- 'The Origins of Monsters' Book Club

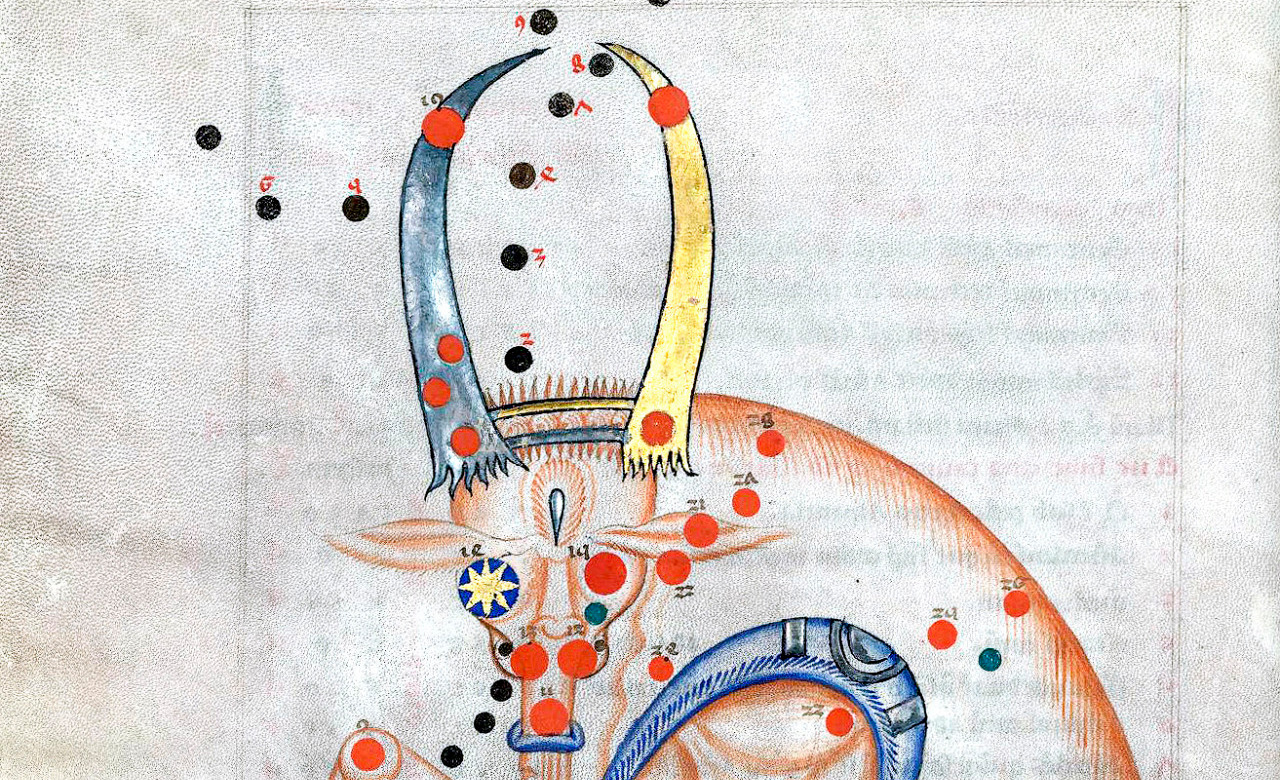

Chimaeras as attractors: Epidemiology and cultural variation

David Wengrow’s brilliant Origins of Monsters is a rare example of an archaeological study that addresses an important "middle-level" causal question (in this case, Why the proliferation of chimerical images in the Bronze Age?) from the standpoint of a scientifically sophisticated model of cultural evolution. The transmission of a specific iconography is of course a locus classicus in both history of art and archaeology, but it has been generally addressed in purely formal terms, without much consideration of the cognitive processes required to process and recreate visual information, with brilliant exceptions. So Wengrow takes over where distinguished predecessors like Aby Warburg left off, with of course the benefit of a much more precise psychology.

Before discussing Wengrow’s rich material and fascinating discussion, it may be of help to do some conceptual cleaningup. In particular, some confusion about the underlying assumptions of evolutionary models, and specifically of an epidemiological framework, may result either from Wengrow’s own formulations, or more likely from the way we discuss his hypotheses in the course of these exchanges.

For example, Wengrow at various places mentions the “limits” of epidemiological approaches. He also suggests that change or variation are not expected in such models. But it would be a misunderstanding to consider that evolutionary psychology can only explain cultural universals. This fits with a common understanding of ‘genes’ providing immutable features of organisms and ‘environments’ their variation. But that is of course misleading (Sperber, 2005). Indeed, some of the best examples of evolutionary models explain how evolved systems are designed to modulate responses as a function of external information. For instance, some young women mature and reproduce early, in their teens, while others delay reproduction. One of the main factors involved is the presence of fathers in their households during early childhood, which triggers an unconscious estimate of the extent of paternal investment in their social environment (Ellis et al., 2003; Ellis, Figueredo, Brumbach, & Schlomer, 2009). In other words, the evolved reproductive system is designed to motivate different behaviors, contingent on specific environmental cues. Or, people in the same town adjust their level of cooperation and trustworthiness, depending on a largely unconscious perception of uncertainty in their environment (Nettle, 2010; Nettle, Colléony, & Cockerill, 2011). So a single life-history strategy process, as a result of natural selection, results in either a ‘fast and furious’ or a prudent and moderate approach to life’s choices (Sheskin, Chevallier, Lambert, & Baumard, 2014). There are many more examples. In fact, a central lesson of evolutionary biology is that most instincts are conditional, not of the “do x if y” form, but rather “do x if y, given conditions c1, c2, ... cn”.

Related to this is the fact that neither an epidemiology of culture, nor the broader evolutionary psychology framework it is a part of, can make use of such a vacuous distinction as ‘nature’ vs. ‘nurture’. (Wengrow’s use of these terms, page 82, is the only blemish on a magnificent book). The terms are simply meaningless. If young girls in a poor social class react to their jailed father’s absence with earlier menarche and earlier interest in sex, is this ‘nature’ or ‘nurture’? The terms have no place in a causal explanation of human behavior.

Enough jeremiads and quibbles. The central question of the book, and the hypotheses presented by Wengrow, are of much greater interest.

So, why this proliferation of composites? As Wengrow points out, the question is more complex than this terse verbal formulation may suggest. The first specific question is, Why this (roughly accurate) cultural transmission of visual representations constructed on the same principle, of combining parts of distinct animals in a single body? This Wengrow addresses in terms of intuitive biology, of the expectations we spontaneously develop as regards invariances in living species. Because of the intuitive connection between species identification and apparent Bauplan, composites constitute a salient violation of our domain-specific expectations for animals, which makes them more attention-grabbing than standard representations.

Wengrow’s explanation shows how a cognitive evolutionary framework, not only answers old questions (e.g., Why combine parts of several animals?), but also highlights features that in other frameworks, as in the classical study of iconography, are not explained because they are simply not considered. In this case, why do people use accurate representations of each body part that is used in a chimaera? Also, why are these fantastical creations ‘anatomically correct’? That is, when adding fins to a lion’s body, why do the creators of chimeras place them in the ‘right’ place on the back? In the standard description of chimeras as fantastical, we could predict imaginary body parts as well as real ones, and inappropriate positioning of real ones. The odder, the better. By contrast, the cognitive interpretation suggests that the effect of incongruous, counter-intuitive chimeric combinations is stronger if all parts can be quickly identified and associated with their species of origin, as Wengrow points out.

This, by the way, is an example of what epidemiologists would call a cultural attractor, a combination of representations whose probability of occurrence at a generation g increases if either that particular combination, or other specific ones, are frequent at g-1 (Claidière, Scott-Phillips, & Sperber, 2014; Sperber & Hirschfeld, 2004). To simplify, the implicit notion that the lion’s fin must be in the middle of its back, would be reinforced by ‘incorrect’ exemplars that place it on the lion’s paws. This kind of hypothesis can be tested, either by studying the actual occurrences, if one is lucky enough to have such a corpus, or by experimenting with cultural transmission in the lab.

David Wengrow also addresses the question, Why this proliferation of composites there and then rather than before or elsewhere? but tells us, rather depressingly, that cultural epidemiology has “no way of explaining why these images become stable and widespread only with the onset of urban life and state formation” (page 88). I found the statement baffling, as the various hypotheses Wengrow puts forward in the following pages strike me as perfectly fine epidemiological conjectures. (Unless of course one assumes that epidemiology and more generally evolutionary psychology are only about cultural universals... but see above).

So, for instance, Wengrow points out that there may be a causal connection in the coincidence between the appearance of composites and the spread of mechanical reproduction (page 82). If I follow his reasoning, the link may be that the onset of urban life and the development of intensive trade between distinct polities resulted in cosmopolitan exoticizing, so to speak, of which Wengrow describes three distinct modes, transformative (exotic goods upset traditional conventions), integrative (different conventions are blended in an international style) and protective (imagery is construed as a barrier to foreign conventions), respectively (pp. 91ff).

My main request to David Wengrow would be to clarify the differences between these modes, to speculate on what specific psychological motivations and processes underpin each of them, and explain to what extent they are mutually exclusive. This is important, as these distinctions about models of transmission constitute the rudiments of a genuinely epidemiological model of this extraordinary cultural development. Obviously, the constraints of taphonomy mean that specific answers are bound to remain speculative. However, such speculation, if made psychologically precise, could be supported or challenged by relevant evidence from other cultural trends or from laboratory experiments. For instance, under what conditions would a ‘protective’ mode, where imagery is used as a threat against foreign ways and people, favor the creation of fantastic composites rather than simply terrifying images?

It is of course unfair to ask an author to provide a second book that would answer all the questions raised by the one being discussed. But that is what happens when you engage in great scholarship. Anthropologists and other scientists should be grateful to Wengrow for such a precious contribution to the epidemiology of culture.

Bibliography

Claidière, N., Scott-Phillips, T. C., & Sperber, D. (2014). How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 369(1642). doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0368

Ellis, B. J., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., Pettit, G. S., & Woodward, L. (2003). Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual activity and teenage pregnancy? Child Development, 74(3), 801–821.

Ellis, B. J., Figueredo, A. J., Brumbach, B. H., & Schlomer, G. L. (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk: The impact of harsh versus unpredictable environments on the evolution and development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20(2), 204–268. doi: 10.1007/s12110-009-9063-7

Nettle, D. (2010). Dying young and living fast: Variation in life history across English neighborhoods. Behavioral Ecology, 21(2), 387–395.

Nettle, D., Colléony, A., & Cockerill, M. (2011). Variation in cooperative behaviour within a single city. PLoS One, 6(10).

Sheskin, M., Chevallier, C., Lambert, S., & Baumard, N. (2014). Life-history theory explains childhood moral development. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(12), 613–615. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.08.004

Sperber, D. (2005). Modularity and relevance: How can a massively modular mind be flexible and context-sensitive? In S. L. Peter Carruthers (Ed.), The Innate Mind: Structure and Content.

Sperber, D., & Hirschfeld, L. A. (2004). The cognitive foundations of cultural stability and diversity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(1), 40–46.

Olivier Morin 19 January 2016 (08:25)

This is a comment not just on Pascal’s post, but on two other participations to the book club, one by Carmen Granito & Thom Scott-Phillips, and one by Karolina Prochownik (both to be published later this month). All three, as I read them, make more or less the same point: Wengrow is wrong to think that his work underscores the limits of cultural epidemiology; it is in fact a fine addition to it. The things that drive cultural change (aka the factors of attraction) can be local, contingent, and dependent on political contingencies—we never denied it.

That’s always a good point to make, but here’s what I worry about. Studying cultural diffusion, and studying it in a way that is highly sensitive to local social and political contexts, is something archaeologists have been doing for a long time now. They should all be decorated for their contribution to cultural epidemiology, but… well, I fear they won’t feel as honoured as we’d like them to be. More likely to say, “Thank you for the medal, very grateful”—and never wear the trinket again. The real question (that David Wengrow might be too polite to ask) is: What does cultural epidemiology contribute to this kind of research, that other approaches don’t?

Local factors will always be best studied by local specialists; what cultural epidemiologists bring that others don’t is a set of hypotheses very general in scope, inspired by findings from psychology, including various brands of developmental and evolutionary psychology. These hypotheses are universalist in the important sense that they claim to describe biological and cognitive mechanisms that are at work in the vast majority of humans. As Pascal notes, this does not, of course, commit us to the view that people behave the same everywhere: identical mechanisms can produce variable outcomes in different contexts; but such reasoning is still beyond the pale in many anthropological discussions where claims of universal validity are regarded with suspicion, to put it mildly.

General psychological hypotheses, not social or political particulars, are our bread and butter. Wengrow and his colleagues are absolutely right to regard such hypotheses as the key contribution of our aproach, and quite entitled to fault cultural epidemiology if they fail.

As I understand it, the hypothesis that Wengrow starts his book with (but ends up questioning the relevance of) is that images of composite animals are “MCI” and are more readily invented and diffused than other animal representations (all else being equal and barring local perturbations), by virtue of a very general proclivity of the human mind that makes us favour all things MCI. If this is indeed what epidemiologists should predict (would you agree, Pascal?), and if Wengrow is right that images of composite animals hardly ever emerge without a variety of factors that includes an organised state, the mechanised reproduction of images, and extensive trade networks, then the hypothesis is indeed in trouble, and so is cultural epidemiology’s original and specific contribution to this particular problem.

David Wengrow 19 January 2016 (18:27)

An objection I faced when initially presenting this research – mainly to archaeologists, ancient historians, and art historians – concerned the images themselves, and their status in relation to human cognition. It was suggested on more than one occasion that images ‘combining parts of distinct animals in a single body’, as Pascal Boyer puts it in his response, might not really be ‘minimally counter-intuitive’ at all, at least not in the sense intended by Boyer. It is gratifying now to have it “from the horse’s mouth” that we are indeed talking about roughly the same thing.

It is true that Pascal has not written specifically on images. But, rather than be put off by such objections, I tried instead to adapt the principle of minimal counter-intuitiveness to the domain of visual cognition, as supported by psychological data. Now a second objection has been raised by Martin Fortier and others, in earlier posts: the experimental work on animal recognition, on which I rely for my hypothesis, does not relate specifically to the cognition of images. Surely, they ask, I cannot be simply assuming that principles governing innate biological classification (as discussed by Scott Atran for instance) are the same as those governing the perception and transmission of images? The experimental work on images, they suggest, has not yet been done.

But I would argue this is not in fact so. In one case (Davidoff/Roberson [2002] ‘Development of animal recognition’, in Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 81) subjects were presented with pictures of animals, or bits of animals – not real ones. And in the other (New/Cosmides/Tooby [2007] ‘Category-specific attention for animals reflects ancestral priorities, not expertise’. PNAS 104) the stimuli used were ‘colour photographs of natural complex scenes’; again, not actually living animals.

Of course you wouldn’t know this from the titles and empirical claims of these articles, and that is exactly what I mean about the problem of ‘genre-blindness’ (or ‘culture-blindness’) in at least some experimental psychology. Perhaps it makes no difference whether the animals are depicted or real, but whatever the case these particular experiments are in fact more securely tied to the perceptual world of human-made images than to the perceptual world of living kinds.

The same is true of some other quite recent experimental work on the role of contours and edge alignments in animal detection. With its theoretical roots in the Gestalt psychology of Kurt Koffka, research of this kind now uses software like the Berkeley Segmentation Dataset, rather than hand drawings or mechanically reproduced images on cards, as was once the case. BSD carves up images into meaningful regions and groupings – a wonderful way of generating animal forms on a digital screen for experimental subjects to look at, but very far from placing them in a moving landscape full of living, breathing, snorting, howling wildlife (see for instance Edler/Velisavljević [2009] ‘Cue dynamics underlying rapid detection of animals in natural scenes’. Journal of Vision 9; and Martin/Fowlkes/Malik [2004] ‘Learning to detect natural image boundaries using local brightness, colour and texture cues’. IEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 26].

All this experimental work, in my view, constitutes an unheralded contribution to the study of images, and I feel comfortable using it as such.

Like Maurice Bloch, Pascal asks for clarification on my three modes of image transfer: ‘transformative’, ‘integrative’, ‘protective’, for which he provides an elegant summary. I’ve tried to clarify this in my reply to Maurice, but will go a bit further, because Boyer asks whether I can specify the different psychological underpinnings of the various modes. I suspect what he has in mind here is something like Harvey Whitehouse’s distinction between ‘doctrinal’ and ‘imagistic’ modes of religious experience, which activate different parts of the human memory system (semantic versus episodic). Could my distinctions have a similarly clear neurological basis?

The short I answer I think is ‘no’. They are not to be taken the same way as Whitehouse’s ‘modes’, and I am beginning to regret using the term ‘mode’ at all, because I can see how it might give a slightly false impression. In the book I quite deliberately kept the boundaries between the three modes fuzzy and stress how they may shade into one another, or indeed be aspects of the same historical process (as discussed for ‘protective’ and ‘transformative’ modes in my reply to Jeremy Tanner).

My ‘modes’ frame contexts of transmission at the scale of institutional change (e.g. processes of state formation, colonial encounters), rather than the scale of individual psychology. They do not meet the epidemiological requirement that macro-level distributions of cultural facts are to be explained in terms of micro-level cognitive processes. But they were never intended to fulfil this function. The micro-level comes in elsewhere: in the cognitive and perceptual machinery that – under certain identifiable conditions – makes composite figures into hyper-effective vehicles of cultural transmission and political transformation.

Olivier Morin, Martin Fortier, and Alberto Acerbi have since raised other questions, specific and general, that I have yet to answer satisfactorily. What about ethnographic cases of hunter-gatherers and other non-state societies possessing a rich and stable imagery of composites? How exactly and how far does my study engage with the epidemiological agenda? Do I come as an archaeologist (shovel in hand) to bury or to praise it? Neither, in fact – but this post is probably already overlong, so I will end here for the moment, and offer my very sincere thanks to Pascal Boyer for his close engagement with and critical appreciation of the book.

Hugo Mercier 23 January 2016 (18:07)

Apologies for being slightly out of place, since I want to address Olivier's comment in a way that doesn't particulalry relate to the rest of the book club (which is fantastic btw, thank you all!).

Olivier, you say that "if Wengrow is right that images of composite animals hardly ever emerge without a variety of factors that includes an organised state, the mechanised reproduction of images, and extensive trade networks," then not only is the hypothesis "that images of composite animals are “MCI” and are more readily invented and diffused than other animal representations (all else being equal and barring local perturbations), by virtue of a very general proclivity of the human mind that makes us favour all things MCI" false (trivially), but also "cultural epidemiology’s original and specific contribution to this particular problem."

Having just reread your book, I think I see where you're coming from, but I still think this is too categorical. Why couldn't cultural epidemiology make an original contribution by helping explain some features of the phenomenon in question rather than the whole thing? In the case at hand, it might help explain why the images that spread thanks to the factors highlighted by Wengrow take the form they take. Similarly, you see your work on writing as part of an epidemiological approach (right?), even though writing requires criteria similar to Wengrow's to emerge. In your terms, the factors that motivate the production of some representations would be chiefly determined by local social factors, but attraction would still play a role.

Olivier Morin 23 January 2016 (18:07)

Thanks for the clarification Hugo.

One of my answers applies only to this case: I don’t think the view that monsters are MCI is true at all. I explain why in my post next week… stay tuned!

More generally, this debate might be, in part, a matter of epistemological tastes. Some people like their theories to have many degrees of freedom: to explain a wide variety of phenomena with a model of many variables, each of which might be overridden by the others. Such a multi-causal approach is clearly the one favoured by David Wengrow. These models are excellent from a descriptive point of view, but their predictive power is quite low. A model with many parameters (of undefined weight) can accommodate a wide range of results. It does not say anything false, but it doesn’t take many risks.

Others, of a more reductionist bent perhaps, like models that give them a proportionate bang for their buck, so to speak: a good causal hypothesis makes surprising predictions, it has informative value in addition to its descriptive value. My tastes carry me towards this second option. The risk of over-fitting (or retro-fitting), i.e., of helping oneself to ad hoc variables to accommodate any and all exceptions, is just too great. So I would make a plea to keep epidemiological hypotheses as simple as possible (though not more). The risk of embracing multi-causal models where fundamental psychological mechanisms are often (or always) overwhelmed by local and contingent factor, is quite simple. The psychological hypothesis ends up not doing any explanatory work. This, I suspect, is what ends up happening to MCI theory in David Wengrow’s model (and I am not immune from the danger myself).

Incidentally, this difference of taste between people who prefer descriptive models (at the risk of over-fitting) and those who prefer informative models (at the risk of reductionism) might unlock some misunderstandings between David Wengrow and some of the debaters here. David Wengrow claims that monsters should be fostered by the mechanical reproduction of images—except when they aren’t, as in China. Monsters should thrive in big, centralised states—except when they don’t, as in Iron Age Greece. Composite monsters should be appealing—except that in most of human history, they weren’t. Alberto, or Mathieu (like me) see this flexibility as a problem, or at least as a sign that the model is incomplete, while David Wengrow presents it as a strength. Is he wrong? I don't kow. I can understand why, when one values accuracy, descriptive sophistication, and erudition, above other things (as archæologists do and perhaps should), one can prefer such models to simplified and risky ones. Perhaps we simply need to acknowledge a conflict of scientific tastes here.

Olivier Morin 23 January 2016 (18:45)

by the way... "re-reading my book"? Surely you have better to do ;o)

Hugo Mercier 24 January 2016 (08:09)

Thank you for your reply Olivier. I see your point and will be looking forward to reading your post!