- 'Cultural Evolution in the Digital Age' Book Club

Consuming vs. sharing information online

In his brilliant book, Alberto notes a series of significant differences between information sharing in oral cultures and online (to take two extremes). Oral cultures are dependent on memorization for information to be transmitted. By contrast, online, information can be shared with a click, without being memorized (or even, in some cases, without being read: think of those who always retweet content from such and such source). Obviously, much as is the case for offline written culture, that some information can be shared without any memory requirements doesn’t mean that all (or even most) information is shared that way: for example, people also talk offline of what they’ve read or seen online (indeed, this two-step flow process is supposed to play a key role in the propagation of information). Still, it remains the case that sharing information without much by way of memory constraints is much more common online than offline.

Memory constraints offline mean that much content that people might enjoy is unlikely to spread and persist, because too few people are able to remember it. One might then expect that the partial abolition of these memory constraints online leads to a better alignment between what content people are interested in, what content they share, and thus what content spreads.

However, it is far from clear that such is the case. Alberto discusses a study of the most emailed New York Times articles which found that the most popular articles were overwhelmingly positive—which flies in the face of the well-known and supposedly omnipresent negativity bias, by which people pay more attention to negative information. In an earlier post, Sacha Altay mentioned a study by Jonathan Bright (2016), which compared the most read and the most shared articles on the BBC News website.

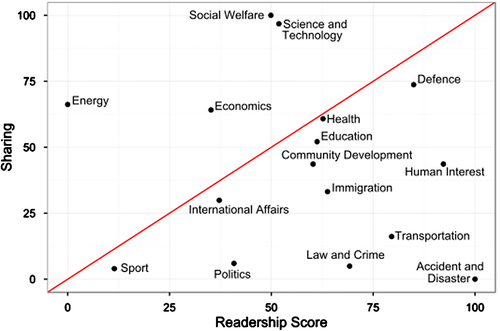

As this figure from his article reveals, there is no correlation whatsoever between what people read and what they share (the scores are normalized, such that 100 is simply the maximum score). To take a striking example, the “accident and disaster” category (which also comprises crime) was both the most read and the least shared.

As Sacha notes, many other examples come to mind immediately, such as sex (compared to other topics, people consume much more content about sex online than they share). Why would we observe such large gaps between what people consume and what they share?

As Alberto notes, the ability to share information is, oftentimes, not the most stringent constraint on what information gets shared. Instead, a lot of information isn’t shared because people are unwilling (instead of unable) to share it. The “AAAAAAAAAA” string Alberto uses as an example is easy to remember (10 As), but too dull to be transmitted in all but the most specific contexts. However, such examples don’t quite explain the consumption / sharing gap: people are interested neither in consuming nor in sharing the letter string. To take the opposite example, Pascal Boyer has shown that people are more likely to share threat-related information, but they are also more likely to want to consume such information, so that the consumption / sharing gap isn’t explained either.

Cognitively, we should expect people to rely massively on what they find relevant to approximate what others will find relevant. While there are obvious adjustments to be made to account for individual differences in interests and knowledge, this form of ‘egocentric bias’ is a sound heuristic. Again, this only highlights the puzzle of why there should be, at least sometimes, and even in the absence of memory constraints on sharing, such a strong divergence between what information we consume and what information we share.

To better understand the divergence between the information we consume and the information we share, it’s good to think a bit more about the motivations for sharing information. Very roughly, we can divide these motivations into informing others and managing our reputation (with many messages doing both). If I tell my wife I’ll be late coming back from work, my main goal is to inform her. If I tell a colleague that I had a paper published in a high-ranking journal, I’m managing my reputation.

My intuition is that social media are much better suited to serve the goal of managing reputation than of informing (although, again, a statement shared to manage reputation can also inform, and vice versa). Typically, the motivation to inform targets very specific individuals, whether it’s just one (my wife), or several thousands (e.g. the employees of a company). In either case, targeted communication seems much more suited to the task than social media.

By contrast, when seeking to enhance our reputation, we can, in many cases, afford to be much less discriminating in who our audience is. I wouldn’t tell my wife I’ll be late for work on Twitter (even if she were on Twitter), but I might happen to mention on Twitter a publication in a high-ranking journal.

Sacha pointed out some of the specific dimensions of reputation people might seek to enhance by sharing information online (such as appearing nice). Here, I’d like to suggest that the consumption / sharing gap makes it more difficult to study the role of typical cognitive factors of attraction (sex, disgust, threats, etc.), but that, on the other hand, it provides a great opportunity to understand why people share information.

There are several reasons to believe that consumption is more deeply affected by typical cognitive factors of attraction than sharing, such as:

1. To enhance our reputation as competent sources, we might be particularly keen to share novel information, such that novelty can in part make up for a lack of other qualities (such as tapping into typical cognitive factors of attraction).

2. To enhance our reputation as a good coalition member, we might share information that is, with some degree of arbitrariness, positively associated with our coalition, such that, again, this association can in part make up for a lack of other qualities.

3. The very popularity of some information, arguably driven in large part by its ability to tap into typical cognitive factors of attraction, can create an association between this information and some coalitions of society. As a result, members of other coalitions might be reluctant to share such information (potential examples include celebrity gossip, which came to be associated with lower classes, and which other classes might be more reluctant to share, on social media at least).

4. The costs of sharing the wrong information in a botched attempt at managing our reputation are likely to loom larger than the opportunity cost of failing to share information that would have improved our reputation (if only because the latter is typically invisible). This might be why many people who consume information online simply do not share any of it (every social media site has its lurkers). This means that information will only be shared by a restricted sample of the public, which (a) might happen to consistently differ from the overall public in some traits (besides being more likely to share information in general) and (b) in any case, by the sheer virtue of being a smaller sample, is more sensitive to random fluctuations.

All of this means that it will likely be more difficult to find a role for typical cognitive factors of attraction in online cultures that largely depend on sharing (as Sacha notes, this is true of some platforms, but not by any mean all).

One advantage of the consumption / sharing gap observed online is that it can make it easier to study people’s motivations for sharing information. For example, different social media sites appear to best serve different reputation management goals (e.g. Twitter might be well suited to display one’s competence, and Facebook one’s warmth). It should be possible, within each site, to study the content that creates the consumption / sharing gap (i.e. what content is likely to be consumed but not shared, or shared but not consumed), and to attempt to match that content with the presumed intentions (or to test hypotheses about which reputation management goal will be best served by sharing which content).

***

Bright, J. (2016). The social news gap: How news reading and news sharing diverge. Journal of communication, 66(3), 343-365.