Do apes produce metonymies?

Your friend Olga is coming for a drink. You put two plates on the table, one with olives and the other with almonds. When both plates have been emptied, you ask Olga, “Do you want anything else?” “Yes, please!”, she answers, pointing to the plate where the almonds had been. What is she requesting? The empty plate? Of course not. She is requesting more almonds. To do so, she uses a gestural metonymy: pointing to a container to convey something about its (past) content.

Container-for-content metonymies are quite common in language use. Typical examples are: “I just had one glass” or “the school bus was singing.” Some of these gestural or verbal metonymies have become conventional but we can produce or understand novel ones without effort. What communicative abilities does it take to make use of metonymies? Could a 12-month-old child, who does not yet speak, spontaneously produce an appropriate gestural metonymy? For that matter, could an ape?

In his doctoral work at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Manuel Bohn asked an even more basic question: can infants and apes refer to absent entities? (See also earlier work by Liszkowski et al 2009; Lyn et al 2014). The capacity to do so is generally linked to the possession of language, so showing that they can would be an interesting challenge.

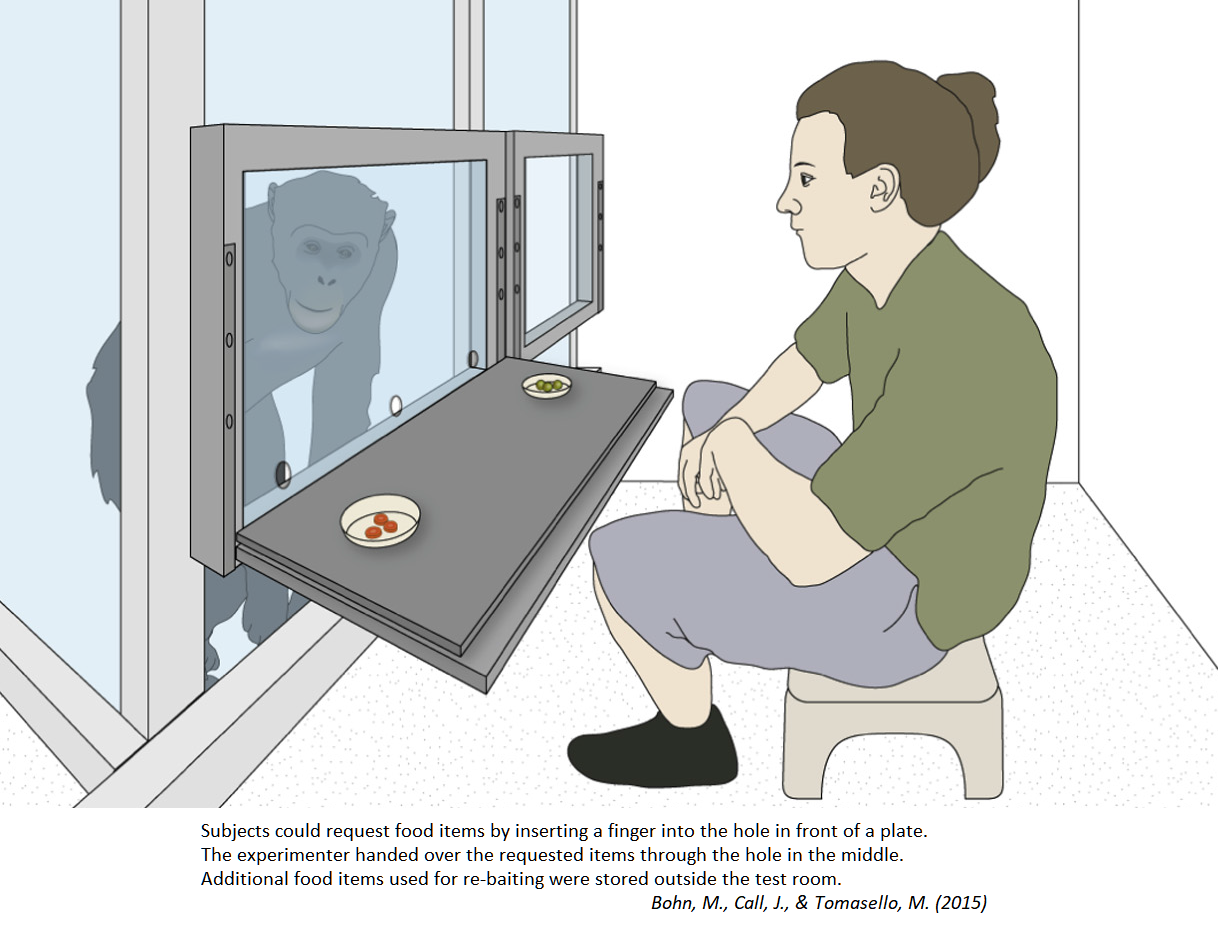

In one study (Bohn et al 2015), Bohn presented apes (chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans) with two plates each containing three pieces of food: grapes (a higher quality food for apes) on one plate, and pieces of carrot (a lower quality food) on the other plate. The apes could point to one or the other plate and would be given a piece of food from it. As soon as a plate was emptied, the experimenter would take it out of the room and bring it back refilled.

In the critical test trials, however, the experimenter let the plates go empty without refilling them. Would the apes point to a now empty plate (as your friend Olga did)? And if so, would they point indiscriminately to one or the other plate to request more food, or would they point to the plate that had contained their preferred food? Several apes did point to an empty plate, the one that had contained grapes. What were they trying to convey? Not that they wanted the empty plate, obviously, nor just, we assume, that they wanted more food, but that they wanted grapes. They were, in other terms, communicating about (or “referring to”) absent entities.

In a parallel study, Bohn presented 12-month-old children with objects of two kinds: wooden cubes on one plate and colourful balls on a second plate. A child could request objects of one kind or the other by pointing to the right plate. She would then be given the toy and could throw it in a container. Children had fun doing so, and more fun with the balls than with the cubes. Whereas in the training trials, the experimenter refilled every plate as soon as it was empty, in the test trials, he sat and waited. As the apes had done, children pointed to the empty plate that had contained their preferred items, the colourful balls. Again, they were communicating about absent entities.

This double demonstration – in itself an achievement – raises a major question: what kind of mental abilities make it possible for these apes and infants to try and request absent objects (grapes or balls) by pointing at a now empty plate? There is no simple and obvious answer to this question.

Take, to begin with, the somewhat simpler question: what mental capacities make it possible to point to an object that is present in plain sight in order to request it? A plausible answer (even if it isn’t that compelling) appeals to reinforcement. It doesn’t much matter how, in a given individual, this behaviour first occurs: it could be an effect of chance, imitation, or some inherited disposition. The behaviour becomes part of the individual’s repertoire through being rewarded again and again by third parties handing over the object pointed at. If this is how so-called imperative pointing works, then apes or children should expect that, if they point at an empty plate, they will be handed the plate (a pretty useless gesture, then, unless they do want the plate).

In older children and adults, pointing is clearly an ostensive gesture. It attracts attention not only to the item pointed at but also to the fact that the communicator intends, by producing the gesture, to communicate some relevant information (for instance that she wants to be given the item) and to make it part of the common ground.

Understanding ostensive communication involves bringing together the information directly provided by the communicative behaviour and a context of background information. This by itself, however, doesn’t determine a single possible interpretation, let alone the intended one. The key to comprehension is – or so Deirdre Wilson and I have argued – that every act of ostensive communication conveys a presumption of its own relevance. Assuming for instance that, by pointing, Olga intended to convey relevant information to you, you can infer that she intended to answer your question (“Do you want anything else?”) and, more precisely, to request more almonds. In this situation, this is the first interpretation that comes to your mind and that satisfies your expectation of relevance (for a more detailed account of how such inference works, read our Meaning and Relevance, 2012).

Comprehension of ostensive communication consists in attributing an informative intention to the communicator rather than in just decoding a signal. Comprehension, in other terms, is a special form of mindreading. Even though there is now good evidence of mindreading ability in great apes (notably Kano et al. 2017), it is far from obvious that they are able to engage in ostensive communication and in particular to produce and comprehend novel signals intended to give evidence of the communicator’s informative intention.

There is plenty of evidence, on the other hand, that infants do comprehend and produce ostensive behaviour. They not only point at a visible object; they also readily point to a container to refer to the object it contains, which is good evidence of expecting inferential comprehension (Behne et al 2012 – there is, by the way, limited evidence of comparable behaviour in apes, e.g. Robert et al. 2014). Still, it could be argued that when you point at a box to refer to the object it currently contains, you are also pointing in the direction of that very object. Some inference may be needed to decide whether you are referring to the container or to the item it contains, but at least the two possible referents are present, even if only one of them is visible.

This makes Bohn’s finding that not only infants but also apes point to an empty location to request an absent item quite remarkable: the behaviour of apes or infants pointing to an empty plate is neither an unambiguous signal nor an ambiguous signal with just two referents. So, what is it?

“It’s a metonymy!” semioticians might answer, and, yes, sure, a metonymy it is. But metonymy is not an explanation, it is something to be explained. In the case of linguistic communication, the classical view that the intended meaning is recovered by attending to relationships of proximity is as inadequate as the view that the intended meaning of metaphor is recovered by attending to relationships of resemblance. It is not that these explanations are totally false, it is that they fall so pathetically short. Any given item stands in a relationship of proximity (in time, space, role, etc) to so many other things, just as any given item stands in a relationship of resemblance to countless other items. Besides container-for-content, there are metonymies based on cause-for-effect, effect-for-cause, instrument-for-function, part-for-whole, whole-for-part, token-for-type (the last three being synecdoche, generally considered a kind of metonymy), and so on.

If being in a metonymic relationship was all that determined the interpretation of pointing to an empty plate, the pointing would be multiply ambiguous and could refer not only to the things the plate had just contained, but to about any object or action associated with that plate or with plates in general: knives, forks, cups, other food items, eating, dish washing; and in the particular case of the apes in Bohn’s experiment, it could refer not just to generic grapes but to the grapes that had already been eaten or to food in general, and not just to refilling the plate but to other actions such as taking the plate away. Of course, it seems quite clear that what the apes want is none of the above but just more grapes. Are we ready, however, to assume that they expect the experimenter to read their mind?

Bohn’s study provides, I believe, novel evidence confirming what we already had good reasons to believe, namely that infants are able not just to comprehend but also to produce ostensive gestures. We should be much more cautious in attributing the same competence to apes. Bohn’s study strongly suggests, however, that we should explore the possibility that, between the coded signals common in animal communication and the fully fledged ostensive communication typical of humans, there might be some intermediate form of partial ostension, exploiting the relevance aspect more than the mindreading aspect of ostension.

Let me explain. The first principle of relevance theory (what we call the “cognitive principle”: humans tends to maximise relevance in the way they allocate their attention and draw inferences) may well be true, even if to a lesser extent, of other animals with high cognitive capacities, apes in particular. If so, apes can expect the attention and inferences of their conspecifics to tend to maximise relevance. They may then be able and disposed to act on the mental states of others by attracting their attention to stimuli the relevance of which they can anticipate. Wildlife examples of such a disposition to act on the attention of others to produce predictable reactions include male chimps shaking branches to attract the attention of a female to their erect penis in the hope of mating with her (Tutin & McGinnis 1981). In Bohn’s experiment, the apes attracting attention to the empty plate may similarly anticipate that this will be relevant to the experimenter by suggesting to him to refill the plate, as he had done before.

Of course, acting on the attention of conspecifics (or of animals of other species) expecting a fixed behavioural response is quite common. What is involved here is less trivial; it is the ability to produce a novel behaviour and expect a novel response. The experimenter had the empty plate in front of him and was presumably aware of it. What the ape does is, so to speak, insist that this is more worthy of attention and more relevant than the experimenter seemed to be realising.

All this suggests a whole new direction of research on communication at the borderline of ostension, and not only among apes, but also among humans. Alongside fully fledged ostensive communication, humans may well engage in communicative behaviour aimed at enhancing the relevance of some stimuli without conveying much, if anything, about their mental states in doing so.

References

Behne, T., Liszkowski, U., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2012). Twelve-month-olds' comprehension and production of pointing. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 30, 359-375.

Bohn, M., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2015). Communication about absent entities in great apes and human infants. Cognition, 145, 63–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2015.08.009

Fumihiro Kano, Christopher Krupenye, Satoshi Hirata & Josep Call (2017) Eye tracking uncovered great apes' ability to anticipate that other individuals will act according to false beliefs, Communicative & Integrative Biology, 10:2, e1299836, DOI: 10.1080/19420889.2017.1299836

Liszkowski, U., Carpenter, M., & Tomasello, M. (2007). Pointing out new news, old news, and absent referents at 12 months of age. Developmental Science, 10(2), 1–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-7687.2006.00552.X.

Lyn, H., Russell, J. L., Leavens, D. A., Bard, K. A., Boysen, S. T., Schaeffer, J. A., & Hopkins, W. D. (2014). Apes communicate about absent and displaced objects: Methodology matters. Animal Cognition, 17(1), 85–94. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10071-013-0640-0.

Roberts, A.I. et al. (2014) Chimpanzees modify intentional gestures to coordinate a search for hidden food. Nat. Commun. 5:3088 doi: 10.1038/ncomms4088.

Tomasello, M. (2008). Origins of human communication. MIT Press.

Tutin, C. E., & McGinnis, P. R. (1981). Chimpanzee reproduction in the wild. Reproductive biology of the great apes: Comparative and biomedical perspectives, 239-264.

Wilson, D. & Sperber, D. (2012) Meaning and Relevance. Cambridge UP.

José-Luis Guijarro 10 July 2017 (19:46)

Do some pets also use metonymy?

Maybe I am totally mis-interpreting the behaviour of my small dog, Lolo.

When the water-recipient we have for him is empty, he goes near it, looks at us, barks, looks at the recipient, iteratively until we fill it up with water.

When he wishes to go out, he also goes near the place where its chain is hanging, and he indulges in the same sort of iterative behaviour: looking at us, barking, looking at the hanging chain, as long as he needs for us to agree to take him out.

Manuel Bohn 11 July 2017 (09:48)

Social aspects of "ape metonymies"

Thank you very much, Dan, for choosing to blog about my work, I feel very honored!

I really like the idea of exploring something like a „middle ground“ between coded animal communication and full blown human ostensive communication. We ran a little follow-up study with apes to the one you discussed here (http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/com/130/4/351/ - PDF) that might be of interest.

In this study, we used the same setup that was described above but this time we varied the social aspects of the situation, namely the experimenter’s competence to provide food and/or her knowledge about the previous content of the empty plate. The experimenter’s competence was established during interactions prior to the experiment in which the experimenter provided food (of all sorts) to the subject (or not), the experimenter’s knowledge depended on whether she had previously seen the content of the now empty plate (or not). The logic was that apes should only point to the empty plate if a) the experimenter is able to provide more food and b) knows what the plate previously contained. In the experiment we crossed these two factors and found that apes take both of them into account when choosing whether to point to the empty plate or not, with competence being slightly more important than knowledge.

What this suggests is that apes have some understanding of the potential ambiguity of the point to the empty plate and that they are aware that it takes some kind of previous interactions (common ground) for the gesture to be relevant. In Dan’s words, apes expected a novel response from the experimenter with an understanding that their are certain interactional preconditions for the response to be produced. The fact that the experimenter’s knowledge was less important for apes supports Dan’s suggestion that the mind reading part of full fledged ostensive communication might be less pronounced. In an ongoing study with 12-month-old infants, we are currently testing whether they take into account the experimenter’s knowledge.

Best,

Manuel

Reference:

Bohn, M., Call, J., & Tomasello, M. (2016). The role of past interactions in great apes' communication about absent entities. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 130(4), 351-357.

Dan Sperber 12 July 2017 (01:12)

Does Lolo use metonymy?

Thanks, Jose-Luis, for your observations. Dogs do indeed have remarkable communication skills – well documented in much recent experimental literature – which have evolved, in the process of domestication, beyond the already notable skills of wolves. The two behaviours of your dog Lolo you mention are, in this respect, typical. Do they, however, rely on some grasp of metonymic relationships? The apes and the infants’ communicative behaviour in Bohn’s studies involve the production of a novel appropriate behaviour for a novel goal, which justify tentatively considering that they may have some understanding of how to influence a cooperative agent in a novel situation. Lolo’s behaviour, on the other hand, occurs again and again in the same situation and with the same agents. It might, for all we know, have been progressively learned and fine-tuned through fairly standard reinforcement. You might be endowing it with a much richer meaning than Lolo does. To investigate whether his competence involves some degree of comprehension – which, I do not deny, may well be the case – more and different kind of evidence would be necessary.

José-Luis Guijarro 12 July 2017 (16:57)

Novel behaviour becoming automatic?

Thanks, Dan! Just one question: I agree that this behaviour seems fully automatic now. But he started it himself without any coaching whatsoever, first with the hanging chain, and THEN, some time after that, with the empty recipient. Both first instances do seem to me to have a clear component of your "...production of a novel appropriate behaviour for a novel goal, which justify tentatively considering that they may have some understanding of how to influence a cooperative agent in a novel situation".

Dan Sperber 12 July 2017 (23:25)

Is common ground truly necessary?

The second study that Manuel is invoking in his comment is indeed quite interesting (and it is likely to become even more so when we have the infant data to compare it with). It is unclear however what form of mindreading it reveals, if any. Pointings to the plate that had contained grapes were more frequent when the experimenter was the one who had brought grapes to the ape on a previous occasion. These pointings, moreover, were even more frequent when this competent experimenter had been there in the warming up phase of the experiment and had seen that there had been grapes on the now empty plate. Manuel and his co-authors distinguish having brought grapes before as evidence of “competence” in the eyes of the apes and having seen grapes on the empty plate as evidence of “knowledge,” but I do not find this distinction that compelling. Knowing what had been on the empty plate is as much an element of the competence needed to understand what food to bring as is knowing where to get the food. Someone reluctant to attribute mindreading to apes – not me! – might argue that what the apes attribute in such conditions (with greater confidence when both conditions are fulfilled) is a behavioural disposition rather than a contentful mental state.

Even assuming, as I am happy to do, that this study provides some evidence of mindreading, does it follow that it speaks to the issue of “common ground” (what in relevance theory we called “a mutual cognitive environment," but, while I stick to our analysis of what is involved, I have no problem adopting the more common idiom “common ground”)? What is involved this time, is not just that the ape should know that the experimenter has the knowledge needed to refill the plate as requested, but also that experimenter should know that the apes knows this, and so forth. Why should the ape care? Is common ground necessary to expect the experimenter to understand the pointing? I don’t see why (and Deirdre and I have argued that common ground is not a precondition of comprehension in such cases).

In any case, it would not be hard to test whether the ape (or a human participant in a similar experiment for that matter) who is pointing at an empty plate relies on common ground in expecting to be given items of the kind that had been on that plate before. One could, for instance compare two conditions where participant A first observes an interaction between the experimenter and another participant B. The experimenter refills a plate of grapes for B. B leaves after having requested and eaten all the grapes. Now A takes the place of B: will it point to the empty plate in the hope of that the experimenter will refill it again with grapes? In one condition (“common ground” condition), A was a visible witness of the interaction between B and the experimenter. In the other condition (“no common ground” condition), A saw everything but could not be seen by the experimenter. Would participants point more to the empty plate in the “common ground” than in the “no common ground” condition? I am not sure (but I would be curious to find out).

Dan Sperber 13 July 2017 (16:19)

To Jose-Luis, about Lolo

Yes, Jose-Luis, it is quite possible that your dog Lolo came up with the two communicative behaviours you mentioned on the basis of some degree of comprehension of the effects they might have on you. But we don’t know that it is so when it is also possible that he developed these behaviours through reinforcement (standing next to the water recipient tended to be rewarded with water; standing there and barking increased the probability of reward, as did looking at you in the process, and so on). We would need solid experimental evidence (or at least the recordings of a webcam next to his water recipient from the time when he didn’t communicate in this way to the time he did) to feel more confident that you are right.

Manuel Bohn 16 July 2017 (14:22)

A "middle" ground

The study Dan is suggesting is sounds very interesting indeed. My prediction would be that apes would not differentiate between them. However, I would also predict that 12-month-old infants would not. My reasons for this are the following: In a series of studies, Henrike Moll and colleagues showed that direct social interaction around an object is necessary for young infants to assume that their communicative partner knows about it. Merely observing third party interactions was not sufficient (e.g. Moll & Tomasello, 2007). What about apes? Directly comparable studies have not been conducted so far. However, the two manipulations in our study ("knowledge" and "competence") could also be distinguished in terms of the length and intensity of the social interaction around the plate and its content(s), with "competence" being more intense than "knowledge". Our results suggest that the more prior interaction, the more likely apes are to assume that their point to the empty plate will yield food. Why is direct social interaction so important? What it does, I think, is give the communicative partners good reasons to assume that the respective other will continue to treat the plate in line with the focus of the previous interaction (requesting and giving food). It determines how the plate is relevant. This mutual expectation could be seen as something like a "middle ground", devoid of mind reading, which could even serve as a developmental starting point (phylo- and/or ontogenetically) for full blown common ground involving recursive mind-reading

References:

Moll, H., & Tomasello, M. (2007). How 14-and 18-month-olds know what others have experienced. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 309-317.