- Technical Flexibility and Rigidity Webinar (private)

Week 12 – Stasis? A developmental perspective on rigidity of transmission and flexibility in use of techniques in Early Stone Age

This early draft was authored by Miriam Noël Haidle.

[Preliminary remark: The following text is a sketch. The parts in italics provide only some notes which have to be further developed.]

Introduction

Studying the rigidity of transmission and the flexibility in use of techniques in Paleolithic times is somewhat limited, even more so if you concentrate on the first three million years of human cultural evolution. The first artefacts ascribed to hominins are stones that have been manipulated in two different ways, with the passive-hammer respectively the bipolar technique, probably to produce pieces with cutting edges which could be used, for example, to dissect a carcass (Harmand et al. 2015; Lewis & Harmand 2016). The archaeological assemblage from Lomekwi, Kenya has been dated to 3.3 Ma (million years before present), but doubts have been raised if this age is the correct one (Dominguez-Rodrigo & Alcalá 2019; Archer et al. 2020). A time gap of around 700,000 years (or around 35,000 generations) without any cultural remains separates the find-bearing stratum at Lomekwi from the next-younger evidence of hominin tool behavior. BD 1 at Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia (Braun et al. 2019a, b; Sahle & Gossa 2019), the sites EG10 and 12, OGS 6 and 7 at Gona, Ethiopia (Semaw et al. 1997; 2003; 2009; de Lumley et al. 2018) are dated to 2.6–2.5 Ma. Only 150,000 to 250,000 years later is the dating of three other sites, A.L. 666 and 894 at Hadar, Ethiopia (~2.35 Ma; Hovers 2012; Goldmann & Hovers 2012) and Lokalelei 2C, Kenya (2.34 Ma; Delagnes & Roche 2005). Sites with traces of human action, of the manufacture of stone artefacts and their use and an unquestioned dating older than two million years can be counted on two hands and are limited to the African continent.

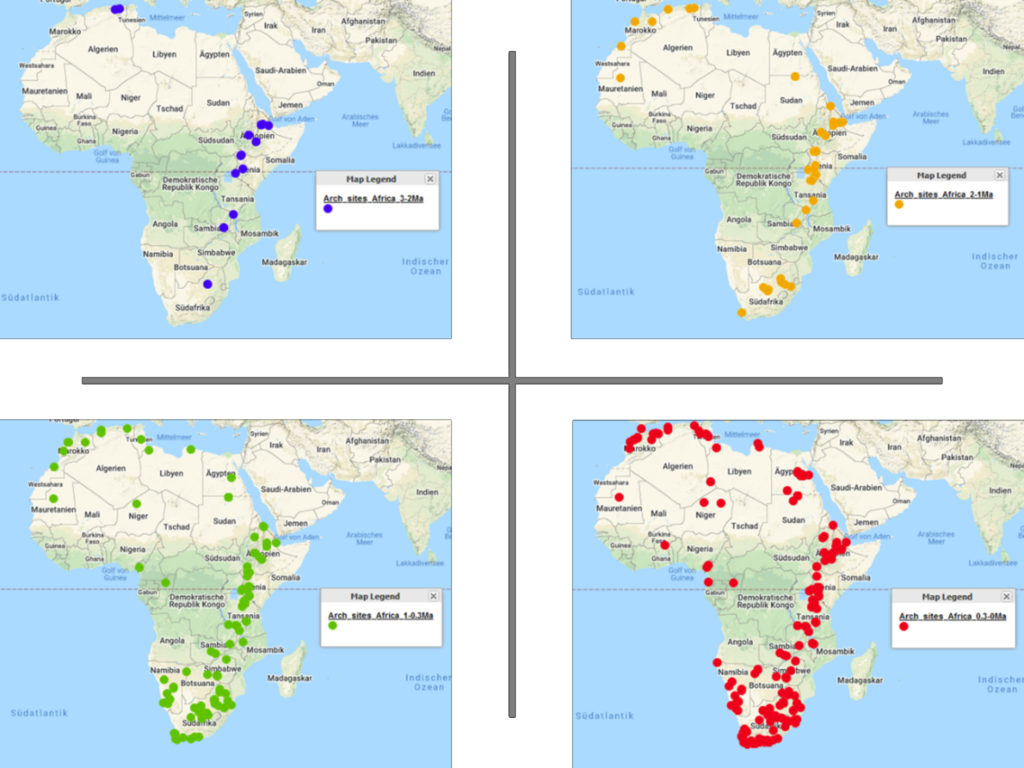

The maps in Fig. 1 show the frequency and distribution of archaeological sites in Africa in different time slices, with the assemblages of the last 300,000 years by far outnumbering the assemblages of the previous 3 million years. If we look at these first 3 million years of cultural evolution, we see at a rough estimate one site per 1000 generations. This data coverage cannot allow more than a glimpse on the rigidity of transmission and the flexibility of use of techniques in the early phases of human cultural evolution. The prerequisites of a manifestation of behavioral patterns in material products, their embedding, preservation over thousands of years, discovery by a knowledgeable person and an adequate interpretation impose further constraints on the archaeological record of past activities. Stones with clear signs of manipulation such as the manufacture of cutting edges by flaking are therefore in the center of archaeological attention. Only recently, simpler tools with traces of percussion activities have got into focus (Arroyo & de la Torre 2016; 2018; Arroyo et al. 2020; Assaf et al. 2020). The use of tools made from organic material, which are widely known from current great apes, is assumed but can hardly be studied due to the lack of evidence. To get an impression what we may miss, some numbers on the tool use of our closest living relatives can help. A compilation of tool behavior of orangutans counted in 2009 more than 40 different performances with tools in at least six contexts, with 29 tool types out of nine raw materials, some of them manufactured intentionally (Schuster 2009). For chimpanzees more than 90 different performances with tools have been counted in 2009 (Stolarczyck 2015). More than 13 different tool types out of 17 raw materials have been applied in at least twelve contexts. Chimpanzees modify the raw materials in various ways to produce tools adequate for a specific purpose and use different tools in a sequential way on one problem. They apply wooden implements in hunt as well as for digging up roots and tubers. And the evidence has been growing since.

So, is studying the rigidity of transmission and the flexibility in use of techniques in Paleolithic times a hopeless endeavor? Hope for a detailed empirical examination does not exist. But studying the Paleolithic record is nevertheless worthwhile to gain insight into developmental aspects of transmission and use of techniques. The lack of evidence forces us to have a close look to current daily routines of humans and the variation within, because what we can expect in the early phases of human cultural evolution are rather simple daily routines. Then we can contrast these observations with comparable situations in great apes to get an impression about a minimum range of the variability in transmission and use of techniques in hominins. In a next step, a developmental track can be sketched that can be strengthened by archaeological evidence. The result will remain a sketch, but a well-informed one.

Human daily routines in transmission and use of techniques – an example

When you start to learn cooking, you stick accurately to the list of ingredients and the detailed instructions of your teacher or the recipe. When you are used to prepare meals but want to try a new dish, you take the list of ingredients and follow neatly only those instructions, which are unfamiliar to you. The habitual parts (how to slice something, how to stir something, when to stop kneading a dough) you accommodate from your experience to the current requirements. After replicating the process a few times, you probably start to vary the recipe regarding the ingredients and the activities according to your ideas. After varying the whole performance for some time, the most preferred variant crystallizes, which is the one you will transmit to others. When you prepare a traditional meal of your family for a feast day, however, you adhere closely to the original recipe due to social pressure of your kin. It is not important whether you like it, if it is complicated or if you normally use much more efficient utensils. Preparing this meal in exactly the way as it was transmitted tenses the links to and within your group.

The cooking example reveals several things which will become important in this contribution. First, techniques are no clear-cut entities but an assemblage of a range of knowledge and skills. Then, their transmission and use are developing in a certain time-depth that can span from few minutes to years. In these processes, techniques can become embodied. Finally, the performances of learning and applying a technique are embedded in an environmental context and situated, depending on the current setting of needs and availability of material, mental, and social resources. The transmission of knowledge and skills as well as techniques of tool manufacture and use are, at least in humans, cultural performances. As such, three interdependent dimensions can be assumed for their development – evolutionary-biological, historical-social and ontogenetic-individual – interacting with a dynamically changing specific environment (Haidle et al. 2015).

Techniques – from problem to solution?

From a general view, techniques can simply be seen as a sequence of activities in interaction with parts of the specific environment to reach a certain aim. And here our observations already become tricky. What makes a problem or a need, what defines an adequate solution, and what elements constitute a technique? In the archaeological context, techniques associated with a tool refer to its manufacture and use. The general problem-solution concept as well as the material, form and functionality of a tool are vital parts of a technique. They correspond to some degree to activities and means to produce and apply it to a range of objectives in a more or less limited environmental, social, and cultural context, all of which also contribute to the technique (cf. Haidle & Bräuer 2011). Stout (2002) highlighted various aspects and the complexity of their relations in an ethnographic example. He described the production of stone adzes among the Langda of Irian Jaya as a phenomenon characterized as much by social relations and norms and mythic significance as by specific reduction strategies and technical terminology.

Techniques generally represent multifactorial traits. They are composed of material affordances and constraints, of habitual aspects such as preferences, rhythms, directions. They include background and specific knowledge as well as actions. The parameters of a technique may be operated by an individual, in a joint activity of several individuals or in complementary activities. The set of elements of a technique overlaps with those of other techniques, and they are integrated in a meshwork of cultural relations. Depending on all those factors, the elements and the entireties of the techniques (knowledge, skills, habits) may vary markedly and thus the potentially transmitted entities. These may range from perspectives and preferences via sequential ordering, spatial organization and specific movements to contextual classification and superordinate sense.

Flexible use of techniques

The ways how a technique is applied depends on the familiarity with the elements of the technique. Starting to learn a new technique is a strenuous endeavor. Only a certain number of unknown elements can be managed at once. An individual will try to reduce the variables until she gets habituated to some aspects; then new steps can be included. After learning how to open eggs, how to apply salt and pepper to flavor a meal and how to manage the cooker, my son is now learning how to integrate all this in frying eggs and bacon in a pan. The less an individual can overlook the whole process because of the number of elements or their opaqueness, the more she sticks to parts that can be grasped and accomplished. When parts of the technique or the whole process have been acquired, the frequency and the variability of the settings of their application determines the grade of expert cognition. The standard behavior is set for standard circumstances and is largely embodied; only deviant situations require special attention and an adjusted performance.

With an increase of the variable elements of a technique, the potential variability and flexibility in use augment. If you have only salt to add to your cabbage, the potential flexibility in flavoring your dish is much lower than if you have pepper, chili, curry, and herbs available to spice different vegetables. The potential variability and flexibility are restricted, however, by how many related factors will be affected and how much. For example, if variants are very time-consuming, arduous or need another person’s support, their application will be more constrained in favor of simpler ones. But if a technique is part of a meaningful system such as a specific activity in a religious liturgy, simplifying this technique can spoil the whole rite and its impact.

A developmental perspective on flexibility in the use of techniques

Three interdependent dimensions of development – an evolutionary-biological, a historical-social, and an ontogenetic-individual, interacting with the specific functional environment – affect the flexibility in the use of techniques (cf. Haidle et al. 2015). The evolutionary-biological dimension expresses the genetically assigned range of the anatomical structure and the physiological processes determining the baseline of a species behavior, cognitive competences, and emotions. In the case of flexible use of techniques, this dimension has impact on the general physical and mental structures of our species that delineate the range of possible interactions with the environment. The paws of sea otters allow only very limited interactions with tools compared to the long-fingered hands of chimpanzees, and even more to short-fingered hands with opposable thumbs as humans possess.

Within the genetically inherited range, a human individual unfolds techniques in an ontogenetic-individual dimension based on ongoing personal experiences with the specific social and material environment. Taking the cooking example, we have seen one of the possible ways of acquirement of associated knowledge and skills, phases of getting familiar with basic elements, of extending the applications, of reducing the range to the common ones. While at a young age flexibility in use of a technique may be restricted by lacking experience with several of its elements but fostered by curiosity, at an older age flexibility may be limited due to habituation to one variant or increased through variegated experiences.

Between the long phylogenetic track and the individual lifetime, the historical-social as the third dimension plays a vital part in the development of the human use of techniques. Group members influence the performances of an individual by being models, providing information about beneficial or unfavorable aspects, and tolerating a range of variants. Techniques common in a group can be transmitted for some time like a vogue or over generations and become long-lasting traditions. How to prepare a meal is very group specific, with communal entities ranging from supraregions and regions to villages and families. The influence of the different group levels on the repertoire of meals an individual is regularly preparing and the techniques in doing so depends on the cohesion of the respective group and the individual experiences with realities outside.

The performances of individuals and groups are based on their specific environment. This comprises the material and immaterial resources that can be exploited, the available tools, other competing or assisting actors, the possible relationships between the elements of the specific environment and the subject, and the time depths in which interactions with these elements can be perceived and realized. The specific environment is shaped by abiotic factors such as climate, other species requirements and activities, and to a large extent the performances of each member of a group. The different human ways to prepare a meal depend, among others, on the plants and animals available, the implements and facilities to process them, semi-finished products or labor provided by other individuals, and the time that can be spent to make provisions and actually execute it.

These three developmental dimensions are interdependent and interact with the specific environment. The performance of an individual is based on an evolutionary-biological development and is ontogenetic-individually unfolded, influenced by historical-social constraints and scaffolds. The historical-social setting provides a broader or narrower path for the ontogenetic-individual development, can allow loops or side-tracks or demand sticking to a short trail. The individual experiences can change the historical-social setting if they are shared with other group members. Thus, the historical-social dimension is formed and constantly reshaped by elements of performances of single actors. The group characteristics in their condensed form, however, reach beyond the sum of these elements, and at the same time, are much more limited in range. The performances of individuals act and react on a specific environment and transform it continuously through these interactions; they create a cultural niche (Laland & O’Brien 2011). And the specific environment forms the basis for developments in the evolutionary-biological dimension (for a more detailed discussion on different processes linking the dimensions see Haidle 2019, 134-136).

Forms of transmission – exclusive or complementary?

Aspects of behavior can be socially transmitted in several ways, which can be classified in two overarching groups: A) unidirectional-reproducing, including material engagement with products of the behavior of others, emulation, and imitiation, and B) bidirectional-participating, including co-performance, action coordination, and different forms of teaching (cf. Kline 2015; Gärdenfors & Högberg 2017). The transmission can be intentional by both, the learner and the expert, or one or none of them.

In the process of transmission of a performance or part of it, the different forms of transmission can be, and often are, mixed. An individual learns one aspect of a behavior via material engagement with the products of the behavior of others – what are the qualities of a hammer stone to open nuts, to take an example from the chimpanzees’ world. A second aspect can be acquired through emulation – somehow, a nutshell can be opened by using a hammer stone and reveals a tasty kernel. A third aspect – which nuts are palatable – and further aspects – what is the right rhythm and force for pounding – are transmitted by co-performance of choosing a common feeding tree and of creating the same sound in the opening process. Which type of transmission works, depends on the situation, the historical-social background of the performance, and the individual stage of learning and already acquired knowledge and skill. In humans, the mix of transmission forms and specific procedures can be very group specific as can be seen in types of intentional information transmission such as story-telling (Lipka 1991), gifting (Nishiaki 2013), and schooling (Maynes 1985; Engermann et al. 2009). Typical elements of structuring relationships affect the relation between experienced and unexperienced individuals and thus the course of transmission. This is reflected in different forms of master-apprentice relationships, ranging from collaborative groups of individuals with different levels of skills and knowledge (Stout 2002), or medieval maistre who “served as a companion, supervised behavior, gave advice” (Holmes 1968, 167) to the famous sushi master and his – for years – quietly observing student (Matsuzawa et al. 2001, 573).

Rigidity of transmission

Increase with social norms

Rigidity in the use of techniques, a limited range of variants, and controlled processes can be beneficial in several respects, for example 1) clearly defined product required > reduction of waste. 2) Multi-step process with many variables > reduction of choices. 3) Complex process with opaque elements > reduction of necessary understanding. In sum, reduction of costs (time, energy) in a rather closed system. Unfavorable in other respects: 1) context is very variable > goal not achieved. 2) Problem easier than assumed > shortcuts not possible.

A developmental perspective on the rigidity of transmission of techniques

All humans today share the same evolutionary-biological basis and, in principle, the same historical-social and individual-ontogenetic mechanisms to unfold the different forms of transmission. Although they share some features, each form of transmission has specific cognitive and contextual requirements. There is, for example, a biological basis of the cognitive ability for imitation (Huber et al. 2009; Whiten et al. 2009) enabling a more precise copy of behavioural processes. Imitation of a technique including a thing to operate with or to be manipulated as well as simple forms of teaching such as tool transfer entail triadic attention between the self, another human subject and an object and/or a tool (Tomasello 1999). Active action coordination and advanced forms of teaching additionally need shared attention and intentionality of both subjects (Tomasello & Moll 2010) facilitating a joint examination of a thing or process by several individuals. The different forms of transmission must not be treated as a developmental sequence but as complements.

Early Stone Age perspectives on transmission and use of techniques

In human evolution, the number of elements associated with interactions with the environment have continuously expanded. Looking at the repertoire of modern great apes, we can roughly appraise the probable range of performances of our early ancestors.

Sticks, twigs, blades of grass, strips of bark, leaves, moss, stones as tools and aids, single, in combination, or in a sequential set

Probe, pound, throw, dip, fish, scoop, wipe, fold, crush, rip, break, shape into brush, dig

Applied on the acting subject herself, on conspecifics, plants or plant parts, animals (prey, competitors, enemies), landscape features (ground, termite mounds, water pools, swamps) for different purposes: nutrition, defense, hygiene, display, aggression, exploration, locomotion, stimulation

Modular, composite, complementary, notional cultural capacities (Haidle et al. 2015; Löffler 2019)

Mechanisms of change in cultural capacities, including transmission and use of techniques: evolutionary-biological dimension - genetic mutation and selection, the latter of which is based on an interaction with the specific social (other individuals) and material environment. Ontogenetic-individual – epigenetics, individual learning, and invention. Historical-social – These two developmental dimensions interact with the environment and are, in different proportions, active in the development of the performances of all organisms. A third dimension, the historical-social dimension, comes into play in social organisms. Through being a model for performances of similar organisms, providing information about beneficial or unfavorable performances, and tolerating a range of variants of performances, members of the same group foster learning, group conformity, the establishment of traditions and their overcoming by innovations. Learning shifts from a purely individual to an increasingly interactive process with a focusing of the content.

References

Archer, W., Aldeias, V., & McPherron, S. P. (2020). What is ‘in situ’? A reply to Harmand et al. (2015). Journal of Human Evolution, 142, 102740.

Arroyo, A., & de la Torre, I. (2016). Assessing the function of pounding tools in the Early Stone Age: a microscopic approach to the analysis of percussive artefacts from Beds I and II, Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania). Journal of Archaeological Science, 74, 23-34.

Arroyo, A., & de la Torre, I. (2018). Pounding tools in HWK EE and EF-HR (Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania): Percussive activities in the Oldowan-Acheulean transition. Journal of Human Evolution, 120, 402-421.

Arroyo, A., Harmand, S., Roche, H., & Taylor, N. (2020). Searching for hidden activities: percussive tools from the Oldowan and Acheulean of West Turkana, Kenya (2.3–1.76 ma). Journal of Archaeological Science, 123, 105238

Assaf, E. 2019. Core sharing. The transmission of knowledge of stone tool knapping in the Lower Palaeolithic, Qesem Cave (Israel). Hunter Gatherer Research 3.3, 367-399.

Assaf, E., Barkai, R., & Gopher, A. (2016). Knowledge transmission and apprentice flint-knappers in the Acheulo-Yabrudian: A case study from Qesem Cave, Israel. Quaternary International 398, 70-85.

Assaf, E., Caricola, I., Gopher, A., Rosell, J., Blasco, R., Bar, O., ... & Cristiani, E. (2020). Shaped stone balls were used for bone marrow extraction at Lower Paleolithic Qesem Cave, Israel. Plos One, 15(4), e0230972.

Braun, D. R., Aldeias, V., Archer, W., Arrowsmith, J. R., Baraki, N., Campisano, C. J., ... & Feary, D. A. (2019a). Earliest known Oldowan artifacts at> 2.58 Ma from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia, highlight early technological diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(24), 11712-11717.

Braun, D. R., Aldeias, V., Archer, W., Arrowsmith, J. R., Baraki, N., Campisano, C. J., ... & Feary, D. A. (2019b). Reply to Sahle and Gossa: Technology and geochronology at the earliest known Oldowan site at Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(41), 20261-20262.

Dominguez-Rodrigo, M., & Alcalá. L. (2019). Pliocene Archaeology at Lomekwi 3? New Evidence Fuels More Skepticism. Journal of African Archaeology 17.2, 173-176.

Engerman, S. L., Mariscal, E.V., & Sokoloff, K. L. 2009. The evolution of schooling in the Americas, 1800-1925. In Eltis, D., Lewis, F.D., & Sokoloff, K. L. (eds.), Human capital and institutions: a long-run view. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 93-142.

Gärdenfors, P., & Högberg, A. 2017. The archaeology of teaching and the evolution of Homo docens. Current Anthropology 58/2, 188-208.

Goldman-Neuman, T., & Hovers, E. (2012). Raw material selectivity in late Pliocene Oldowan sites in the Makaamitalu Basin, Hadar, Ethiopia. Journal of Human Evolution, 62(3), 353-366.

Haidle, Miriam Noël (2019). The origin of cumulative culture—not a single-trait event, but multifactorial processes. In Overmann, K. A., Coolidge, F.L. (eds.), Squeezing minds from stones. Oxford University Press, New York, 128–148.

Haidle, Miriam Noël, Michael Bolus, Mark Collard, Nicholas J. Conard, Duilio Garofoli, Marlize Lombard, April Nowell, Claudio Tennie & Andrew Whiten 2015. The Nature of Culture: an eight-grade model for the evolution and expansion of cultural capacities in hominins and other animals. Journal of Anthropological Sciences 93, 43-70.

Haidle, Miriam Noël & Jürgen Bräuer 2011. Special Issue: Innovation and the Evolution of Human Behavior. From brainwave to tradition – How to detect innovations in tool behaviour. PaleoAnthropology 2011, 144-153.

Haidle, Miriam Noël, Oliver Schlaudt 2020. When does cumulative culture begin? A plea for a sociologically informed perspective. Biological Theory 15/3, 161-174.

Harmand, S., Lewis, J. E., Feibel, C. S., Lepre, C. J., Prat, S., Lenoble, A., ... & Taylor, N. (2015). 3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya. Nature, 521(7552), 310-315.

Holmes, U. T. (1968). Medieval Children. Journal of Social History, 2(2), 164-172.

Hovers, E. (2012). Invention, reinvention and innovation: the makings of Oldowan lithic technology. In Developments in Quaternary Sciences (Vol. 16, pp. 51-68). Elsevier.

Huber, L., Range, F., Voelkl, B., Szucsich, A., Virányi, Z., & Miklosi, A. 2009. The evolution of imitation: what do the capacities of non-human animals tell us about the mechanisms of imitation? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 364, 2299-2309.

Kline, M. A. 2015. How to learn about teaching: An evolutionary framework for the study of teaching behavior in humans and other animals. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 38, e31.

Laland, K. N., & O’Brien, M. J. (2011). Cultural niche construction: An introduction. Biological Theory 6(3), 191-202.

Lewis, J. E., & Harmand, S. (2016). An earlier origin for stone tool making: implications for cognitive evolution and the transition to Homo. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1698), 20150233.

Lipka, J. 1991. Towards a culturally based pedagogy: a case study of one Yup’ik Eskimo teacher. Anthropology & Education Quarterly 22/3, 203-223.

Matsuzawa, T., Biro, D., Humle, T., Inoue-Nakamura, N., Tonooka, R., Yamakoshi, G. 2001. Emergence of culture in wild chimpanzees: education by master-apprenticeship. In T. Matsuzawa (ed.), Primate origins of human cognition and behavior. Tokyo: Springer, 557-574.

Maynes, M. J. 1985. Schooling in Western Europe: A social history. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Moore, R. 2013. Social learning and teaching in chimpanzees. Biology & Philosophy 28/6, 879-901.

Nishiaki, Y., 2013. “Gifting” as a means of cultural transmission: the archaeological implications of bow-and-arrow technology in Papua New Guinea, in Dynamics of learning in Neanderthals and modern humans, Volume 1 Cultural Perspectives, eds. T. Akazawa, Y. Nishiaki & K. Aoki . Tokyo: Springer, 173-185.

Rogers, Everett M. 19954. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.

Sahle, Y., & Gossa, T. (2019). More data needed for claims about the earliest Oldowan artifacts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(41), 20259-20260.

Schuster, J. (2009). Das Werkzeugverhalten von Orang-Utans. Kognitive Variabilität, Flexibilität und Komplexität. Unpublished MA thesis, Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte und Archäologie des Mittelalters, Dep. Ältere Urgeschichte und Quartärökologie, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen.

Stolarczyk, R.E. (2015). Das Werkzeugverhalten der Schimpansen. Kognitive Variabilität, Flexibilität und Komplexität. Tübingen: tobiasLIB. http://hdl.handle.net/10900/67173

Stout, Dietrich 2002. Skill and cognition in stone tool production: an ethnographic case study from Irian Jaya. Current Anthropology 43/5, 693-722.

Tomasello, M., & Moll, H. 2010. The gap is social: Human shared intentionality and culture. In P.M. Kappeler & J.M. Silk (eds.), Mind the gap. Tracing the origins of human universals. Berlin: Springer, 331-349.

To be included:

Pascual-Garrido, A. (2019). Cultural variation between neighbouring communities of chimpanzees at Gombe, Tanzania. Scientific Reports 9(1): 8260.

Pruetz, J. D., & Lindshield, S. (2012). Plant-food and tool transfer among savanna chimpanzees at Fongoli, Senegal. Primates, 53(2), 133-145.

Whiten, A. (2020). Wild chimpanzees scaffold youngsters’ learning in a high-tech community. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(2), 802-804.

Musgrave, S., Lonsdorf, E., Morgan, D., Prestipino, M., Bernstein-Kurtycz, L., Mundry, R., & Sanz, C. (2020). Teaching varies with task complexity in wild chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(2), 969-976.

Musgrave, S., Morgan, D., Lonsdorf, E., Mundry, R., & Sanz, C. (2016). Tool transfers are a form of teaching among chimpanzees. Scientific reports, 6, 34783.

Musgrave, S., Lonsdorf, E., Morgan, D., & Sanz, C. (2020). The ontogeny of termite gathering among chimpanzees in the Goualougo Triangle, Republic of Congo. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 2020: e24125.

Valentine Roux 7 December 2020 (16:55)

flexible use of techniques

Thanks for this draft and the different issues your raise.

Among these issues, you discuss the flexible use of techniques. You write « With an increase of the variable elements of a technique, the potential variability and flexibility in use augment ». Studies in technical skills involved in stone knapping have shown that learning consists in progressively mastering the elementary gestures on an ever changing environment, namely the raw material which is never homogeneous, and that flexibility in planning, namely optimal planning abilities, is conditioned by motor control (see Bril and al’s articles).

What could be this « increase of the variable elements » in stone knapping? The properties of the raw material ? Not sure I well understood. We associate the word flexibility with expertise (see our paper and comments). What about you ?

My second question would be about the different transmission procedures? How can you study it for ancient periods, knowing that even nowadays no craft technique, whatsoever, require specific modes of transmission (no oral instructions are necessarily required ; most of the time, not even demonstrations ; just advices in the course of making if necessary)?

Mathieu Charbonneau 22 December 2020 (11:36)

"Developmental" mechanisms in flexible/rigid use and transmission

Thank you Miriam for your early draft.

I particularly like how your link the situatedness, embodiment of technique learning and transmission along the three dimensions of development you identify, and I am looking forward to see how this develops further in the later draft of the chapter. Reading you draft, I had similar questions to Valentine's, so let me emphasize on different points. My questions are very open-ended, so please answer as you see fit.

At first, it seems you are adopting a developmental approach, pushing aside an ideational approach to technical culture and instead focus on the co-construction of techniques, individuals, and their environment (e.g., you mention techniques can become embodied, you speak of material engagement and place a great deal of focus on the environment structuring the development and transmission of techniques, etc.). However, when discussing rigidity in transmission, you seem to revert back to a more cognitivist (imitation, shared attention, intentionality, etc.) approach, which is typical of an ideational approach to culture. Is this an inadvertent change in focus or do you see this as an important aspect in differentiating flexible and rigid transmission?

I would also like to know more about what role 4E cognition could take into your account (e.g., through embodied cognition and/or material engagement theory), especially how these are articulated, perhaps differently and/or in similar ways in the context of flexible/rigid technical use vs. transmission. Additionally, considering that techniques are hybrid entities, one foot in cognition, another in action, and yet another in the environment (materials, artefacts, etc.), what role do you see environmental/ecological resources playing in the transmission of flexible/rigid techniques? Do you see any key mechanisms of change in the environment that could act on all three dimensions, or differently on different dimensions?