Quiet online spaces as a form of mutualistic nudging for our hyper-networked world

On April 26, 2020, the Guardian published an article entitled “As isolation stress sets in, many find that sharing quiet online spaces is the key to boosting brain power.” It began,

“There are Zooms for pub quizzes, Zooms for dinner parties, Zooms for work meetings and now there is a Zoom for sitting together and not talking at all. Behold, the silent Zoom! On paper, the practice of logging on to a video-conferencing site to sit with strangers for an hour without communicating may hold limited appeal. In practice, silent Zooms have become a lifeline in lockdown for users trying to focus on writing, reading, meditation and more.”

The next day, inspired by this article, a few of us launched an “Online silent workspace for mutual moral support,” started testing it, and found it quite useful in these days of Covid-19 confinement. Most of us now feel that it would be nice to have such a virtual workspace available permanently. I write this to present the idea, share a bit of what we have learned from our two-week experience, and to reflect on what it would take for this to become a regular cultural practice.

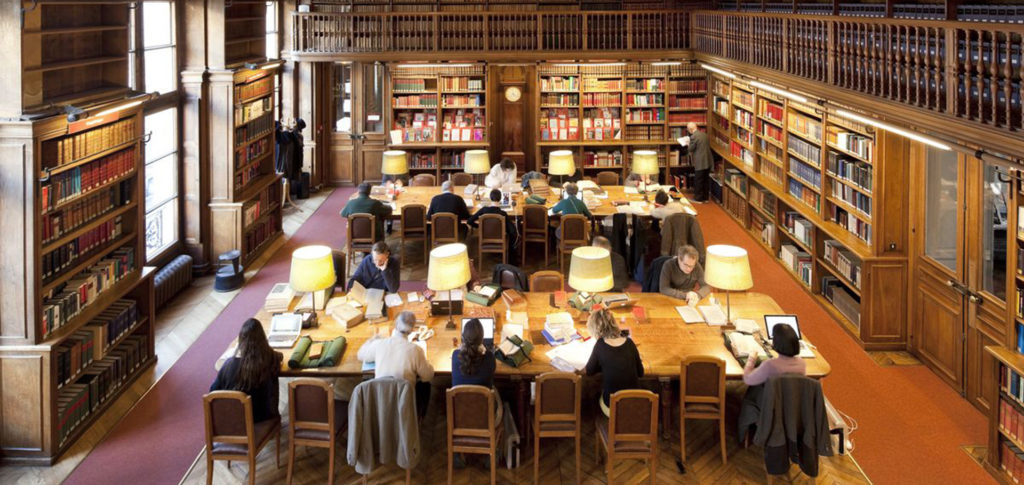

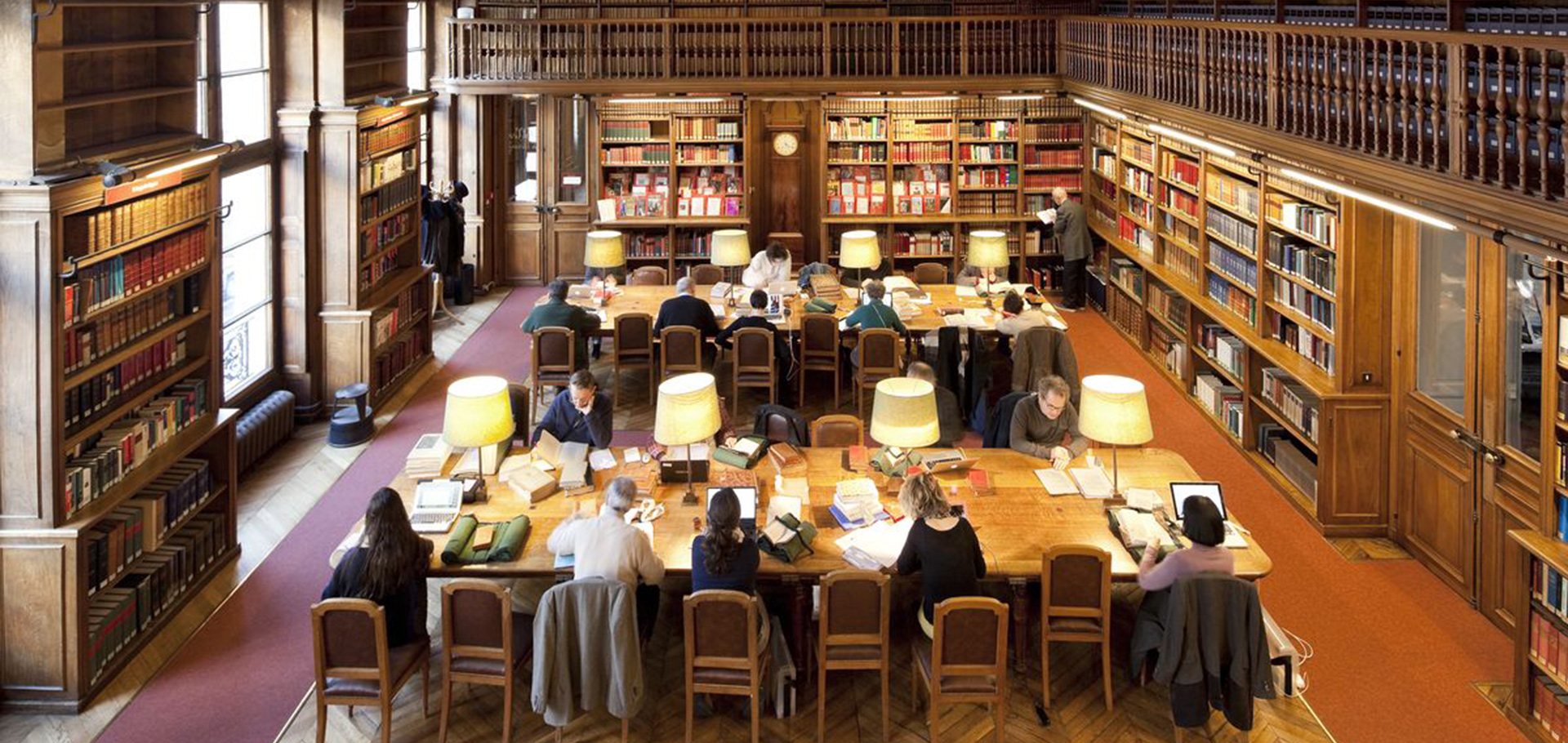

Many people find they work better in a library even when they don’t need to borrow any book, the presence of other people working quietly around them being somehow supportive. Much of what makes a library a good place to work, even when you don’t need anything from its shelves, can be replicated online and that is what we did.

Using Zoom, we opened everyday for 10 hours a workspace that participants could join whenever they wanted and for as long as they wanted, with the following rules:

– Video but no sound connection. If you want to communicate with another participant, do so via other means (phone, skype, …)

– Join when you want to work. Better turn off your video for longish work interruptions (e.g. lunch break). Leave the meeting when you stop working for good. You are always welcome to return.

– It is ok to listen to music, answer phone calls or skype, and so on: since the sound is off, it doesn’t disturb others.

When you link to the workspace, you see a window divided in as many smaller windows as there are participants online. You can put the reduced workspace window in a corner of your computer screen, you may open a full-size workspace window and keep it partly or fully occluded by other windows and look at it when you want (as you might, in a library, work with your back to the room and turn around when you feel like it), or you might login to the workspace from another device such as a tablet and place it sideways (and, if you want, dim its light) so that it does not distract you.

The presence of other people working might be less empowering on a screen than in a library reading room, but the virtual workspace, we found, has some unique advantages too. In particular, you don’t have to leave home; you don’t have to worry about making noises that might disturb others; you can return to it as often as you want in no time. There was no direct interaction among us, except for some occasional handwaving to a newcomer, and that didn’t feel particularly disturbing or awkward.

The number of people simultaneously online in our workspace these two weeks has varied between 2 late at night and 8 in the middle of the afternoon (the number of people who were invited to join went from 3 on the first day to 15 today). A few, came, looked, and went, but most of us have become hooked.

The worspace had to be managed by one of us: reopening a Zoom meeting every day for instance. Although it was quite easy to do so, especially in this time of confinement, it is dubious that such a workspace would keep going in the long run, unless it became permanent and basically automatic. Such workspace should at all times be available and open to all the members of the group (which should be of a size such that, at most hours, one could be confident not to be alone in the workspace (at least, not for long), and so that the workspace would not become overcrowded either.

An alternative would be to have a silent worspace offered (for free or for a cheap subscription) to all around the planet, with the benefit, when joining, of always finding people to work with and the disadvantage of anonymity. Of course, both forms (group vs open worspace) and other forms too may well be developed in parallel or in conjunction.

We have started investigating ways to develop or acquire such a permanent silent workspace for our group, piggybacking on an existing service, as we have been doing, or otherwise. What we need is something minimal, much simpler than all current offering for online meetings, webinar, co-working, and so on. No sound, no chat, no presentations, no sharing of documents, no joint projects, no emojis, no likes, no geolocation, no coaching, no bells and whistles. Just visual copresence of people working each on their own.

I assume that we are not the only ones who have worked together in this way (even if it was disappointing not to find useful models, links, or advice in the Guardian article). It would be nice to share experiences and ideas about how to go forward. I write this post in the hope of getting comments, suggestions, and even practical offers.

There is also food for thought in this kind of experience. Why and how does it work? Why does working in a library (or, for many, in a café) work? Is this a form of nudging that is mutualistic rather than paternalistic? If so, how relevant might mutualistic nudging turn out to be in a hyper-networked world where both cultural epidemiology and old fashioned medical epidemiology meet novel challenges?

3 Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Ophelia Deroy 13 May 2020 (21:18)

How to make mutualistic nudges fly (online) ?

It is a sweet idea ! Being allergic to Zoom by now, I may still give it a try 🙂 But, Dan, what is a mutualistic nudge? Seems that your workspace changes one’s pay-off structure (works better than alone).And how could one guarantee that this type of category really becomes like a public space, and does not work by conformism or felt obligation (my group/these people do/es it, I have to join)? This, in my experience, is very much the case for many distant online meetings, where even the ‘feel free to join’ creates a series of mild obligations.

Dan Sperber 13 May 2020 (21:39)

Ophelia’s questions

Here are some answers:

On conformism. The kind of virtual silent workspace I suggested is no more a source of external pressure than a public library, a gym, or a swimming pool. What you do there is for your own benefit and does not depend on what others do and on whether they succeed or fail, or rather, it may be hampered by obnoxious behaviour, which, in such places is relatively rare and, in a silent virtual space, is moreover harder to produce and easier to block.

On felt obligation. You might go to the library or the gym because you feel you ought to work or to work out, but the external institution helps you do what you feel you should do and might make it easier hence more probable, but it doesn’t put pressure on you. A virtual workspace even less so. Unlike what happens in an online collaborative meeting, there is no pressure to attend. You are not “joining others.” For those who feel pressure just from being in the presence of people who recognize them, I suggested the individual subscription plan where you end up working in a virtual space with people who don’t know you and whom you don’t know.

On pay-off structure and nudge. An interesting question that I am not sure how to answer. Unless you take as axiomatic that the only way behaviour can be altered is by altering the agent’s expected utilities, it is not that clear that the best description of the way a nudge works must in all case boil down to showing how it changes the pay-off structure. In many cases – and, I would argue true or at least prototypical nudges are good examples of this – it is also possible to explain changes in behaviour by changes in saliency structure. The fly in men’s urinal (the archetypical nudge) draws the agent attention and this may trigger what, in this case, is likely to be a quasi-reflex evolved behavioural response that influences behaviour even in the absence of expectation of a higher pay-off. Same thing with nudging people to do x by informing them that most of their neighbours do x. These are examples of paternalistic nudge. In the kind mutualistic nudge provided by a virtual workspace, seeing other work may just render more salient this activity, making more probable that you engage in it yourself and that, in so doing, you reinforce the nudge for others. Of course, this can be reframed in expected utility terms, but why rush doing so when we still know so little?

Hal Morris 3 June 2020 (02:45)

What’s a little paternalism among friends?

I like “mutualistic nudging”, and think it is a very interesting edge case of the normal human attraction to doing things with other people. At least you don’t shoot yourself in the foot with your phrase-making as Cass Sunstein seems compelled to do with phrases like “paternalistic libertarianism” and when searching for what to call a sensible way to discourage false rumors, he comes up with “chilling effect.”

So when he co-authors a book called “Nudge” people are going to say he’s the guy who came up with paternalistic libertarianism and wants to put a “chilling effect” on free speech, so “nudge” becomes another meme for scaring libertarian-tending people on the “right”. Likewise Alvin Goldman floated the phrase epistemological paternalism. Is there a university course called Anti-Rhetoric, which teaches you to do the opposite of the rhetorically winning move?