Why do we make our tastes public?

Facebook has recently changed the way it asks its users to endorse brands and celebrities on the site. Rather than ask people to "become a fan" of say, Starbucks or Lady Gaga, Facebook will instead let users click to indicate that they "like" the item.

Facebook already lets people "like" comments or pictures posted on the site, and users click "like" almost twice as much as they click "become a fan." Facebook says that replacing "become a fan" with "like" will make users more comfortable with linking up with a brand and will streamline the site. The Independent quotes Michael Lazerow, CEO of Buddy Media, which helps companies establish their brands and advertise on social networks such as Facebook: "The idea of liking a brand is a much more natural action than [becoming a fan] of a brand. In many ways it's a lower threshold."

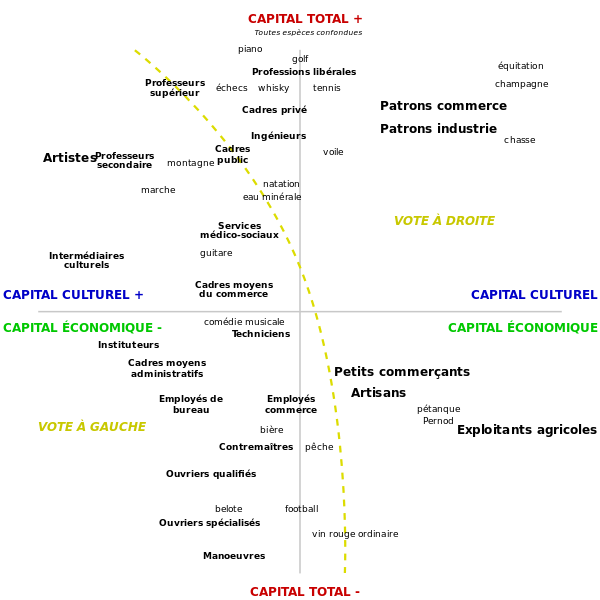

But while it might seem to be less of a commitment to declare that you "like" Starbucks than to announce you are a fan of it, the meaning essentially would stay the same: Your Facebook friends would see that you clicked that you "like" a page and that’s why users do it anyhow: to advertise their good taste or, to use Bourdieu’s famous term, their “distinction” (below the break is one of the famous Bourdieusian graphs where cultural and economic capital are related to cultural practices. Although the data are quite old now, it still is fun to plot oneself in this kind of space).

While reading The Independent, it came to me that the case of Facebook was relevant to a previous discussion on the ICCI blog: Why do ad-men think that people will buy more razors if they are advertised by Beckham?

A bunch of explanations was proposed to explain such a phenomenon. The first one was Robert Boyd's from whom Olivier Morin borrowed the example of Beckham. Boyd likes to illustrate prestige-biased imitation with the picture of David Beckham lending his name and face to sell razorblades. Olivier commented that this explanation suffers from several problems (is it really based on prestige? are we so dumb?). And following Olivier’s post, several alternatives were proposed such as coordination (by Jean-Baptiste André), sympathy toward Beckham (by an anonymous guest), attention grabbing (by Christophe Heintz).

Facebook’s “I like it” may offer another explanation, namely that people buy many goods to advertise their good taste and display their values. Take coffee for instance. By choosing a particular brand, you can convey information about your tastes, your degree of trendiness (think Nespresso), your wealth (think the price of a coffee at Starbucks), your political opinions (think fair trade, organic coffee, support of local communities), etc. (And, indeed, as I noted in a previous post, the more inegalitarian the society, the more people compete with each other and the more brands invest in advertisement).

Similarly, you do not convey the same signal if you wear a Beckham T-shirt or, say, a Cantona T-shirt (I guess I should update my knowledge of the Premiere League...). These two players are quite different and do not evoke the same values.

In a way, Facebook can be seen as a handy device to send a lot of very precise signals about your opinion and your values! (The average user becomes a fan of four pages every month, according to Facebook). Note that this theory of marketing is just a form of honest signal theory, advocated previously by Veblen in social sciences and Zahavi in evolutionary biology. The difference is that, instead of being focused on the display of wealth, this bourdieusian explanation is interested by other qualities that also need to be adverstised by individuals such as intelligence, social connections, moral disposition, etc.

To conclude, people may buy razors advertised by Beckham not because they think that these razors made Beckham successful or because they trust Beckham is such matters but because buying a razor linked to Beckham convey a certain message about their distinction (below the poster of "Le bonheur est dans le pré", a film with Eric Cantona, defending a certain epicurian French way of life, full of friends, simplicity, culture and foie gras, quite far away from the tacky touch of the Beckhams).

Paulo Sousa 25 May 2010 (02:11)

Hey Nicolas, You said: Facebook’s “I like it” may offer another explanation, namely that people buy many goods to advertise their good taste and display their values. Do you see this explanation as an alternative to a prestige-based imitation type of explanation? If so, why exactly? Paulo

Nicolas Baumard 25 May 2010 (13:08)

Hi Paulo, Yes, I see this explanation based on signalling (or distinction) as an alternative to the theory of prestige (although not incompatible). The theory of prestige advocated by Boyd and Henrich (and used in the recent article on chimpanzees recent article on chimpanzees states that individuals imitate successful individuals in order to use their recipe of success (I see that Beckham has been successful by playing football so I decide to be myself a football player). So successful people are influent because others ahve an interest in imitating their behaviour. The theory of signalling I propose states that successful people are influent partly because they are used as a way to advertise one's tastes. For instance, I wear Lady Gaga's outfits (this cannot be a real example...) in order to show how trendy/sophisticated/freack/open-minded/decadent I am. In this theory, I don't have to really imitate Lady Gaga or Beckham (and thus if Beckhma does use the razor he advertises, it don't really care). I just have to find a behaviour that convey the idea that I like Gaga (and therefore I am trendy/sophisticated/freack/open-minded/decadent). Note, of course, that both theories are not mutually incompatible.

Rita Wing 25 May 2010 (17:26)

"........defending a certain epicurian French way of life, full of friends, simplicity, culture and foie gras, quite far away from the tacky touch of the Beckhams)......." If the alternative to a life where one accepts the appalling cruelty of foie gras production (explicitly forbiddden for its inhumaneness in many European countries - not that their own standards are much to write home about)is a bit of tackiness, bienvenido sea, I'll sign up for tackiness over cruelty any day! "Le Bonheur est dans le pré" indeed - only if your own momentary bonheur is the only thing that matters to you.

Nicolas Baumard 25 May 2010 (17:45)

Dear Rita, I quite agree with you that foie gras is a cruel. However, I don't think that the alternative is between being a french epicurian who eats foie gras and a tacky businessman who does not eat foie gras for you can be a very happy epicurian without eating foie gras. Plus you should not embrace tackiness to quickly. Think about the carbon footprint of the Beckham's (luxury goods, huge villas, jet society) and you will see that such way of life may make much more people and animals suffering.

Paulo Sousa 25 May 2010 (18:46)

Thanks for the reply, Nicholas. It seems that cases of display of endorsement do not necessarily involve imitation and that cases of imitation do not necessarily involve display of the characteristic being imitated, but in cases of imitation that also involve display of the property imitated, wouldn't that be always and simply an instance of prestige-based imitation with display? For example, if I admire some prestigious person, imitate some of his/her characteristics that I think is associate with the person being prestigious, and display that I have that characteristic, wouldn't I be trying to acquire the same social success coming from the prestigious person having that characteristic?

Emilio Blanco 25 May 2010 (19:52)

I like your post!

Nicolas Baumard 26 May 2010 (11:38)

...but a true theory? Yes, prestige-based imitation may be more simple. But as Olivier observed in his post on Beckham, prestige-based imitation may not be very important: "In order for the theory to work, (...) prestige-based imitation must obey two criteria: first, it has to be independent of the actual content of the behavior that is copied (in the words of the theory, it has to be context-dependent, not content-dependent). In other words, when you imitate David Beckham by buying razorblades, your decision has to be based on David Beckham's charisma alone, and not on some inference you made about what the razorblades do. Suppose, for instance, that you chose to buy the razorblades because you believe they are responsible for Beckham's subtle, artful, faux négligé three-days beard - after all, TV lore teaches that there is a direct causal link between a good razorblade and a great sex life (I see our friend the ad mogul nodding). Then your decision is based on information that ultimately has to do with razorblades - and sex - but not with Beckham. The advertisement team has wasted money paying him: a nobody with a great 3-days beard woul have done the deal. You might also have bought Beckham's razorblades because you were under the impression that they contributed significantly to his winning the heart of a former Spice Girl - which many people consider a success in life, at least in the UK. In that case, the advertisers lost their money on Beckham all the same: any other former-Spice-Girl's husband would have done the deal, at a cheaper price. In both these cases, your decision did not originate in your admiration for Beckham, but in the perceived effects of buying a razorblades, as evidenced by the case of David Beckham. You were influenced either by David Beckham's supposed skills in choosing rasors, or by David Beckham's success. (...) What happens if we don't push all these instances of imitation not based on prestige under the rug? This: if your decision to buy the same razors as Beckham was not based on Beckham himself, but rather on his good looks, or on his decent (by Girls-Band standards) romantic life, then you have no reason whatsoever to imitate him when he decides to become a suicide bomber or a Buddhist Monk. And advertisers lost their money." Olivier concluded: "I have no proper conclusion to offer, only a challenge: I am not aware of any good study unambiguously showing a case where imitation is clearly detrimental to the imitator, and clearly motivated by the model's prestige alone (that is, excluding his perceived skills or his success, real, expected or assumed)."

Jean-Baptiste André 27 May 2010 (14:01)

Great post and great theory! Yet, I would like to defend a little bit my own (coordination), because it is in fact very close to yours! Coordination is a more general issue than what we usually think. Otherwise there would obviously be no coordination problem in choosing a razorblade. Coordination problems arise as soon as one needs to know what others are likely to find cool, trendy, exciting, desirable etc. One needs to “coordinate” with others’ tastes. Not necessarily for operational reasons (what we usually think of when we think of coordination, like driving on the good side of the road, etc.) but also and far more generally for reputationnal reasons. And, in this “coordinating” role, public information such as commercials play a key role (e.g. through the link they establish between brand names and famous people, etc.). Isn’t what you suggest related to this idea ? (Even though, I agree that presenting this as a coordination problem is not the most natural way to do)

Nicolas Baumard 28 May 2010 (18:27)

I agree in theory, it could be advantgeous to display one's ability to coordinate with others. However, it seems to me that the usual examples of imitation in clothes or technology are not about displaying one's ability to coordinate but rather one's ability to be on the edge of society.

Andrew Hirst 29 May 2010 (14:15)

I just have a quick question: I fail to see how "liking" products on Facebook is an example of honest signalling. It seems that it would be quite simple to "like" anything you want with relative ease without having to invest any serious effort into it. There is no real cost involved in this, unlike conspicuous consumption and handicaps in evolutionary biology. These are "honest" signals because of their extreme costs. "Liking" on Facebook is very cheap and could easily be dishonest.

Dan Sperber 30 May 2010 (02:46)

I agree with Andrew Hirst, signalling something about oneself by means of Facebook 'likes' is not a case of honest hard-to-fake (let alone costly) signalling. Nicolas suggested that "in away" it was. In what way?

Nicolas Baumard 31 May 2010 (14:19)

As I noted in my post, honest signalling is often seen in term of costly signal (which, and among humans, essentially means expansive signal). However, the important point is not the cost of the signal but the difficulty to fake it. Think for instance to the new richs. They often try to look sophisticated by buying old mansions, collecting contemporary art or going out in sophisticated restaurant. But most of the time, as Bourdieu noticed it - as many others before him, in particular the old richs who look down to these tacky self made men - new richs do not have enough cultural capital (that is education, implicit skills, etc.) to really look sophisticated. In other words, they want to send the signal that they have lots of cultural capital, but they fail to do because cultural capital is hard to fake. What Facebook does si to makes tastes cheap to display. But it does not change the game described by Bourdieu. Indeed, you still need skills and education to pick up the right signal. It is very easy to say that you like Paulo Coehlo or Michel Houellebceq, but it requires some cultural capital and some aesthetic sensitivity to know that the later is artistically more ambitious. Thus, the signal ('I like Houellebecq') is hard to fake although it is cheap to display.