Friends

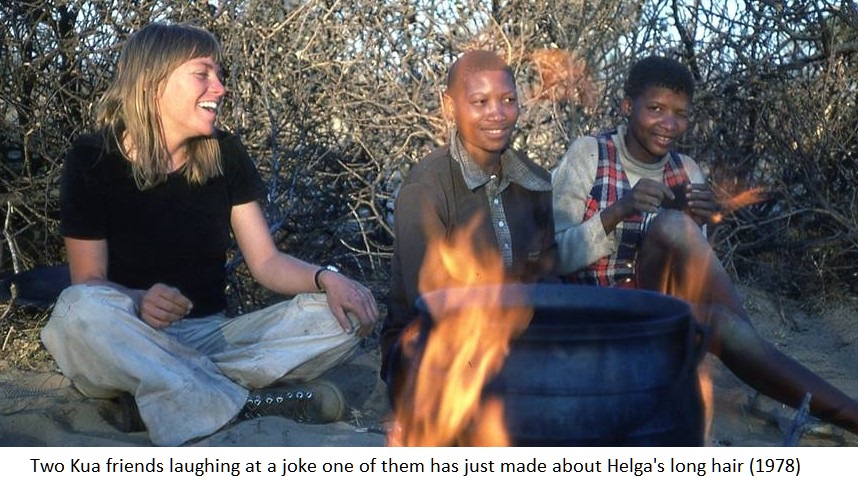

We asked Helga Vierich to share with us as a guest blogger anthropological reflections on friendship and social networks based on her fieldwork among the Kua hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari. Helga has a PhD in anthropology from the University of Toronto, and teaches at the Yellowhead Tribal College in Alberta.

Friendship is kinship by another mother.

Why is this so important among humans?

Well, consider what I found when studying the lives of hunter-gatherers in the Kalahari. I found that all the people were living in multi-family groups - camping parties - consisting of friends - as well as of kinfolk. Camping parties among the Kua were typical of the kinds of “groups” encountered when you go visit mobile hunter-gatherers.

Early researchers called them “bands”. Networks of mutual support, often symbolized by exchange of gifts, and other efforts to keep in touch, form the essential social networks that constitute the basis for individual reputation, and such reputations often literally anticipate any social contact. Even when the neighbors speak mutually unintelligible languages, as among the Kua and their neighbors the G/wi, and G//ana, it hardly mattered; many people were multilingual.

Among the Kua adults, belonging to a wider circle of valued companions, consisting of both relatives and friends, is of paramount importance. This is highly significant in terms of mate selection and reproductive success. The greater the number of network connections that were drawn together around a particular person, the greater the "relationship wealth" of that person. This was the most significant quality assessed, for example, in a prospective mate.

The size and influence, of any one individual’s position, as a hub, in a cloud of acquaintance where many networks connected, appears to reflect personal reputation. This is not necessarily determined by material wealth, but rather by evidence of trust-worthiness, generosity, and other signs of character, and these are still highly valued in almost all human communities.

Among most hunter-gatherers, it is from such a small pool of “hubs” (trusted and respected persons) that households coalesce into camping parties. At larger aggregations, people thus connected by kinship and friendship may also assemble spontaneously into temporary task forces, often under the direction of the high-ranking elders. These work to clear brush from campsites, gather building materials, set controlled fires, and police minor conflicts. Childhood friendships loomed very large among these hunter-gatherers. Attachments to other children seemed to become more and more important to each child as they grew older. These were attachments to unrelated children in about equal proportions to blood relatives — just as it is among people in bigger cities today, your best friends were not necessarily your siblings or even first cousins. Among the Kua too, close friends were as likely to be children of people your parents do not know well as they are to be the children of your mother’s oldest friend . Even among the Kua I found that some people had lifelong friends who had been born in another language group altogether. I recall being told by a young girl that she always longed to see a best friend who was the daughter of a G/wi woman, one of two daughters she brought with her, after their father died and the widow then remarried a Kua man. This was to clear up my initial confusion, because the new stepfather was the uncle of the girl, so I kept calling this friend of hers by the term for “cousin” until I learned the full history.

Friendships among these hunter-gatherer children were often fraught with sad absences. Because camp membership was fluid, close friends might find themselves parted when their families lived for a time in different camps — whether these were five or a hundred miles apart. So children’s friendships kept getting interrupted and renewed over time, as families moved from campsite to campsite. As s group trekked to the next campsite children would be eagerly anticipating seeing again those friends they had missed “because our places were too far”.

It was especially hard for children to be parted from friends they had made during the times in the yearly round when camps from different language groups shared a water point. For as much as a few months, much larger groups of children formed play groups, and Kua children interacted with G/wi, and “Tsassi” and H!ua speaking youngsters, perfecting multi-lingualism, and hearing and translating all sorts of new stories, jokes, games, and dances. Older children in their teens would set off to travel together overnight (segregated by sex), just to spend time with companions in other camps. They visited unrelated friends as frequently as cousins. There would be mixed language play-groups around the larger camps. “This is how we learn we are all one people, we are all BaSarwa,” one man told me. (BaSarwa is the common term in SeTswana language, meaning “Bushmen”.) It seems thus that a kind of larger culture-group or “ethnic” identity was forged in these childhood playgroups.

To me all of this was achingly familiar – it was like the friendships I had experienced at school, in the various neighborhoods my family lived in. Changing neighborhoods and changing schools sometimes took me too far from my friends to keep frequent contact, and I have lost touch over the years with many friends I had in school and college. I have made new ones, as most of us do, but have reconnected with older ones through social media. Humans tend, in general to maintain large individual networks, of both family and friends, and this seems to be true of every culture I have experienced. Humans, besides maintaining long-term individual networks, can also join participatory groups very fast - we evolved to join together into groups quite readily, even very temporary or impermanent groups like chess clubs, study groups, tourist crowds, and selection committees…not just hunter-gatherer camping parties. None of these groups are necessarily any kind of "in-group" that defined itself in terms of competition or opposition to an "out-group". So the idea of our evolutionary past being somehow dominated by in-group vs. out-group hostilities just will not wash.

Networks are, of course, not a human invention. Social networks are also typical of most social species. Among mammals in general, they appear to be associated with larger brains. Amiyaal Ilany, and Erol Akçay, at Penn's Department of Biology in the School of Arts & Sciences, have developed the distribution of what's known as the “clustering coefficient”, which measures such networks in a variety of social species. A great many studies in the last 10 years highlight the implications of social networks for longevity, disease transmission, or reproductive success.

Individual networking, intergroup cordiality, and fluid membership, do not just facilitate information and gene flow, of course. I was struck by the following example. There was a possibly gay couple among the Kua. They were older men, both decent hunters, and much sought after to join various camping parties since they increased the meat supply without increasing the number of dependents.

If you look at meat as a common good, shared by the whole camp, then, the more men in a camping party, the lower the dependency ratio. This means that each other man did not have to work so hard. At first I thought it was their skilled story-telling that explained why grandfathers were generally like treated like gold. On reflection, I did the calculations of how much meat they supplied, since they were generally experienced hunters.

Clearly, in hunter-gatherer camps the addition of an older couple often made the difference between the whole camping party being viable (in the sense that people did not perceive themselves to be overworked and hungry) or not.

In the times of year when the camps were clustered closer together around the remaining boreholes, Kua camps actually got smaller and smaller since the hunting success went down in these locations due to local overhunting by the Bantu-speaking farmers. Anything a man got from a snare or trap-line was pretty small (hares and guinea fowl were often taken) – too small to share with a larger camp group.

Thus at this time of year, it was rare to find more than two families per camp. People got more and more irritable as the time they had to spend out gathering food and firewood increased, and conflicts and general tension increased. People expressed longings to get back out in the bush. Even before any sign of rain, people would start leaving. They began by making camps as far from the borehole that was still compatible with daily trips to collect water there.

The problem of risk is solved with mobility and fluidity of group composition and size. Thus, dependent-heavy camping parties could be avoided. By splitting the workload among up among several camping parties containing adults of mixed age and sex, men and women could still visit their sibling’s camps frequently, but without the obligation to feed anyone there. The older cousins could go for sleepovers. Distances between camps in most clusters did not usually exceed half a day’s walk, and was often less than 30 minutes.

Freeing older people from obligatory co-residence with either male or female offspring, and adding friends to the mix, results in further flexibility. Thus, the needful constant reshuffling of personnel, experienced as sociable visiting among hundreds of people interconnected by individual networking over thousands of square miles, contributed to the health and survival of children as each household waxed and waned in size over the years. In many environments, this free movement of people among camping parties can be seen as redistribution of a productive older labor force. They could help when most needed, not according to arbitrary obligation to close kin, and not even limited to membership in kinship groups. That older couple, who had been friends of your friends for so many years that they were called by “fictive” kinship terms, were a welcome addition to your camping party.

The Kua, therefore, needed their friends as well as their families. As do we all.

That concludes the lesson. :)

And I would recommend for further exploration of this theme, a book by John Terrell: A Talent for Friendship. For further discussion of hunter-gatherer childhood, see Mel Konner’s book The Evolution of Childhood, and my essay “Culture, Play, and Parenting.”

Radu Umbres 22 January 2018 (09:10)

"Friendship is kinship by another mother."

Thank you Helga for this great account and especially the close ethnographic detail!

I would like to push the matter further into the matter expressed in the motto : what could be this common mother of friendship and kinship? I read you as suggesting cooperation, so here are questions which also drive my anthropological interests.

What happens when friendship and kinship colide? In a conflict between a friend and a close relative, which one would a Kua hunter-gatherer prefer and side with? Are people retreating towards kinship in insecure and difficult times? Or are friends an insurance against such moments?

Second, as remarked by Pitt Rivers and evoked by your data, friendship loves masquareding as kinship. But it is difficult to find the opposite case. My question would be: is there a gravitational pull towards kinship for hunter-gatheres in terms of cultural representations of cooperation, and, if yes, why?

Dan Sperber 28 January 2018 (19:39)

Friendship, alliance, coalition

Thank you Helga for this post, a great read in itself and a welcome antidote to the simplistic idea that social affiliations boil down to a us versus them mentality and an in-group vs out-group view of society. Your ethnography may also provide evidence for or against various views of friendship (for instance Peter DeScioli & Robert Kurzban's "The Alliance Hypothesis for Human Friendship"), and of coalitional psychology (for instance Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. (2010). "Groups in mind: Coalitional psychology and the roots of war and morality./a>"). What do you think?

Pascal Boyer 28 January 2018 (21:09)

Is friendship an extended form of kinship?

Thanks, Helga Vierich, for this account of Kua friendships, which raises an interesting question:

In cognitive terms, do we build and maintain friendship by using mental mechanisms geared to kinship relations? Or, on the contrary, is there some other evolved mechanism, specialized in sustaining friendship?

The “friendship as pseudo-kinship” interpretation of course takes much of its apparent strength from the fact that friendly ties are almost universally described as analogous to brother- or sisterhood. But that is a conventional metaphor. It does not necessarily reflect the actual cognitive processes involved.

Friendship is found in almost every human group, and with many recurrent features:

Friendship starts low, so to speak. People exchange small favors, then move on to larger-scale generosity;

Friendships tend to go from reciprocation to unconditional exchange. Quasi-tit-for-tat exchange may be present at the beginning, but soon gives way to pure generosity.

People have great affective investment in friendships, and are seriously upset by betrayal.

People only have a few “slots” for friends, typically up to a dozen. The others are acquaintances, with serious limits on what one can expect from them.

A while ago, Leda Cosmides and John Tooby (http://www.cep.ucsb.edu/papers/friendship.pdf) proposed to explain these features as a way of avoiding the “Bankers Paradox” – it is when you need help the most that you are least capable of reciprocating. In their account, when Alice is Bob’s friend, she extends a promise of unconditional help to Bob – and specifically to him (if she’s generous to everybody she is not Bob’s friend). But now Bob has a stake in Alice’s welfare, because it would be a pity to lose someone who is motivated to help him. So he has a reason to unconditionally help Alice. The same reasoning of course works in the opposite direction. Bob has now made himself precious enough to Alice that she will be motivated to preserve him.

Whether or not that is a valid model, the explanation points to the crucial and obvious difference between kinship and friendships. Kin are strongly motivated to be altruistic to each other because of their genetic relatedness. That is why you can be awful with your parents, as most teen-agers are (within limits, to be sure) and still expect their help.

So perhaps using kinship metaphors may help “prime the pump” of friendship by pretending that there already is between two unrelated individuals a commonality of interests, which in fact will only emerge with the passage of time. It would be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Or perhaps friendship-as-kinship is a compelling metaphor and a great cultural attractor because we have no clear explicit, reflective understanding of the recursive nature of friendly commitment.

Helga Vierich-Drever 29 January 2018 (17:43)

What happens when friendship and kinship collide? asks Radu Umbres

Well, what do you feel when it happens to you? This happens frequently during the teenage years, doesn’t it? When you have a friend your parents disapprove of? It is no different among the Kua. It really becomes an issue if it is more than friendship - but rather a sexual and emotional bond developing between two people and their relatives are discomforted.

Think of the fierce loyalty that binds “best friends” and young lovers. They will move heaven and earth to be together. Meanwhile, even your own siblings can alienate you totally, as can parents and other close relatives. It is no different among the Kua.

Among different language groups living scattered over many thousands of square kilometers, as in the Kalahari and the Australian outback until recently, networks forged by multilingualism, intermarriage, and friendship permitted plenty of opportunity for ideas to be spread and new skills passed among whole culture areas, not just contained within the local area where they originated. The size of the effective collective network of a deme matters in ensuring cultural fidelity and adaptive evolution over time. This has been demonstrated experimentally, in a paper by Maxime Derex, Marie-Pauline Beugin, Bernard Godelle & Michel Raymond. In 2013 they published "Experimental evidence for the influence of group size on cultural complexity” in Nature. They said “The remarkable ecological and demographic success of humanity is largely attributed to our capacity for cumulative culture"...and hypothesized that "perfect cultural transmission and innovations should be more frequent in a large population” and then used a computer game to show that cultural knowledge deteriorated less, and innovations occurred more often, in the kind of "cultural trait diversity” that larger populations could support. They also suggest that "in our evolutionary past, group-size reduction may have exposed human societies to significant risks, including societal collapse”.

Extensive individual networking represents an adaptation to reduce those risks. The data I collected among the Kua - in terms of individual networking - indicated a larger group size was created this way. Individual people had networks that only partially overlapped.

So, no band exists in isolation, it is just one temporary node in a tangle of hundreds of individual networks. This has significance for our understanding of the origins of cultural systems. Human cultures result from this kind of spatially extensive individual networking that interconnect hundreds, even thousands of people within a common field of circulating information. “Relatives” - kinship links - have long ceased to be the main or only basis for organizing residential groupings. My data indicated that “large group size” is independent of residential aggregations. It did not take sedentism or high localized population density to produce “cultural complexity”. It just takes a vast set of intersubjective connections - and these can be generated through extending individual information flows well beyond any limits imposed by mere genetic relationship. And we humans had that by (at least) the late Pleistocene.

Helga Vierich-Drever 29 January 2018 (18:49)

Pascal Boyer and Dan Sperber ask about how and why kinship loyalties can be extended to non-related individuals...

I assume here that since both of you are interested in the cognitive mechanisms involved when someone choses “sides” in a crisis, and why that choice is not always a straightforward alignment with people sharing the most genes.

Forgive me if I have mistaken the implication of your interesting questions.

What does it mean, for evolutionary models of our evolution, if we cannot fall back on the idea of competition between groups? This is especially critical to our understanding of cognitive evolution. It is widely asserted that humans are the product of gene-culture evolution: the feedback between two fundamentally different replicators, both heritable. And yet, it seems to me, little progress has been made exploring selection pressures generated on the biological replicator by the cultural one. Sure, people talk about how culture made it necessary for a larger brain to evolve, since language and complex tool making, cooking, clothing and shelter construction all, hypothetically, require more brain cells to be available. And sure, all these are obvious for understanding human cognitive systems.

Our genome steadily accumulates replication errors and mutations. As long as they are not too detrimental they can be carried along for eons; even a lethal variant can coast along indefinitely if it’s effect is at least somewhat masked by a morally functioning version: such are the evolutionary benefits of diploidy.

But how does the variability of information in each culture get generated? Internal creativity and imaginative tinkering are one source, of course. On of course it is obvious that variation - both good and not so good - can accumulate faster in a big population, just because there would be a greater number of creative geniuses and obsessive and quirky people who can’t leave well enough alone. But as I indicated in my remarks to Radu Umbres, I think the problem of generating sufficient variation of ideas, skills, and useful explanatory models for long term cultural adaptation was solved over 200,000 years ago. And that extension of individual networking well beyond genetic relatives was one of the solutions.

As attractive as kin selection and inclusive fitness models are for understanding why cognitive underpinning for altruism might have evolved, these models are insufficient explanations for much of human affiliative and intersubjective behaviour. Sure, we see a bit of light when we model games of tit for tat, ultimatums, snowdrift, and prisoner’s dilemma. We can even try to test hypotheses about how competition between groups might have been active in selection by eliminating genetic variants that did not form bonds of loyalty and develop “coalitions” in opposition to a competing “group”, as in the Tooby and Cosmides suggestion.

A few of these kinds of games and models have been undertaken cross culturally, but few have been tested against the actual observational data on foragers. Let me give this more thought and look up some of the case studies and see what I can do to explore this question.