Mèng Zǐ (372 – 289 BCE) on the moral organ

This post is part of a series on the ‘history of social sciences’.

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

So far, in this mini-series on the (possibility of a) history of social sciences, I have only discussed the work of a philosopher that is relatively close to us, in terms of space and time. However, I believe that the same story can be told for far more distant philosophers.

Consider, again, the idea of a moral module, advocated by contemporary psychologists. Elsewhere, I have argued that this idea is not totally new and that Scottish philosophers had come up with a similar idea in response to a similar problem (how to account for our innate, universal, unconscious and specific thoughts about right and wrong?) But this idea of a moral organ can be found much earlier, on another continent, Asia, during a different era, the third century before CE, in the work of Mèng Zǐ, usually known in the West as Mencius.

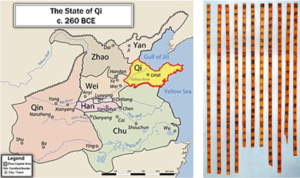

Mèng Zǐ was a Chinese philosopher who was arguably the most famous Confucian after Confucius himself. Supposedly, he was a pupil of Confucius’s grandson, Zisi. Like Confucius, according to legend, he travelled China for forty years offering advice to rulers for reform. During the Warring States Period from 319 to 312 BCE, Mencius served as an official and scholar at the Jixia Academy in the State of Qi, probably the first State-founded academic institution in human history, along with the library of Alexandria. Disappointed at his failure to effect changes in the world of his time, he retired from public life.

Picture: The State of Qi where Mencius worked for some time and

Picture: The State of Qi where Mencius worked for some time and

the Guodian Chu Slips written in the 3rd century BC

You may think that by attributing the idea of a moral organ to someone who lived in such a different mental universe, I am going much too far in my reconstructive enterprise. But hold on for a second. Mèng Zǐ was actually interested by the same questions as contemporary scientists: Are humans moral? Are they good by nature? Do they respect moral principles for genuine moral reasons? He noticed, for instance, that our moral actions cannot be reduced to a taste for reputation:

“If people witness a child about to fall down a well, they would experience a feeling of fear and sorrow instantaneously without an exception. This feeling is generated not because they want to gain friendship with the child’s parents, nor because they look for the praise of their neighbors and friends, nor because they don’t like to hear the child’s scream of seeking help.”

So Mèng Zǐ acknowledged that we sometimes do things to make friends or to look good, but he argues that there are also genuinely good actions, without ulterior motives. You might reply that such an argument does not prove that Mèng Zǐ defend the idea that we have a moral organ. But there’s more for Mèng Zǐ goes on to say:

“Therefore, it can be suggested that a person without a mind of commiseration is not human, that a person without a mind of mortification is not human, that a person without a mind of conciliation is not human, and that a person without a mind of discernment is not human. The mind of commiseration is the driving force of benevolence. The mind of mortification is the driving force of righteousness. The mind of conciliation is the driving force of propriety. The mind of discernment is the driving force of wisdom. A person has these four driving forces, just the same as he has four limbs.”

Whatever the translation problems, the comparison between commiseration and limbs is explicit enough to conclude that Mèng Zǐ did think that morality was natural. And Mèng Zǐ goes further by comparing our moral organ not only with physical organs but also with sensory organs. Indeed, he says that the whole world agree with I-ya (an ancient chef) with regard to flavor, Shih-k’uang (an ancient musician) with regard to music and that Tzu-tu (an ancient handsome man) is handsome. He concludes:

“Therefore I say there is a common taste for flavor in our mouths, a common sense for sound in our ears, and a common sense for beauty in our eyes. Can it be that it is in our minds alone we are not alike? What is it that we have in common in our minds? It is the sense of principles and righteousness (i-li, moral principles). The sage is the first to possess what is common in our minds. Therefore moral principles please our minds as beef and mutton and pork please our mouths.”

Picture: The moral brain according to Greene and Haidt

Picture: The moral brain according to Greene and Haidt

Even at the time of Mèng Zǐ, sensory organs were both clearly mental (in the sense that they cannot be easily reduced to physical components) and clearly material (they were aware that vision comes from the eyes and taste from the mouth). In other words, it seems justified to describe Mèng Zǐ’s ideas of the basis of morality in term of a ‘moral module’ just as historians of Chinese science talks about magnetism, algebra or geocentric models when they study Chinese physicists, mathematicians or astronomers.

Of course, I am well aware that Mèng Zǐ lived in a very different social world than ours. For instance, at his time, the debate about morality was essentially normative. But I think that 1) the contemporary debate also has very interesting normative aspects and that’s probably what makes it so exciting and 2) the observations that led Mèng Zǐ to his conclusion (the existence of genuine moral acts, the common taste for morality, etc.) are not alien to contemporary philosophers, psychologists, and anthropologists (think about homo economicus or cultural relativism).

Now that we’ve seen the links between Chinese concepts and today’s question, we can move on to other interesting questions: if Chinese philosophers/anthropologists/psychologists (pick your choice) were at least as good as Western ones during antiquity, what prevented them from going further? Is it related to chinese metaphysics, as Joseph Needham famously argued? Is it an effect of the chinese writen system, as Toby E. Huff [1] suggested? Is it a lack of geographical barriers and political diversity, as Jared Diamond seems to think? Is it that the substantial resources taken from the New World to Europe made the crucial difference [2] between European and Chinese development? I guess this too big of a question for just a week…

[1] Huff, T. E. (2017). The rise of early modern science: Islam, China, and the West. Cambridge University Press. [2] Pomeranz, K. (2000). The great divergence: China, Europe, and the making of the modern world economy. Princeton University Press.

2 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Nicolas Baumard 28 June 2011 (18:50)

For those interested by the topic, Jeremy Lent at [url=http://liology.wordpress.com/Finding the Li]Finding the Li[/url] discusses Chinese analysis of morality in his [url=http://liology.wordpress.com/2010/05/05/chinas-greatest-gift-to-the-world-its-philosophy/]review[/url]of “A Chinese Ethics for the New Century” by Donald Munro.

Emmanuel Lazinier 7 January 2012 (20:08)

Those who can read French might be interested in an essay I wrote in 1992 “La morale “positive” d’Auguste Comte à l’épreuve de la science… et de la Chine” (http://membres.multimania.fr/clotilde/morale.xml), where I paralleled Mengzi “xing ben shan” (“humain nature good at root”), Auguste Comte’s altruism, and modern efforts by neuroscientists to establish the natural bases of ethics.