The Smurf Studies: Do 7-month-olds have a

In a recent paper published in Science (24 December 2010) and entitled "The Social Sense: Susceptibility to Others' Beliefs in Human Infants and Adults", Agnes Kovacs, Ernő Téglás and Ansgar Denis Endress describe a striking set of experiments that may be of interest to ICCI readers, and suggest that "adults and 7-month-olds automatically encode others' beliefs, and that, surprisingly, others' beliefs have similar effects as the participants' own beliefs." These studies add to a growing empirical literature that started with Onishi & Baillargeon 2005 and that stands in contrast to Sally-Ann-style studies of false belief (which rely on explicit predictions and suggest it is not until 4 or 5 years that children can represent others' false beliefs). Here, the authors argue that representing an agent's beliefs -- even when they contradict one's own beliefs, and even when that agent has left the scene -- is triggered automatically and may be part of an innate human "social sense."

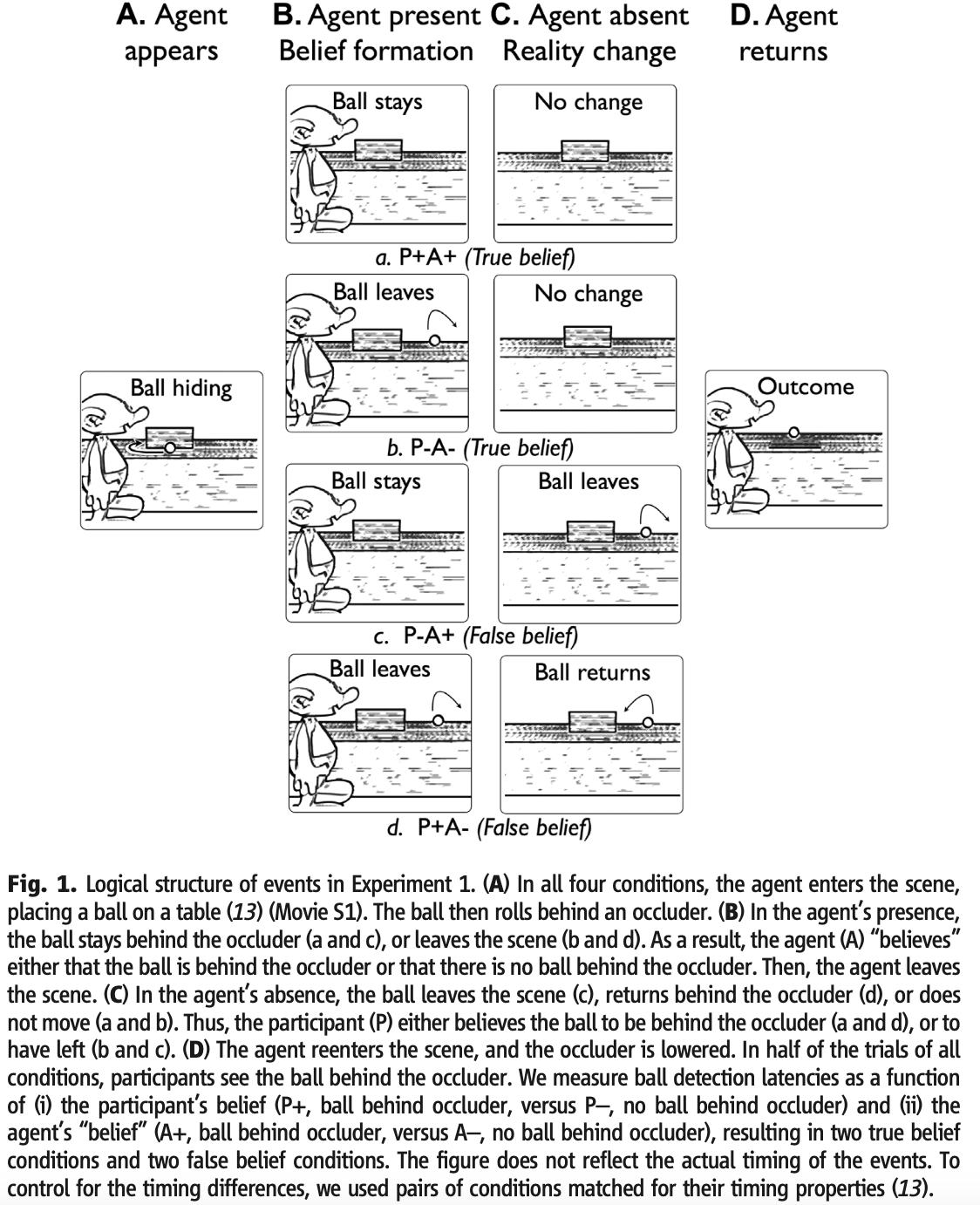

Around the Department of Cognitive Science at the CEU in Budapest, these are known as the "smurf studies", because they all feature a movie with different smurf dolls and a ball that rolls behind an occluder (Figure 1).

Kovacs et al, Figure 1

The main measure for adults is reaction time after the occluder is removed to detect whether a ball is present or absent. Adults are faster to detect the presence of a ball behind the occluder if they and the smurf both know that the ball should be there (true belief) AND are similarly quick even if they know the ball shouldn't be there, but the smurf would think it is there (false belief). To get at the question of whether this sort of automatic agent-belief representation is present early in life and thus possibly innate or at the very least pre-verbal, they tested 7 month olds in a looking time version of the adult experiments. Here they measure looking time to the "no ball" outcome, as an index of how surprised the infant is that the ball isn't there. The infant looks longer if the ball should have been there and is gone vs. the ball shouldn't be there, and it's gone (true belief). They ALSO look longer if they knew the ball shouldn't be there, but the smurf would think it IS there (false belief)! Hence both adults and infants are influenced in their expectations not only by their own beliefs but also by that of another agent, even if the agents beliefs are in contradiction with their own!

Aside from the relevancy of these results for theory of mind and social cognitive developmental research -- these studies also raise questions about the nature of mental representation and memory across delay. It's also a very meaty paper. There is a lot of data and a lot of ideas and hypotheses to sink our teeth into.

As Gyorgi would say, three cheers to Kovacs and colleagues for this exciting contribution to the social cognition literature. I only hope that they and others in the field will next address the crucial question of how it all happens!

Davie Yoon 3 January 2011 (21:47)

[b]How human-specific[/b] is the phenomenon described in this paper? What about other primates, or human-domesticated species, or other non-human-domesticated yet socially-complex species? Is the capacity for such mental representation [b]innate[/b]? Will we find the same pattern of behavior in newborn infants? What about dark-reared or otherwise visually naive animals? Does an individual's aptitude with this class of mental representations have important [b]consequences for other aspects of that individual's social life[/b]? For example, would the quality of these representations predict an individual's language learning trajectory, risk for social communicative disorders like autism, etc? How are [b]neural representations[/b] for unseen objects that do and do not match reality stored differently? How about one's own versus another's representation of such objects? Are the behavioral effects described in the paper consistent with an [b]advantage or interference[/b] effect? This would require comparing the current results with measures of adult RT and infant looking time to a baseline event in which no information about the presence of absence of the ball is provided prior to the inclusion event. Apologies to the authors if I have missed discussion of these issues that appear already in the manuscript or supplementary materials.