The space of reasons and the generation of knowledge

In 1644, in disturbing times of civil war and religious fanaticism, the English poet John Milton held a passionate plea for the freedom of the press. He wrote: “Where there is much desire to learn, there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions; for opinion in good men is but knowledge in the making.” With these words, Milton touches upon an idea that other thinkers too have recognized, namely, that if you let people argue freely, each from one’s own perspective, they will tend to come up with pretty good solutions.

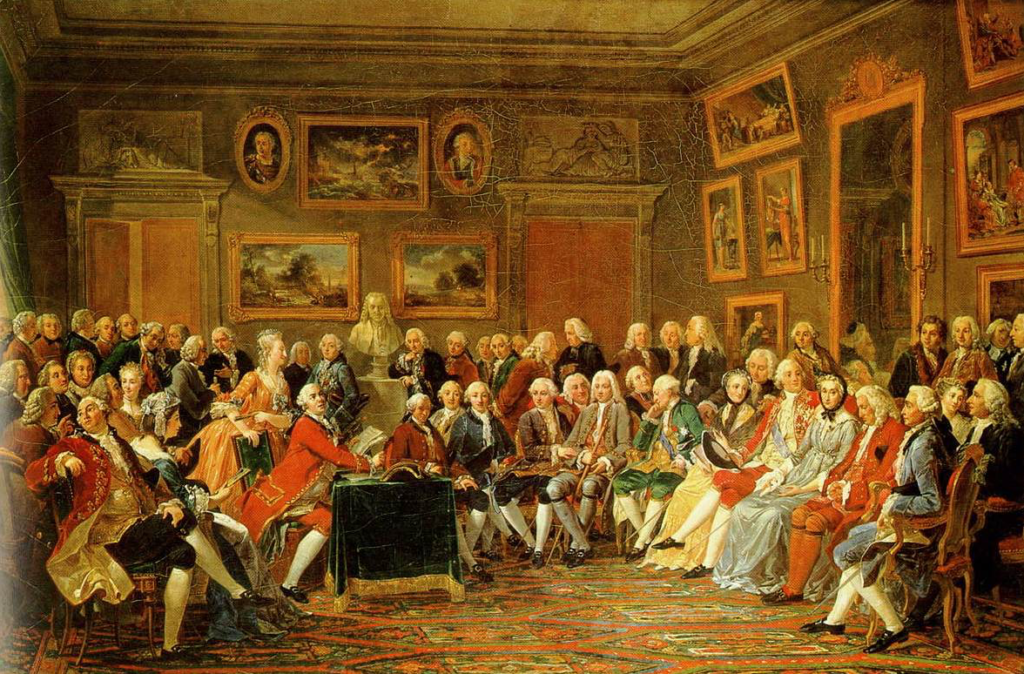

Reading of Voltaire's L'Orphelin de la Chine, in the salon of Madame Geoffrin by Lemonnier (1812).

Reading of Voltaire's L'Orphelin de la Chine, in the salon of Madame Geoffrin by Lemonnier (1812).

Socrates and Plato, for instance, intuited that reasoning in the form of a dialogue leads to some form of knowledge. Jürgen Habermas speaks of “communicative rationality”. But why is this exchange of reasons so important? Doesn’t reasoning in private deliver us “clear and distinct ideas” as the French philosopher René Descartes once thought? Or is reasoning then not a process by which individuals correct their intuitive and emotional thinking as recent psychological research suggests?

The interactionist theory of reasoning, recently developed by cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber in their wonderfully inspiring book The Enigma of Reason, proposes that the evolutionary function of reasoning is not to improve our own behaviour and knowledge. Instead, we should understand the origin of reasoning within a social context. We provide reasons to convince others or to justify ourselves. As the authors put it: “Reasons are for social consumption”. This implies that, from an evolutionary perspective, our reasons do not necessarily have to be good, but only efficient. They need to serve our own cause, and if that works well with simple arguments, then why bother looking for better, but more complex ones? Our reasoning therefore is biased and lazy. If that’s the case, however, how does reasoning result in knowledge? Are sophists, rhetoricians, and lawyers right in claiming that reasoning is not about being right, but merely about persuading others?

Indeed, it seems we would have to agree with these masters of the word. However, there is another factor at play, namely the people to whom the reasons are addressed. We are not too easily swayed by other people’s arguments, because that would leave us vulnerable to deception and manipulation. If a pharmacist tries to sell us a homeopathic potion saying that it helped her and her family, we are reasonably sceptical because anecdotes don’t count as scientific evidence. Similarly, we do not simply accept justifications. If a friend claims that he stole an Iphone just for the thrill we will tell him right and perhaps even avoid him in the future. The norm that the reason implies is unacceptable. Our stealing friend then has the option to provide better reasons – if there are any available – or to adjust his behaviour, at least if he wants to be tolerated again by others. In sum, when evaluating reasons we tend to be much more critical than when we produce them. And this creates opportunities.

Humans are, as far as we can tell, the only species on this planet that reason (in the strict sense of producing and evaluating reasons). As such, we have entered what the American philosopher Wilfrid Sellars labelled the space of reasons. We cannot simply say or do things; others can always ask for an explanation: Why do you believe this, why do you think you know this, why do you behave in such and such a way? At first, our reasons will not be very good, as long as we can get away with them. The critical eye of others, however, obliges us to search for better reasons. When we can no longer provide such reasons, we are forced to change our beliefs or adjust our behaviour. There are no reasons left in support of the existence of God, witches, and unicorns; the excuses for slavery or female circumcision are exhausted. Instead, we now have relativity theory and the universal declaration of human rights. Our interactions in the space of reasons result in better knowledge, behaviour, and societies.

But is knowledge no more than a consensus about reasons then? Does this mean that the most skilled rhetoricians will determine what counts as knowledge? Isn’t the truth relative to whatever group has managed to rally the most support for its position or cause? Not quite. Philosophers and social scientists who defend such claims overlook the fact that convincing arguments tend to be good arguments. Once we have more or less agreed upon what are the best available reasons, the position that these reasons support is true (or the most desirable option). As the pragmatist philosopher Charles Peirce put it: “The opinion which is fated to be ultimately agreed to by all who investigate is what we mean by truth and the object represented in this opinion is the real.”

The space of reasons can only have this effect when people are allowed to formulate and evaluate reasons. If not, we end up with dogmatism and totalitarian regimes. Science and democracy par excellence constitute spaces in which reasons can freely circulate, resulting in the most wonderful outcomes: Extraordinary knowledge about all relevant aspects of the world, including ourselves, and societies that enable people to flourish. Only these “open societies”, as Karl Popper called them, provide the conditions in which, in the form of constant dialogue, opinion turns into knowledge.

Gloria Origgi 19 December 2018 (12:22)

"Second order" reasons

"The space of reasons can only have this effect when people are allowed to formulate and evaluate reasons. If not, we end up with dogmatism and totalitarian regimes. Science and democracy par excellence constitute spaces in which reasons can freely circulate, resulting in the most wonderful outcomes: Extraordinary knowledge about all relevant aspects of the world, including ourselves, and societies that enable people to flourish."

Not sure which kind of "reasons" people should be allowed to formulate when they have to evaluate a new scientific result. It seems much more rational in many cases to be able to articulate "second order" reasons such as: who says that? who funded this research program? who decides about the benefits of this scientific innovation for humanity? Abstract reasons outside the realm of politics of science don't seem to me to be enough anymore to generate a "space of reasons" that make us autonomous thinkers.

Stefaan Blancke 21 December 2018 (17:40)

Reasons, inside and outside of science

Thank you for the comment, Gloria, and my apologies for the belated response. It would indeed be interesting to see what reasons are thought relevant and thus become more available within different contexts. The study of (the causal factors underlying) the distribution of reasons would be part of an epidemiology of reasons, which I hope to develop further in the future, especially in relation to science, science education, and the public understanding of science. But I fully agree that one can expect that people’s access to reasons will depend on their ecology, their background beliefs (e.g., level of education), their motivation, and so on. As such, the reasons available inside and outside science will be different as well. Non-scientists might have to take more recourse to second-order reasons, but such reasons also play a large role in science where trust is important (particularly in interdisciplinary work). Furthermore, even when one has to rely on second-order reasons, one can still try to make a distinction between good and bad reasons (e.g., for an exploration of good reasons one can have for trusting an expert, see Alvin Goldman’s “Experts: which ones should you trust” (2001)). So the space of reasons might generate reliable knowledge about who to trust.