-gatherers performances, but less in their plastic and visual art, substantiating this statement with a couple of references to Ingold and Descola (p. 30). It seems that there is here ample space for additional ethnographic and comparative studies here.

In addition, differently from the MCI explanation, it is difficult to understand exactly what kind of cognitive mechanisms would enhance the salience of representations of composites, just because “interchangeable subunits” become more prominent in the social environment. The MCI explanation is supported by psychological results: what about the “interchangeable subunits” hypothesis? One could imagine to assess it by testing how appealing images of “monsters” are for children, and the prediction should be that they would become appealing only when children are able to appreciate the modular nature of their social environment. I am unaware of studies of this kind, and nothing similar is discussed in the book.

In sum, as a minimum the “interchangeable subunits” hypothesis cries for support from ethnography, as well as comparative and developmental psychology. That is why Wengrow lost me in his conclusion, claiming the superiority of its “archaeological – rather than laboratory-based or ethnographic – approach” (p. 112). I really would like to see in our field more ideas like the ones presented in The Origins of Monsters, but the book left me with the feeling that the “hard part” is yet to be done.

David Wengrow 17 January 2016 (12:51)

Alberto Acerbi asks what art experts and ancient historians make of my overall characterisation of the visual record. Over the past five years or so I have presented it to many audiences of this kind, as well as to archaeologists and anthropologists. Of course I can’t summarise the many reactions, but so far none of them obliged me to rethink the general patterns of distribution for composite figures, as presented in the book. Whether these patterns can be generalised to regions and periods not treated there (such as the prehistoric Balkans or modern-day Amazonia) is another matter. Mine is a middle-range study of cultural transmission, dealing with significant chunks of time and space. It does not assume or require a universal model and if other, significantly different trajectories of image making exist it would be fascinating to compare them, and try to account for the differences. For published views by art historians and archaeologists, I direct Alberto (and others) to Jeremy Tanner’s comments in this forum, and also to a review of the book in Times Literary Supplement (September 12th, 2014) by Christina Riggs.

Responding to the rest of Alberto’s response is difficult because he distils my argument down to such a simplistic formulation that I can barely recognise it, let alone try to defend it on those terms. He is right of course that my argument stresses the relative infrequency of imaginary composites in Old World prehistoric art, as against their relative popularity in early urban and literate societies of Eurasia and North Africa, and then it tries to explain this phenomenon. But nowhere do I propose a single prime mover, let alone an “inter-changeable subunits hypothesis” of the sort that could be tested under laboratory conditions.

My conclusion, which Alberto does not like (but seems also to misread), emphasises how formative elements of human cognition – using Tomasello’s terms – may result from ‘complex conjuctures of social, technological, and moral processes’, which the book seeks to unravel. No mono-causal hypothesis here. Nor do I assert that archaeology is a superior method of reconstruction – only that it is a necessary supplement to laboratory-based and ethnographic work if we are to avoid false assumptions and blind alleys in the study of human cognition.

Early on in the book (p.4) I give an example of what, in my opinion, is one such blind alley. There I discuss experimental work done in the 1990s by cognitive psychologists. They were trying to establish if spontaneously representing fantastical beings (of the kind that exist only in the mind) might itself involve a distinct neuro-cognitive mechanism. Children on the autistic spectrum formed part of the scientific control group, on the assumption that they find ‘spontaneous and fantastical acts of imagination’ challenging to a greater degree than neuro-typical children (and see, more recently, Low et al. 2009. ‘Generativity and imagination in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from individual differences in children’s impossible entity drawings’, in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology 27: 425-44).

The experiment used a standard protocol for drawing “impossible” beings, designed by Annette Karmiloff-Smith (1990. ‘Constraints on representational change: Evidence from children’s drawings’. Cognition, 34, 57–83). I find the line of questioning here fascinating. But as with so much experimental work of this kind, it appears to be largely assumed that physical images offer faithful reflections of evolved mental representations, projected mirror-like onto the material world. Sensory-motor skills, developed in relation to particular tools and materials, were little considered; nor were socially learned and historically patterned expectations about what can and cannot be seen in the world.

My own, very different kind of study draws attention to the centrality of such environmental and historical factors in shaping what we might otherwise (and wrongly, in my view) consider to be purely free and spontaneous acts of human perception and imagination. As Jack Goody frequently pointed out the visual and tactile environments we inhabit - and which frame our experience of social learning - are to a significant degree a product of the Bronze Age. We use writing to communicate, we live and work in brick-built cities, we sit on chairs and sleep on beds, eat our food with metal cutlery, teach our children abstract rules of mathematics, give them Lego to play with, and fill their heads with mechanically (or now digitally) reproduced images of all kinds of fantastic beings. I don’t think all this enculturation could possibly be unworked through some magic of the laboratory.

If work by archaeologists, anthropologists, and other culture historians prompts experimental psychologists to pay more attention to such factors, then it is surely doing them a service. Incidentally I don’t feel it’s necessary, in such cases, to ask whether one method of approaching human cognition is superior to another; but simply to acknowledge that archaeological, ethnographic, and laboratory based approaches offer different and complementary paths of access to any given cultural phenomenon. None of these fields, in my opinion, can validate the others to a greater or lesser degree. They are distinct and mutually informative ways of making valid inferences about human cognition; and they should be given roughly equal weighting.

Why, as Alberto seems to imply, must the path of inference always lead from the laboratory to the cultural-historical record? Surely it can just as well go the other way too? I think this would also be my response to Martin Fortier’s earlier comments on developing an epidemiology of material representations. My thanks both to Alberto and Martin for their stimulating thoughts on the book. Perhaps we somehow need to try and link together the various threads of the discussion so far?

Alberto Acerbi 18 January 2016 (11:57)

First of all, I want to thank David Wengrow for his swift and thorough response to my comment. Overall, I think that, despite some differences in tone, we agree on the main point. Nowhere, in my comment, I wrote or implied that “inference always lead from the laboratory to the cultural-historical record” (incidentally, this would be against my own research!), but that it is an excellent opportunity, when an hypothesis developed to fit archeological data can be tested in the lab, or in ethnographic contest, to do it. Just to be sure: I would say exactly the same if the hypothesis would have been formulated starting from psychological experiments, or ethnographic/comparative analysis. David agrees - I subscribe word-by-word the penultimate paragraph of his answer - so there is not much to say here, but I still wonder whether this message transpires as clearly in The Origins of Monsters.

Finally I would like to spend again some words on my interpretation of David’s hypothesis. I wrote in my comment that it can be described as an explanation of the success of “very specific cultural items” (images of composites in early urban societies) due to the combination of universal cognitive factors (the success of minimally counterintuitive representations) and local, socio-economical ones (which I called, probably clumsy, the “interchangeable subunits” hypothesis). David thinks that this interpretation is “simplistic” and, of course, if he thinks so, this is it. To me, however, this hypothesis, exactly because in this form, is very interesting, clear, and can be quite straightforwardly used to generate several testable predictions. It is exceedingly rare to find hypothesis of this kind in social sciences, and especially in anthropology: in fact, as I wrote in my comment (“I really would like to see in our field more ideas like the ones presented in The Origins of Monsters…”), the main strength of David’s excellent book - from my very personal point of view, of course - lays mainly here.

James Waddington 18 January 2016 (14:10)

This is a really interersting and productive conversation. The investigation of monsters, reticulated clades, is one of the few areas of present cultural evolution analysis which seems to me to deal in units, lions' heads, dragons' claws, well defined enough and discrete enough to be examinable in terms of variation, transposition, selection and transmission. Clearly it would be presumptuous to comment further without reading the book, which I now hope to do.