- Technical Flexibility and Rigidity Webinar (private)

Week 14 – Relevance-based emulation as a tool for knowledge transmission and technical innovation

This early draft was authored by György Gergely and Ildikó Király.

In light of recent theories, human cultural transmission fundamentally relies on the specialized cognitive adaptation of an imitative action-copying mechanism that accounts for the faithful reproduction and transmission of shared cultural action skills (Tennie, Call & Tomasello, 2009; Legare, Wen, Herrmann & Whitehouse, 2015; Tomasello, 1999).

These assumptions converge in their emphasis on attributing a central role to humans’ specialized cognitive adaptations for conservative action-copying and behavior imitation to account for the faithful transmission and maintenance of a culturally shared repertoire of action forms in human social groups across the generations. At the same time these theories also tend to recognize and acknowledge on empirical grounds that a certain amount of variability and flexibility appears to be present in the cultural reproduction of action forms (Legare & Nielsen, 2015). Yet, they tend to diagnose and restrict its presence and differential degree to particular domains of different kinds of cultural action forms, primarily distinguishing between goal-directed transitive action skills that serve instrumental technological functions versus intransitive non-instrumental actions like ritual gestures (or concatenated series of goal-demoted and repetitive stereotypic action sequences that are characteristic of jointly and publicly performed traditional social practices which appear to serve social rather than instrumental functions, see Legare & Nielsen, 2020). They also present a variety of different accounts to identify (and explain) what input conditions and action domains do selectively induce more flexibility in emulative reproduction and tolerate the generation of more variability and production of action variants versus what factors are likely to trigger the mechanisms of exact behavior copying and require only the production of conservative and precise imitative action replications reducing thereby the generation of variability in the reproduced action forms (Legare, 2019; Legare & Nielsen, 2015; Tennie & van Schaik, 2020).

These accounts often attempt to motivate and explain the differential distributions of induced rigidity versus flexibility of reproduction in the different kinds of cultural action domains by proposing alternative functions that these transmission processes may serve. For example, they point out that some flexibility may be adaptive in the domain of reproducing transitive action skills that serve instrumental functions since variability in the reproduced forms can support the emergence of innovation of more adaptive functional variants (Clegg & Legare, 2016). An alternative type of explanation points at the consequences that the differential amount of transparent constraints associated with the various type of cultural action domains may represent: identifying causal or teleological opacity of actions (like in the case of intransitive goal-demoted ritual actions or repetitive series of traditionally stereotyped intransitive action sequences that serve no transparent instrumental goals) as a causal factor that may induce conservative and exact behavior copying in order to inhibit the generation of variability of reproduced forms as these would endanger successful reproduction, recognition, and maintenance of the opaque cultural action forms (Kapitány & Nielsen, 2019). In contrast, some argue that since transitive skills whose instrumental function and causally constrained sub-goal-final-goal serial structure are both transparent to the learner, such transparency may induce more flexibility and variation in reproducing the observed action components because the transparent causal structure and goal function of the novel cultural skill can provide constraints and guidance to foster the creation of innovative variants among the reproduced action forms (Legare & Nielsen, 2015).

We need to add here that this dichotomy largely overlooks the important fact that the repertoire of cultural actions that the social learner needs to acquire also presents numerous cases of transitive actions serving instrumental functions which nevertheless frequently contain causally opaque component actions of sub-goals. Equally importantly, such instrumental actions often serve additional social functions such as culturally constituted action manners that are not transparent, and are more costly to perform in efficiency terms (a simple example is that eating with hands is possible in lot of circumstances, however, cultural practices introduce the use of different utensils, like special knives, or chopsticks, the specific functional, causal properties of which are not always transparent for the first sight). The above approaches still seem to hypothesize that perceived opacity induces high-fidelity action copying whether opacity occurs in ritual actions with non-instrumental functions or as part of transitive actions that primarily serve instrumental functions.

We believe that this hypothesis is fundamentally mistaken, observing novel cultural actions – even if they contain causally opaque components - do not induce the production of conservative motor replicas without variation and there is no specialized evolved motor behavior copying mechanism selected to serve cultural action replication. We support the argument that emulative variation may be an important source of the emergence of changes of cultural forms that can lead to the enrichment of the cultural action repertoire transmitted. Variability of reproduced action forms allows for and can support the emergence of inventions, as generating more variability in reproduced action forms can create more adaptive or differently adaptive action variants (also leading to their consequent stabilization in the cultural repertoire). Therefore, variability of reproduction is a major source of the ratchet effect in cultural transmission leading to the cumulative nature of human culture that characterise its transformations through cycles of intergenerational transmission.

We shall argue and demonstrate that the dedicated social learning mechanisms selected for acquiring and culturally transmitting the repertoire of culturally shared action skills demonstrated by social agents belonging to one’s social and cultural community is emulation driven by demonstrations of novel intentional actions that are socially observed in one’s cultural environment.

The phenomenon of context-sensitive selective imitation of causally opaque instrumental actions

Below we shall present new empirical evidence to test and refute the widely held assumption that the causal opacity of a novel cultural action is a sufficient input condition to activate human cultural learners’ evolved imitative behavior-copying mechanism. This predicts that when an infant observes a social agent perform an unusual, sub-efficient and therefore causally opaque goal-directed action, the infant will learn the novel action by automatically producing a faithful imitative behavioral replica of the demonstrated act. In contrast, we shall argue and provide evidence to show that the opacity of a novel action does not induce faithful behavior-copying in the observational learner that would lead to the reproduction of motor replicas of the acquired opaque action. Furthermore, we shall show that demonstrations of causally opaque cultural actions do not inhibit emulative flexibility and variability, but rather it can induce the production of alternative action variants by the learner who attempts to reproduce the relevant novel action demonstrated.

We propose that the central assumption that opacity of novel actions induce faithful behavior copying and inhibit the production of variability of action alternatives is fundamentally mistaken both when applied to the domain of non-instrumental ritual actions serving social functions or to the domain of transitive actions associated with instrumental functions. However, our studies below will be restricted to test this assumption only in the domain of transitive instrumental actions where the presence and function of causally opaque action components in cultural forms of instrumental actions has been less often recognized and received less attention in theories of cultural transmission. The empirical investigation of opacity and variability of transmitted action forms is outside the scope of the present paper and will need to be addressed separately by future research.

The illusion of imitation

We shall test these hypotheses using new versions of the ’head-touch paradigm’ originally designed to investigate imitative re-enactment of novel causally opaque actions by infants. This paradigm was initially used by Gergely Bekkering and Király (2002) to demonstrate that imitation is a selective, inferential, and context-sensitive learning mechanism.

In their study infants watched an adult sitting in front of a table with a touch-sensitive lamp on it. The experimenter first placed her hands on the table next to each side of the lamp. Then she performed an unusual action to illuminate the lamp by bending over it to press it with her forehead (‘hands free’ condition). A separate group of infants was tested in an alternative condition where the model first pretended to be freezing telling the infant that she was cold, then proceeded to put a blanket around her shoulders that she was holding with both hands ‘hands occupied’ condition). Then she demonstrated the same unusual head-action as was presented in the ‘hands free’ condition: She illuminated the lamp by bending over it and pressing it with her forehead. In the test phase the infants were given the touch lamp and were encouraged to play with it themselves. In the ‘hands free’ condition most of them (69%) used their head to illuminate the lamp (cf. Meltzoff, 1985). However, in the ‘hands occupied’ condition, only a small proportion of infants (21%) performed the head action to light the lamp; the majority of them just used the more efficient (but undemonstrated) method of pressing the box with their hands.

This pattern of selective imitation of the same head-touch action indicated that infants were sensitive to the differential context in which the model presented the unusual head-action. In the ‘hands free’ condition the model’s sub-efficient and unusual head-touch action must have appeared causally opaque given that her hands resting on the table were free and she could have used them to press the lamp (a more efficient and familiar action alternative). Nevertheless, she opted not to use her free hands, but instead she demonstrated to the infants the causally opaque (sub-efficient and more costly) head-touch means action to achieve the goal of lighting up the lamp. In contrast, in the ‘hands occupied’ condition, where the model’s hands were not free to use (being occupied with holding the blanket), the demonstrated head-action was justified as being the causally most efficient alternative means action available for the model given the constraints of the situational context.

This pattern of data has been interpreted as evidence that children apply the rationality principle in the process of social learning: they take into account the efficiency of observed actions to achieve a specific goal or outcome within a context when deciding whether to reenact a specific behavior or not. Nonetheless, when children selectively imitated the causally opaque head-touch action in the ‘hands free’ condition, they appeared to imitate the modeled action This finding seems to provide support for the assumption that causal opacity of an observed action induces high-fidelity behavior-copying in the cultural learner. The results also seem to be in line with the proposal that faithful copying of novel instrumental actions may be the result of a copy-when-uncertain strategy in social learning (Rendell et al.2011; Toelch et al. 2014). In this view, children choose between different strategies, they imitate with high fidelity behavior what is causally opaque to them, while they apply alternative goal-directed approaches flexibly (and so they can innovate) when learning behavior that has a transparent physical causal mechanism (Legare et al. 2015; Legare & Nielsen 2015). Indeed, high-fidelity imitation, as a strategy may be so useful for learning novel, but opaque behaviors that its benefits can outweigh potential efficiency costs (McGuigan et al. 2007). The question is how exactly children benefit from form-copying in case of transitive actions?

First, the problem emerges: in what way children learn through copying? If the rule is to copy what is opaque (see Tennie, 2009), then how children arrive to understand which action is instrumental by nature and which is conventional? Furthermore, if they learn an action by copying how then they find ways to introduce modifications to it?

Indeed, it is claimed that the switch between copying and alternative re-enactment strategies is driven by interpreting an action as being conventional or instrumental (Clegg & Legare 2016, Herrmann et al. 2013). If thus copying is a result of interpreting the observed behavior immediately as conventional just because it being opaque, the possible constraint arises that they interpret it by default differently, and also store it separately from behaviors they do not copy.

This suggestion however is problematic in light of the fact that then no solution for distinguishing conventional manners from complex instrumental variants (probably opaque for the first sight) remains. Consequently, there is a hiatus in the explanation on how the strategy of copying could contribute to the deepening of instrumental knowledge.

In brief, the above approaches claim that different forms of social learning are induced by different demonstration contexts, and thus suggest that learning a new behavior that was presented as being opaque would bring about high-fidelity copying; in contrast, a new behavior being transparent or justified in a situation would induce variability in re-enactment.

As such, the concern is open: facing an opaque transient action, do children interpret it as conventional or not? If the suggestion is that what they find opaque they read it as conventional, and learn through imitation, they probably keep it separately from behaviors that are learned through emulation.

Nonetheless, in order to become advantageous, copying should offer solutions for solving similar problems in the future. Yet it is unclear, how the strategy of copying could promote generalization across contexts. An alternative approach is that there is no different strategy beyond learning conventional and instrumental actions. Rather, the same learning strategy is applied for both opaque and transparent observed actions, yet in the case of opaque behaviors, more elements are included in reenactment from those parts that are highlighted as being related to the overall goal. Let us investigate what strategies infants pursue when they turn to follow more closely the modeled behavior and the relevant context within which it is presented. We propose, that the guidance of ostensive communication, experience with alternative variants and repetition should be the route through which instrumental actions are separated from conventional ones.

Is there form-copying?

In order to investigate closer the mechanism beyond selective reenactment of observed behaviors, we analyzed further the performance of children in follow-up studies with the head touch paradigm.

With the aim of investigating the underlying mechanism behind imitative learning, Király and colleagues (2013) ran follow-up studies with the head touch paradigm. They found that 14-month-olds reenacted the novel arbitrary means action, the head touch, only following a communicative demonstration of the hands free condition, and not in an incidental observation context. The authors proposed that the selective reenactment of behavior observed in the communicative context, specifically the imitation of the novel arbitrary means in the hands free context, reflects that young children are prepared to learn novel actions the function of which is not apparent at first glance. In the absence of the possibility to exploit their individual learning strategies, they rely on the communicative signals of experienced others. Infants’ interpret the action demonstrations as communicative manifestations of novel, yet culturally relevant means actions to be acquired. Because of the communicative signals that accompany the action demonstration, infants construe the action manifestation as a communicative action rather than as a purely instrumental action (Csibra & Gergely, 2011; Gergely & Jacob, 2012). They interpret the situation as a teaching context where the demonstrated action and the communicative context together guide them in learning a novel functional action. In the hands occupied condition, the rationality principle is sufficient to form a coherent interpretation of the situation; however, this is not the case in the hands free condition. Thus, observers will search for alternative explanations. The communicative nature of the demonstration will induce the presumption of relevance leading them to interpret the specific behavior manifested as relevant (from some -unspecified – functional point of view) and so it should be acquired. Because of this, besides construing of the final goal as “lighting the lamp”, infants will also construe as relevant a subgoal, which is to achieve this by making contact between the lamp and their forehead. This approach thus proposes that communication can enrich the encoding of the goal of the manner of action demonstrated with signaling the particular means (or features of it) as relevant to attain the final goal and this is being manifested as relevant information worth-to be learned. But is this process imitation at all?

A closer look at the performance of children could allow us to answer this question. It could be assumed that if children would turn to form-copying after observing a new, arbitrary, cognitively opaque action to attain a goal, they would apply imitation, and their strategy would be to merely copy the performed behavior. With respect to the head touch action, this strategy could imply that children would follow exclusively the head action as an opaque but successful way to bring about an effect, and would not use any other means towards the goal.

First, we analyzed the re-enactment behavior of children in relation to the goal object. We found that those children who performed the head action, not only performed this novel means action, but also performed the simpler (but undemonstrated) hand action as well to attain the goal, and did so without exception. The hand action in all cases preceded the head action, and was successful in bringing about the effect (Király et al, 2013). This means that children encoded the overall goal of the situation, and more importantly were inclined to try out alternative means that are effective in attaining it.

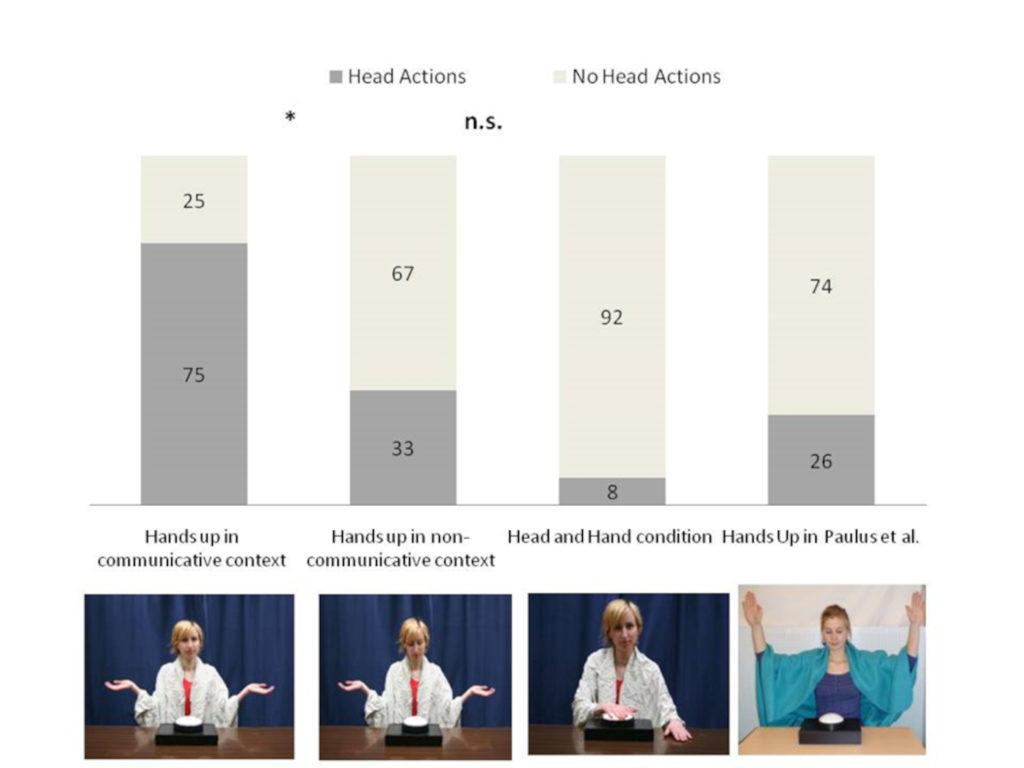

We compared the performance in the two conditions. The frequency of target action re-enactment was lower in the ‘Non-communicative observation context’ condition than it was in the ‘Communicative demonstration context’ (Fisher exact p = .05). Calculating the odd ratio confirmed (OR=5.431) that infants in the ‘Communicative context’ condition were more likely to re-enact the head action in comparison to the group of infants in the ‘Non-communicative context’ condition. Like in former studies (Gergely et al, 2002; Paulus et al. 2011), at least one hand action preceded the head action in 92 % of cases. The frequency of hand actions was 7.8 for one head touch within the first 60 seconds.

Interestingly, the head touches appeared in different forms in contrast to the modeled behavior [2]. Most importantly in 30 % of infants who performed the head action (3 infants in the Palms-in-air in communicative context and 1 infant in the Palms-in-air in Non- communicative context) lifted up the lamp to their heads instead of leaning forward to it. Moreover, altogether in 30 % of cases there was no contact between the approaching head and lamp (2 infants lifted up the lamp to the head but did not contacted it, the other 2 infants bend forward but did not make contact with the lamp in the Hands up in communicative context condition). These results confirm that infants performed voluntarily chosen variations of the originally observed behavior, rather than re-enacting a matching motor replica of the observed action. The selective pattern of results in the different demonstration conditions provide further empirical evidence for the natural pedagogy account of learning (Gergely & Csibra, 2005, 2006), namely, that the presence of the demonstrator’s ostensive and referential communicative signals addressing the infant, is a critical factor that is necessary to induce the imitative re-enactment of the novel – though apparently sub-efficient - means action.

Study 2: Situating the goal in context - the ‘balls’ study

The main objective of this study is to demonstrate that ostension plays a crucial role in linking the overall goal with the manifested sub-goals by integrating them relying on the relevant aspects of the manifested action context. Furthermore, we also aimed to show that ostensive demonstration of opaque means actions of an instrumental transitive act can induce variability in the produced action alternatives to reproduce the opaque sub-goal manifested. We would like to highlight the role of ostensive communicative and temporal parsing cues that could guide infants’ interpretive inferences to identify the relevant and new information that was manifested to them given the relevant aspects of the demonstrated action context.

In the ‘balls’ condition of Paulus et al. there were two softballs lying on the table next to the lamp. In the demonstration context preceding the manifestation of the opaque means action, the experimenter, after taking a seat, started to play with the two softballs for approximately 8 seconds. Then the experimenter keeping one softball in each hand put her hands on the table next to the lamp. From here on, the procedure followed exactly that of the ‘hands free’ condition of Gergely et al. with the only difference that the experimenter was holding the two softballs in her hands on the table while performing the opaque head action to light the lamp.

In this condition, one can also argue that observing the hand action itself (putting the hands with balls on the table) may not be sufficient to infer whether the hands are free or occupied. Such an inference must rely on and is constrained by the relevant aspects of the context in which the hand actions were demonstrated: The model was playing with the balls but now she stopped, from which infants may infer that her hands are now free to act (they don’t have to hold the balls).

Nevertheless, to clearly disambiguate the interpretation of the relevant action we introduced two different versions of the demonstration context in order to help infants to parse and interpret the manifested action sequence. In the ’Hands free keeping balls ‘condition we followed exactly the procedure of the ‘Balls’ condition used by Paulus et al.’s study, except that 1. the two balls were lying on two little plates next to the table, and 2. after the model put her hands with the balls next to the light-box, she lifted her hands up without the balls for 2-3 seconds. The balls remained in the plates and could not roll away. Then the model put her hands down again grasping the balls on the plates as before. After this short event, the model performed the head action with her hands resting on the table, keeping balls. In this context it was made explicit during the demonstration that the hands were free to act as they were not occupied with holding the balls so that hey wouldn’t roll away. In the Hands occupied with balls’ condition there were no plates next to the light-box, and the model performed the very same action sequence like in the ‘Hands free keeping balls’ condition. So, when she lifted up her hands for a while, the balls started to roll away, so she had to quickly reach back and grasp them again to keep them from rolling away. This situation, therefore, unambiguously manifested that the hands were occupied and were not free to engage in another action. In both situations, however, the model’s hands (with the balls in them) were placed on the table and so they could provided support for her body when she bent forward to touch the lamp with her head. So, according to the motor resonance theory or other versions of the automatic behavior-copying models there should be no difference in the amount of imitators in the two conditions. In contrast, the different situational constraints demonstrated relevant contextual information for the infant to infer whether the hands were free or occupied during the performance of the head touch action. This allowed the infants to interpret the head action as an efficient means to perform in the condition in which the hands were occupied with holding the ball. In contrast, given the relevant contextual information demonstrating that the hands were free (and could have been used to touch the lamp), infants could infer the demonstrated relevance manifested by performing the sub-efficient and so causally opaque head-touch action. This predicts that the amount of imitators should differ in the two conditions.

Method

Participants

Thirty 14-month-old infants were recruited (three of them were excluded from the final sample because of fussiness (n = 1), technical error (n=1), and parental inference (n=1). Participants were randomly assigned to two experimental conditions, as a result finally 14 infants were tested in hands free keeping balls condition and 13 infants were tested in the hands occupied with balls condition.

Test phase. The test phase followed the modeling phase immediately in both conditions. The model pushed the lamp across the table in front of the infants, and told ‘It is your turn now! You can try it!’ She encouraged the infant to play with it and stayed in the room. Infants were given 60 seconds to play with and explore the lamp.

Data analysis and scoring

The video records of the test phase were scored by two independent observers who were uninformed as to which of the conditions the participant belonged to. The dependent measure was whether the infant attempted to perform the head-on-box action within a 60 s time window (like in study 1). The two coders' evaluation of the participants' performance was in 92 % agreement (Kappa = 0.85).

Results

Number and proportion of infants who performed the target action are presented in Table 2.

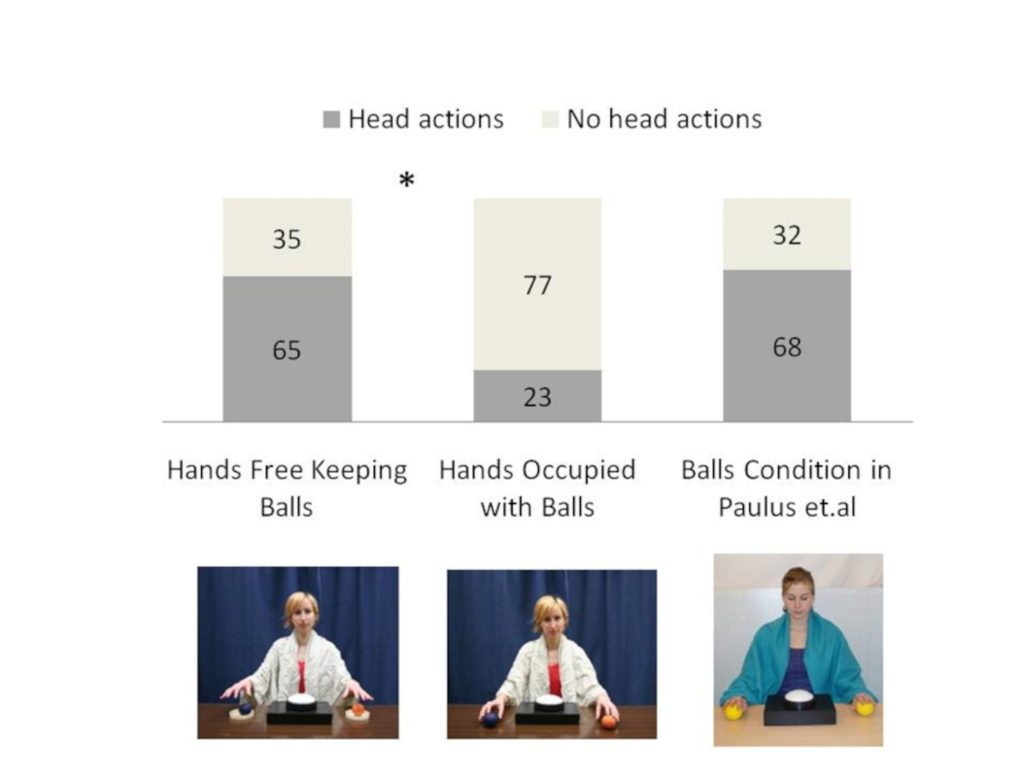

We compared the performance in the two conditions to each other and it was revealed that the frequency of target action was lower in the ‘Hand occupied with balls’ condition than it was in the ‘Hands free keeping balls’ condition (Fisher exact p = .054).; Odd ratio (OR=5,177) examination revealed that the probability of performing a head touch is more likely in the ‘Hands free keeping balls’ than in the ‘Hand occupied with balls’ condition.

Hand actions preceded head action in 94 % of cases. The frequency of hand actions was almost 6 hand action for a head touch. Moreover, like in study 1, the head touches did not follow the modeled head touch with high fidelity: intriguingly, in 50 % of the cases infants lifted up the lamp to their heads instead of leaning forward to it (4 infants in the Hands Free keeping balls condition and 2 infants in the Hands Occupied with balls performed the head action this way). Also in 58 % of cases (out of which 25 % - 3 infants were lifters) there was no contact between the approaching head and the lamp.

Study 3. Control condition:

Ostensive demonstration of both the opaque Head-Action and the transparent Hand-Action as the means to illuminate the lamp.

Our main suggestion is that when children observe in a communicative context the ostensive demonstration of a novel sub-efficient goal-directed means action that cannot be justified as efficient by invoking the principle of rationality, they will interpret it as a causally opaque sub-goal that represents a socially relevant manner to attain the final goal in the demonstrated context. However, in the present experiment we explore the further assumption that when children have already acquired an efficient (causally transparent) means action to operate an artifact (which is therefore not novel to them), they will not learn to re-enact an alternative non-efficient (and so causally opaque) means action to achieve the same goal, even if it is presented in an ostensive communicative context (Pinkham & Jaswal, 2011).

Method

Participants

Fourteen infants (14-month-olds) were tested in the Head and Hand Control Condition.

Apparatus

The apparatus used was identical to that of Study 1.

Procedure

Modeling phase. Here the model demonstrated two actions (in ostensive-communicative context), while she also demonstrated that her hands were free (lying on the table next to the box with the lamp). This condition thus was exactly the same as the ‘hands-free’ condition of Gergely et al (2002), with the only difference that here the model demonstrated the prepotent hand action as well, and both actions resulted in lighting up the magic lamp. The Head action was identical to the one employed in the previous experiments, while the Hand action consisted of touching the top of the lamp, and lighting it up, by hand. Both actions were modeled twice, in alternating order, with the first action counterbalanced across participants.

Test phase. The test phase in this condition was similar to the test phase of the communicative context condition of Study 1.

Results

Briefly, in the ‘Head and Hand’ condition only 8 % of infants (1 child) imitated the head touch (see Table 1). We compared the results of the present study to the results of the two conditions of Study 1. The frequency of target action re-enactment was lower in the ‘Head and Hand’ condition than it was in the Hands up in Communicative context’ condition of Study 1 (Fisher exact p = .001 , OR=48,1), and the frequency of target actions did not differ significantly in the ‘Hands up-in Non-communicative context’ condition of Study 1 and in the ‘Head and Hand' condition (Fisher exact p =.148).

Discussion

The results of the ‘Head and Hand’ condition is in line with the assumption of inference-based learning: infants were ostensively demonstrated that the efficient hand action is an established, socially sanctioned, and efficient way to attain the goal, therefore, they acquired this means action which they could judge as both efficient and socially shared and relevant. At the same time, they also saw an ostensive manifestation of an opaque alternative way (the head action) to attain the same goal. Since infants were demonstrated that both of the presented means (hand action and head action) are equally relevant and socially sanctioned way to attain the same goal, they were free to choose between them. The results show that in this case they chose to perform the more efficient and socially acceptable means action, and did not re-enact the opaque (sub-efficient and so more costly) alternative available. Note that this finding is hard to reconcile with theories according to which “children imitate behavior that is causally opaque with higher fidelity than behavior that has a transparent physical causal mechanism (Legare et al. 2015).” Also, the lack of imitation of the opaque head-action in the present study is also hard to explain by the variety of theories of cultural transmission that consider opacity of cultural actions as automatically inducing high-fidelity behavior-copying (e.g., Tennie et al., 2009).

Conclusions

According to our interpretation of inference-based selective imitation infants do not automatically produce a matching motor program generating high-fidelity behavioral replicas of the modeled action, or in other words, they do not engage in automatic motor behavior copying. Instead they encode the goal of the action in the given situation and they retrieve a behavior that is effective in its attainment. In addition, it is proposed that natural pedagogy modulates what is learned in the situation (Gergely & Csibra, 2005, 2009, Király, Csibra & Gergely, 2013): Ostensive communicative demonstrations can enrich the encoding of the goal by manifesting the particular means (or features of it) as a culturally relevant manner to attain the goal indicating to the infant that the manifested action variant is worth to be acquired. The presumption of relevance also induces infants attention to the contextual factors in which the action variant is manifested and induces in children to generate emulative variants to discover whether there is space for behavior refinement or not at the same time leading them to differentiate instrumental from conventional functions that are served and determine the action form used for goal-attainment.

Indeed, in our view, to provide an adequate explanatory model of the role of imitative re-enactment in human cultural learning, any viable theory must be able to account for two significant empirical properties of the way human infants acquire novel skills from observing them performed by others in their social environment. The first problem is how to account for the remarkable species-unique ability that makes even pre-verbal infants capable of fast-learning, long-term retention and delayed (but functionally appropriate) re-enactment of novel means actions observed even in cases when the new functional skill had been presented to them only on a single occasion and it’s re-enactment takes place a week (or, even months) later (as demonstrated e.g. by Meltzoff’s, 1988, 1996).

Second, it is crucial to account for (let alone predict) the adaptive ability of human infants (and more widely, of ‘human cultural novices’) to flexibly but appropriately generalize and selectively reproduce the newly acquired motor skill across a variety of functionally relevant novel contexts. The proposed inference-based account can provide solutions for the above two problems, since infants – as demonstrated in our studies – can encode a novel behavior after only several demonstrations; furthermore our study provided evidence demonstrating infants’ functionally appropriate generalization of the ‘head-touch’ action across different new token items belonging to the same artifact kind. These properties of inference-based selective imitative learning, however, represent challenges for behavior copying models of imitative learning to account for.

In sum, based on our results we argue that action re-enactment by the observational learner is not achieved by an automatic behavior copying mechanism but by an emulative action reconstruction process. It is important to emphasize, that though we refer to the phenomenon of social learning of novel actions by the term ‘imitation’ (emphasizing the fact that infants learn a specific type of new means-action observed to attain the goal), we use this term in a rather broad sense: a closer look at the concrete form of re-enacted target actions uncovered that the action means were reproduced by the infants in a remarkably flexible manner freely generating alternative action variants. Infants did not always bend forward and contacted the lamp with their forehead, rather they either lifted the lamp up by hand or bend forward to approach the lamp with the head. Moreover, in lots of cases (30 % in Study 1 and 58 % in Study 2, respectively) infants did not bring about the outcome but they ‘reinstated’ the observed goal. Hence, the main findings of the presented studies support the view that action understanding and goal inferences precede, rather than follow from, action mirroring processes (Csibra, 2007).

Communicative demonstrations of opaque actions induce and constrain production of alternative variants and thereby contribute to innovation both in the domain of actions serving instrumental functions and in the domain of conventional actions serving social functions

The role of ostension is to highlight a behavior, or aspect of behavior that is not accessible for the observer, it is not analyzable by the individual’s toolkit, however the ostensive demonstration induces the reproduction of behavior, while allowing variability in this reproduction. Indeed, the ostensive demonstration brings into focus aspects of the novel action sequence to be encoded as subgoals that are otherwise would remain opaque, or unattended. These subgoals are highlighted within specific contexts that could help to ground their relevance, however as being goals could also be attained through variable action means. That results in the fact that some sub-efficient means action does not overwrite or rule out other versions, but rather often co-exists with other more efficient variants that are also acceptable in every-day situations.

Our head-touch studies underline that the sub-efficient action means are used together with the efficient alternatives. The context of teaching, the ostensive demonstration not only induce the encoding of a relevant, novel aspect of behavior as a subgoal, but also allows segmentation and analysis of the situation in order to promote learning about the specific contexts in which the novel action means could be applied as relevant.

Alternations in contexts thus could also be responsible for variability of behavior, and at the same time could contribute to the survival of both the efficient and sub-efficient but socially determined, conventional formats, and the application of these formats in a context- dependent way.

How and why do the less efficient, cultural versions survive? First, as seen in our illustrative head touch studies, children try out the attainment of the goal, varying the means in a trial and error form. This process could result in flexibility, through the comparison of alternative attainment formats, including the versions tried out for attaining the subgoal itself (see as an example the versions applied to contact the lamp with different parts of the head). The potential monitoring of the variations and their success during re-enactment and relating them to different features of the context in which they tend to be produced could also facilitate and lead to the emergence of new variants and combinations of behavior. This process could also result in a deeper, and more detailed understanding of the different kinds of functional determinants that are involved in relating the sub-goal and the goal in particular contexts. In particular, by comparing and analyzing the alternative variants produced along the lines of efficiency and relating them to differences of the situational context in which they are more likely to appear, the learner could differentiate the relevant contributions of causal and social conventional functions to the use of the alternative action variants to achieve the subgoal. Consequently, during the reproduction of the behavior in a context-dependent way new variants could emerge. These new variants could result in new solutions for problems and so could also serve innovative processes.

If the rule would be to copy blindly that is opaque, there would be no room for instrumental refinement. Even in the case of subgoals encoded as conventional, cultural versions of manners, this learning process would introduce variability, and could therefore allow the emergence of more efficient alternatives. We propose that the intermittent ostensive demonstrations of the causally opaque sub-efficient actions to attain sub-goals in certain types of social contexts function to maintain and stabilize the normative use of less efficient versions and to save-guard against their disappearance from the cultural repertoire due to the discovery and successful use of more efficient alternatives in a wider range of functionally similar instrumental contexts. Such intermittently administered ostensive ‘injections’ highlight that the utilization of a subefficient action version is not accidental, but serves a social function which constitutes a culturally sanctioned manner alternative. This picture thus suggests that ostensive demonstration of opaque action variants induces in the cultural learner a presumption of relevance and leads to relevance-based emulation of alternative variants. This source of reproductive variability in the domain of instrumental actions could foster the emergence of technological innovations by discovering more adaptive action variants or their combinations and generalizing the acquired functional skill over a broad range of contexts.

References

Buchsbaum D, Gopnik A, Griffiths TL, Shafto P. (2011). Children's imitation of causal action sequences is influenced by statistical and pedagogical evidence. Cognition, 120(3), 331-40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.12.001

Carpenter M, Call J, Tomasello M. (2005). Twelve- and 18-month-olds copy actions in terms of goals. Developmental Science, 8(1), F13-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00385.x

Chen, M., Király. I. Gergely, G. (2012) : Opacity and Relevance in Social Cultural Learning: Relevance-Guided Emulation in 14-Month-Olds paper presented at Budapest CEU Conference on Cognitive Development, Budapest, January 12-14.

Clegg, J.H., Legare, C.H. (2016) Instrumental and conventional interpretations of behavior are associated with distinct outcomes in early childhood. Child Development 87 (2), 527-542.

Csibra, G. (2007). Action mirroring and action understanding: an alternative account. In: P. Haggard, Y. Rosetti, & M. Kawato (Eds.), Sensorimotor Foundations of Higher Cognition. Attention and Performance XXII. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 435-458.

Csibra, G. & Gergely, G. (2006). Social learning and social cognition: The case for pedagogy. In Y. Munakata & M. H. Johnson (Eds.), Processes of Change in Brain and Cognitive Development. Attention and Performance XXI (249-274). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Csibra, G. & Gergely, G. (2009). Natural Pedagogy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13, 4, 148-153.

Csibra, G., Gergely, G. (2011). Natural pedagogy as evolutionary adaptation. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 12; 366 (1567), 1149-57. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0319

Gergely, G. (2007). The social construction of the subjective self: The role of affect-mirroring, markedness, and ostensive communication in self-development. In L. Mayes, P. Fonagy, & M. Target (Eds.), Developments in psychoanalysis. Developmental science and psychoanalysis: Integration and innovation (45–88). Karnac Books.

Gergely, G. and Csibra, G. (2003). Teleological reasoning in infancy: The naive theory of rational action. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7, 287-292.

Gergely, G., & Csibra, G. (2006). Sylvia’s recipe: The role of imitation and pedagogy in the transmission of human culture. In: N.J. Enfield & S.C. Levinson (Eds.), Roots of Human Sociality: Culture, Cognition, and Human Interaction (229-255). Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Gergely, G., Bekkering, H., & Király, I. (2002). Rational imitation in preverbal infants. Nature, Vol. 415, 755.

Gergely, Gy. Jacob, P. (2012). Reasoning about Instrumental and Communicative Agency in Human Infancy. In F. Xu & T. Kushnir. Eds. Rational Constructivism in Cognitive Development, Academic Press, 59-94.

Kapitány R, Nielsen M. (2019). Ritualized objects: how we perceive and respond to causally opaque and goal demoted action. J. Cogn. Culture, 19, 170-194. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685373-12340053.

Király, I., Csibra, G., & Gergely, G. (2013). Beyond rational imitation: learning arbitrary means actions from communicative demonstrations. Journal of experimental child psychology, 116(2), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.12.003

Legare, C.H. (2019) The Development of Cumulative Cultural Learning. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1:1, 119-147.

Legare, C.H., Nielsen, M. (2015), Imitation and innovation: The dual engines of cultural learning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(11), 688-699.

Legare, C.H., Wen, N-J., Herrmann, P.A., Whitehouse, H. (2015). Imitative flexibility and the development of cultural learning. Cognition 142, 351-361.

Legare, Cristine H. and Nielsen, Mark (2020). Ritual explained: interdisciplinary answers to Tinbergen's four questions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 375 (1805) 20190419 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0419

McGuigan, N., Whiten, A., Flynn, E., & Horner, V. (2007). Imitation of causally opaque versus causally transparent tool use by 3- and 5-year-old children. Cognitive Development, 22(3), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.01.001

Meltzoff, A. N. (1988). Infant imitation after a one week delay: Long term memory for Novel acts and multiple stimuli. Developmental Psychology, 24, 470-476.

Meltzoff, A. N. (1996). The human infant as imitative generalist: A 20-year progress report on infant imitation with implications for comparative psychology. In C. M. Heyes & B. G. Galef, (Eds). Social learning in animals: The roots of culture, 347-370. NY: Academic Press.

Over H, Carpenter M. (2012) Putting the social into social learning: explaining both selectivity and fidelity in children's copying behavior. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 126(2), 182-92. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024555.

Over, H. and Carpenter, M. (2013), The Social Side of Imitation. Child Development Perspectives, 7: 6-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12006

Paulus, M., Hunnius, S., Vissers, M., & Bekkering, H. (2011). Imitation in infancy: Rational or motor resonance? Child Development, 82, 1047-1057.

Pinkham, A. M., & Jaswal, V. K. (2011). Watch and learn? Infants privilege efficiency over pedagogy during imitative learning. Infancy, 16, 535-544

Rendell, L. Fogarty, L., Hoppitt, W.J., Morgan, T.J., Webster M.M., Laland, K.N. (2011). Cognitive culture: theoretical and empirical insights into social learning strategies. Trends in Cognitive Science, 15(2), 68-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.12.002

Tennie C, van Schaik CP. (2020). Spontaneous (minimal) ritual in non-human great apes? Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 375: 20190423.

Tennie, C., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2009). Ratcheting up the ratchet: on the evolution of cumulative culture. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 364(1528), 2405–2415. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0052

Toelch, U., Bach, D. R., & Dolan, R. J. (2014). The neural underpinnings of an optimal exploitation of social information under uncertainty. Social cognitive and affective neuroscience, 9(11), 1746–1753. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst173

Tomasello, M. (1999). The Cultural Origins of Human Cognition. Cambridge, MA.

Tomasello, M., Carpenter, M., Call, J., Behne, T., & Moll, H. (2005). Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 675-735.

Watson-Jones, R.E., Legare, C.H. (2016).The social functions of group rituals. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(1), 42-46.

Wen, N.J., Herrmann, P.A., Legare, C.H. (2016). Ritual increases children’s affiliation with in-group members. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(1), 54-60.

Wohlschläger, A., Bekkering, H., & Gattis, M. (2003). Action generation and action perception in imitation: An instantiation of the ideomotor principle. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: Biological Sciences, 358, 501-515.

[1] Note that according to this account infants’ re-enactment of the head-touch action may not – and need not – involve the production of a faithful motor ‘copy’ of the ‘head touch without hand support’ action of the model. Infants may have to emulate the demonstrated goal of contacting the lamp with the head in so far as they – unlike the model – may need to use their hands to support their body during the re-enacted head touch action.

[2] This chance observation could have occurred because the Velcro we used here to mount the lamp on the box was somewhat weaker than the earlier used one, so infants could lift up the lamp if they wanted to.

Dan Sperber 18 December 2020 (00:53)

Beyond infancy

I believe yours is a major contribution to our overall common project: It makes manifest not just how useful but even how necessary it is to consider in depth the individual and inter-individual psychological processes involved at each micro-step in chains of cultural transmission. You take us, for instance, way beyond the (still useful) imitation vs emulation distinction. There is much to think about and to discuss in your positive proposal and in the new evidence you provide for it but, at this time, I just want to point to one issue which is relatively peripheral to your main point but is central to clarifying the relevance of your contribution to our joint project.

Your empirical research is on infants. This makes it of obvious relevance to our general understanding of human psychology. Its precise relevance to cultural transmission, in particular of techniques, need to be clarified, however. Different cultural techniques are acquired at different ages, mostly in middle to late childhood or even in adulthood. One possibility is that what happens then is just – or at least is centrally – a development of what you describe as taking place in infancy. Another possibility is that different learning procedures are acquired in the process of cognitive development and that the transmission of various techniques is staggered by the timing and order of acquisition of these learning procedures. These learning procedures themselves are likely to exploit both evolved cognitive dispositions and cultural developed resources in various combinations. A plausible view is that natural pedagogy (and, more broadly, ostensive communication and the presumption of relevance it elicits) is one of these evolved disposition and one that plays a central role in most if not all later-acquired learning procedures.

To put the issue in the simplest terms: to what extent and how can we and should we take advantage of your ground-breaking research on the role of ostension in infants acquisition of cultural knowledge when studying the transmission of a variety of techniques, a transmission that, in most cases, takes place well after infancy?