Why are Romanian cars and real estate priced in euros? A particular case of Thiers’ Law

In contemporary Romania, the prices of real estate (sale or rent) and cars are expressed in euros, even though most transactions involve lei (singular leu, the national currency). Sometimes wages and contracts are also settled in euros, and people often think of how much they are earning in euros despite the fact that actual payments are in the national currency. Why is that?

One explanation is currency substitution. A domestic currency which suffers from high and unpredictable inflation becomes displaced by a stabler, foreign currency available in the market. Given its historical stability, availability and supply, US dollars have played this role, either officially and unofficially.

This is an example of Thiers’ Law, the opposite to the more famous Gresham’s Law which. states that, given fixed exchange rates among two kinds of money, bad money will drive out good money. Peter Bernholz gives an example from ancient Greece:

Athens had to maintain great military expenditures at a time when its hinterland including the silver mines of Laurion had been occupied by Sparta. Thus its governments turned to issue silver coated copper coins of the same nominal value as the full-valued silver coins issued earlier, which implied a fixed exchange rate between the two kinds of money. But only the old coins could be used for payments abroad and were also preferred by the population because of their much higher intrinsic value. Consequently they vanished abroad or were kept back in hoards. The bad money drove the good one out of circulation. [1]

Thiers' Law states that with flexible exchange rates and sufficiently significant differences in the rates of inflation of two currencies good money will drive out the bad one. When people do not trust in the “bad” (i.e. erratic and constantly devaluing) domestic currency, they not only hoard but also start transacting in the “good” (i.e. predictable and stable) foreign currency. The phenomenon appeared in ancient China, the Roman Empire or Weimar Germany where hyperinflation led to the value of economic transactions in foreign currency being ten times as large as that of circulating paper mark notes in 1923. [2]

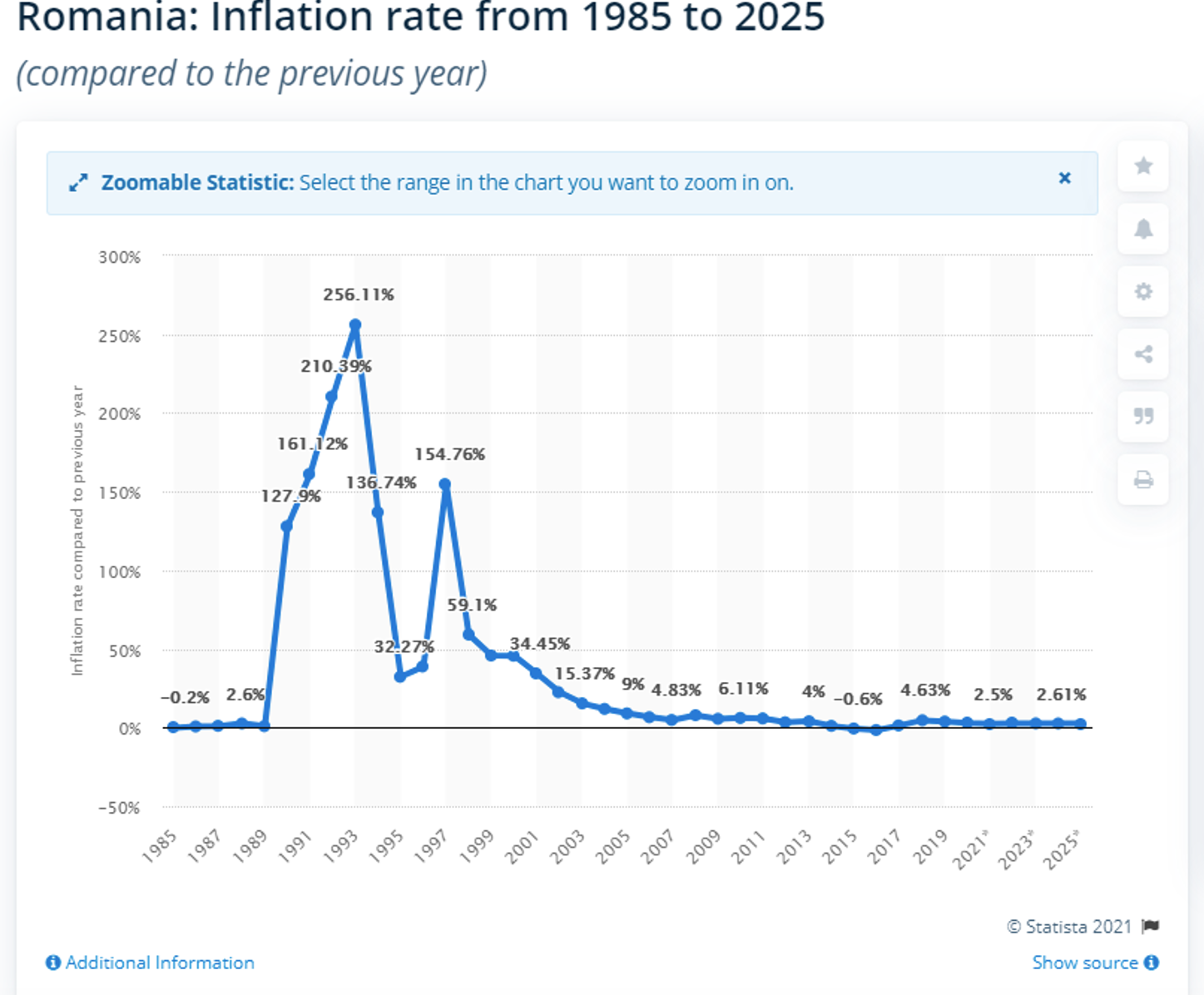

People hoarded US dollars and even more Deutsche Marks before 1989, when the official exchange rate was fixed at about 3 times lower than the black market rate. The state prohibited people from having foreign currency and forced them to sell it at the miserable official rate. At the same time, some goods like foreign cigarettes, alcohol and other desirable things were sold by state shops (known by everyone by the English word “shops”) only for foreign currency, so citizens tried to get their hands at the coveted US dollars and German marks. Furthermore, Romania did suffer from high inflation after the fall of socialism, reaching over 250% in 1993. From 1990 to mid 2000s, pricing high value goods in foreign currency made economic sense because it insured from uncertainty. This painful history may still be remembered by some citizens who would rather not risk selling their goods in a currency which could devalue overnight. Especially in the case of rents or wages, signing a contract (or shaking on an informal deal) in euros provides some insurance against sudden fluctuations in exchange rates. Hoarding foreign currency such as US dollars, Swiss francs or euros would also make sense as a safer store of value than lei.

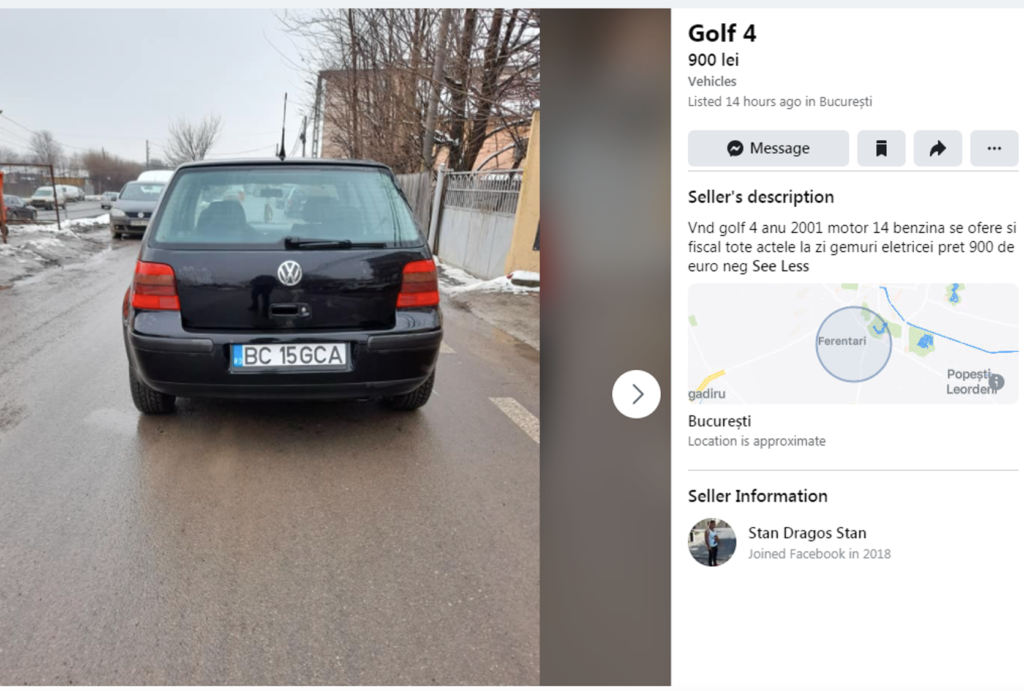

The stickiness of euro-pricing makes a fascinating appearance on Facebook’s Marketplace which has lei as default pricing currency. I was looking for a car and I noticed that the prices were ridiculously low. 900 lei for a VW Golf??? But then I read the description which said that the price was in euros, irrespective of the lei price shown on Facebook. There is no incentive to communicate the price in lei on Facebook because then one would compete in attention and search engine algorithms with other offers with apparently 5 times lower prices.

To give this a Gricean twist, what is written (said?) on the Facebook ad is 900 lei; what is meant is 900 euros.

There are no costs for communicating a literally false information - no-one could believe that a functional 2001 VW Golf 4 sells for less than 200 euros, and even if such a naive or hopeful customer would inquire, the seller could easily communicate the real price (and perhaps explain why he “lied” in the ad due to FB inducing a lei pricing on a market which is dominated by euro pricing). The pricing in euros is thus common knowledge, but even when it is not, the real price can be easily communicated.

The stickiness of euro pricing also appears with providers of services such as telecommunication (internet, TV, mobile phone networks) who price their subscriptions in euro even though invoices and payments are in lei. The likely explanation is similar to what happened in real estate and car markets. The large providers started their business in the late 1990s, when lei inflation was still high. The need for predictability in contracts made them prefer euro pricing at first, and then they had no reason to change to lei

Rents present a fascinating case of mixed pricing. Many rents are expressed in euros (and sometimes the landlord demands actual euros - as mine does). This is advantageous to the owners since the leu devaluates slightly compared to the euro in the long term (inter alia, the inflation rate for lei is higher than the inflation rate for euro). But many times, the rent is expressed only in lei. The shift is, most likely, driven by the needs of tenants. Since most wages are expressed and paid in lei, tenants want a predictable rent which can be computed as a share of their income. Since exchange rates can change more rapidly than salaries, the tenant would risk more than landlords and they also have bargaining power to impose a deal priced in lei.

In contrast, the buyer of an apartment does not care if the price is in euros even when they pay with lei. Even better, when they use a mortgage expressed in lei they benefit from the devaluation of lei compared to euros (but of course banks take this into consideration when computing their interest rate, especially when these are not fixed but pegged to ROBOR - the Romanian Interbank Offer Rate).

Therefore, until sellers and/or buyers have an incentive to shift pricing to lei or the state (or other powerful institutions) force them to do so, euro pricing is culturally attractive for Romanian high value goods.

Some questions remain outstanding. Perhaps it is just easier to mentally process smaller than larger numerals. Maybe our minds find it easier to use 950 rather than 4500 when evaluating values. Why would that be the case?

Also, what is the role of Romania’s intense relationships with other EU economies? While Romania is not part of the Eurozone, most commercial foreign transactions are made with EU actors and priced in euros. On top of that, an immense Romanian diaspora works in the EU and sends back to Romania remittances in euros (and pounds, in the past few years). What happens in other countries with a different place in the geo-eco-political map? I am thinking of countries such as Moldova (equally influenced and linked to the EU and Russia), Georgia, Armenia or Uzbekistan (relatively more influenced by Russia)?

In any case, when Romania will join the Eurozone, one part of its economy will need no adjustment. Cars and houses will be priced in euros just like before, but this time the money changing hands will be actual euros.

[1] Bernholz, P. (2011). Understanding Early Monetary Developments by Applying Economic Laws: The Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments, Gresham's and Thiers' Laws. Gresham's and Thiers' Laws (March 31, 2011).

[2] Bernholz, P. (1989). Currency competition, inflation, Gresham's law and exchange rate. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE)/Zeitschrift für die gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 465-488.